The fact that Graham Norton voices a hippie called Moonwind who twirls signs on a Manhattan street corner is just one of the surreal, “Sorry, what now?” elements of Pixar’s latest. An ever-changing genre mish-mash, it’s an unpredictable box of curveballs, mixing its slapstick and sentimentality with big ideas. Generally there are two types of Pixar films – the ones that are really for the kids, and then the ones for all of us, the ones that plug away at more philosophical concerns. Early on, a character here straight-up explains something about “all quantised themes of the universe.” Nobody said that in Cars 3.

When Joe (Foxx), a jazzer from Queens, New York, who’s never quite made it tries out as a pianist for legendary singer/band-leader Dorothea Williams (Angela Bassett) and impresses her, he’s so beside himself with joy he doesn’t even see the manhole he plunges into. As it turns out though, he’s not quite dead. Escaping the imminent crossover into The Great Beyond he instead escapes into The Great Before, a celestial nirvana where unborn souls which look like little baby ghosts are assigned personalities. There, mentors are assigned to souls that need a little help to give them the impetus they need to truly live. Joe finds himself lumbered with soul 22 (Tina Fey), who just wants to stay where she is. In a Christmas Carol-tinged sequence where she accompanies Joe to survey his former existence, he concludes that his life was meaningless. And there the existentialism ratchets up a notch, or ten.

Monsters, Inc, director Pete Docter’s first feature, was another such meeting of the real world and the fantastical, with the latter rendered with a similarly bureaucratic business-like approach. Just as he did in Inside Out, Docter – accompanied this time by co-director Kemp Powers – delights in the mechanics of how an imagined system might actually work, and once again it’s a wry exploration – it makes perfect sense to have Richard Ayoade voicing one of the number crunching ‘counsellors’ here – with sardonic asides all round. “You can’t crush a soul here, that’s what life on Earth is for," says 22. Another one of The Great Before’s denizens calls a human’s body a “meat suit”.

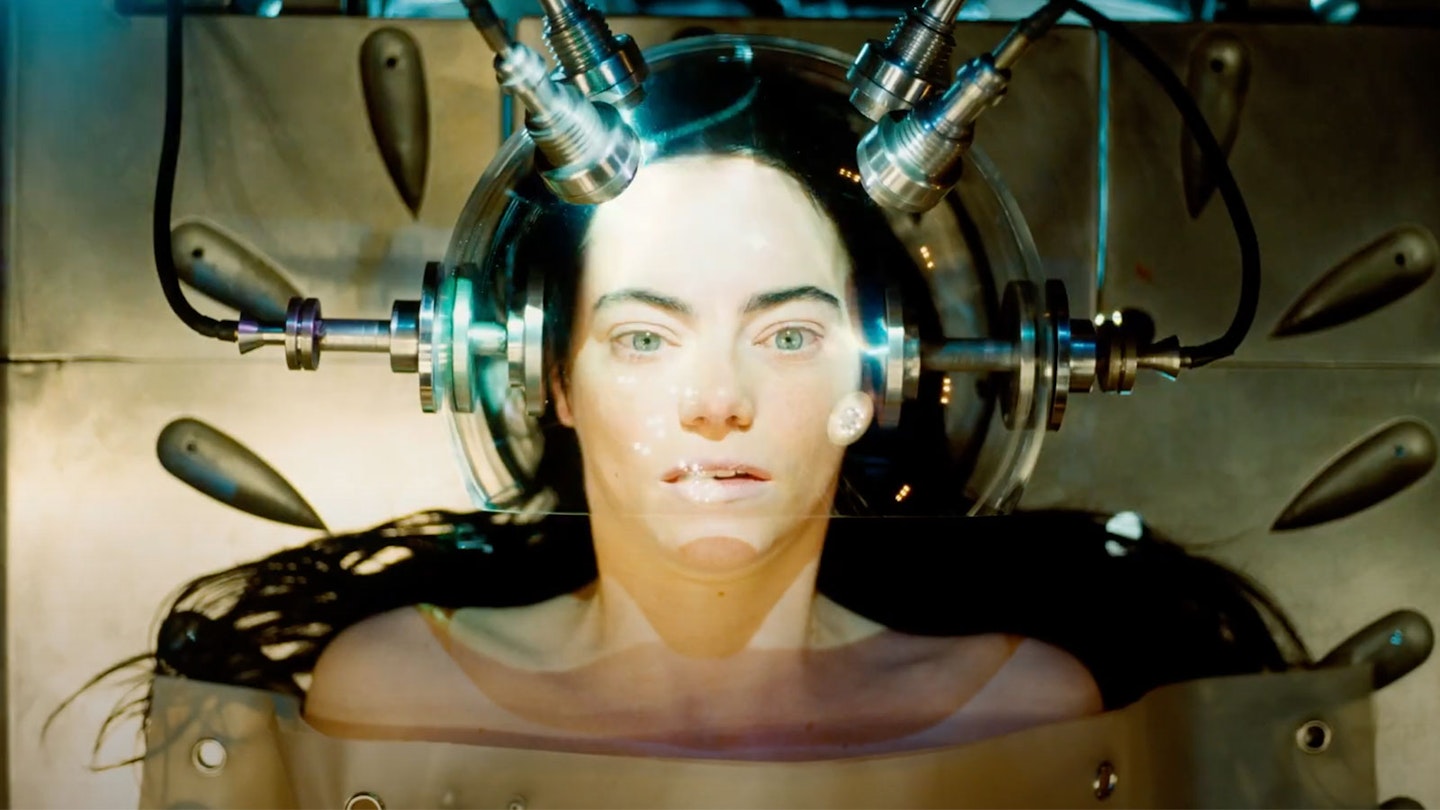

The counsellors resemble glow-in-the-dark Picasso drawings, used to clever effect, especially when one of them arrives in New York, ingeniously camouflaging himself in a subway station. The human character design is even more wonderful, full of so much nuanced personality they tell stories in an instant. Soul might be Pixar’s most exquisitely lit film – cinematographers Matt Aspbury and Ian Megibben fill both worlds with textures to die for. This New York is just a notch away from reality, and so authentically, lovingly executed, you can feel it. It’s all gloriously lived-in, which is fitting for a film that’s an ode to life.

For all its vision, though, it’s a little Pixar-lite. It’s a gorgeous 100 minutes, but not a huge emotional journey. The stakes seem strangely low, all things considered, without the big weepy gut punches you might hope for, certainly of the potency that Docter’s unleashed in Up and Inside Out. Despite an overriding theme that’s set up from the start, the different worlds don’t quite gel – Joe and 22 team up, but their partnership jars, and at times it feels like three films in one, which makes for some tonal zig-zags. For such big ideas, it’s surprisingly slight.

Still, it’s rewarding. The scenes between Joe and Dorothea are so spirited, as are the moments with him and his mother (Phylicia Rashad). This is the first Pixar film with a black character as the lead, and African-American co-director Powers’ influence permeates it all: it is so richly realised, so keenly felt. The filmmakers took notes from African-American cinematographer Bradford Young (Arrival, Selma, When They See Us), and these faces look – genuinely – stunning.

It’s the detail that hits home. There are some transcendental moments in this film, moments where the narrative so perfectly hits the animation, and you get swept away in it. There’s a place in The Great Before called The Zone, a window into the moments when we lose ourselves in what we’re doing, and at its best Soul itself makes you feel similar. Joe having a revelatory moment on a train, the subway tunnel lights blinking behind him as the train shoots through. Hazy neon through a steamy window. This is the Pixar magic. And in those moments, everything makes sense.