With two of his first five features being resounding box-office failures, another being so badly cut by the censors that it was unshowable and another still simply being abandoned on its completion, Claude Lelouch can be forgiven for taking so many easy options with Un Homme et une Femme. In many ways, he deserved his commercial success, as he shrewdly identified a gap in the market - a subtitled film which didn't intimidate those reared on mainstream mediocrity. But the critics castigated him all the way to the bank. He may have landed the Palme d'Or at Cannes and the Oscar for Best Foreign Film, but as far as the nouvelle vague bible, Cahiers du Cinéma, was concerned the movie didn't contain `a centimeter of celluloid' worth screening.

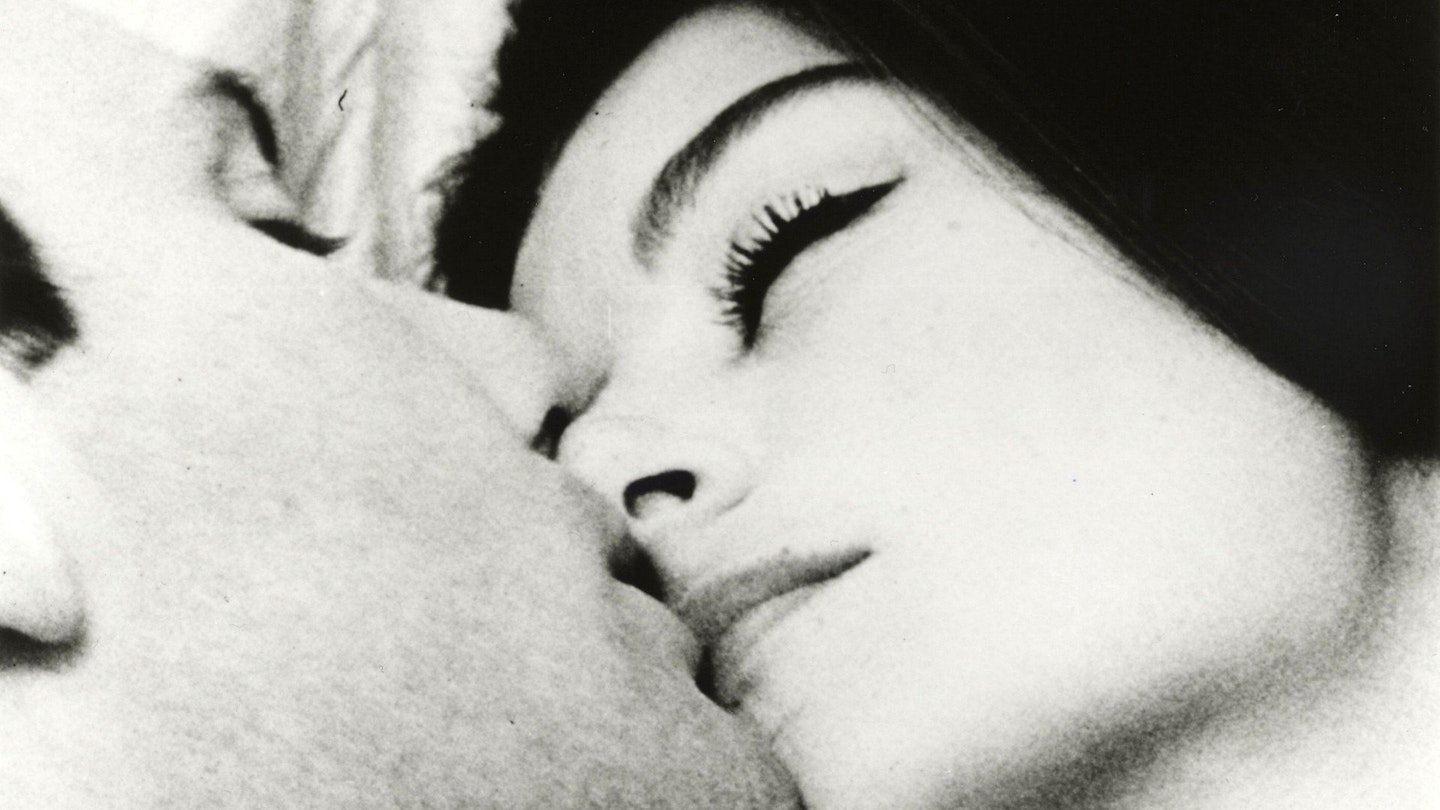

Ironically, this is very much a work in the auteur tradition, as not only did Lelouch produce and direct the picture, but he also photographed and co-edited it and jointly penned the Oscar-winning screenplay with Pierre Uytterhoeven (from his own story). Indeed, Lelouch did such a good job of imposing his own personality on proceedings that Jean-Louis Trintignant and Anouk Aimée simply had to turn up and look photogenic (although Trintignant did have to handle a couple of interior monologues) against the glamorous backdrops.

However, in his earnestness to replicate the energetic camerawork and editorial audacity of his contemporaries, Lelouch too often came across as an homagist rather than an artist with a singular vision. His close-ups were calculating to the point of winsomeness, while his modish celebration of such chic careers as cinema and motor racing produced images more suitable for a commercial than a feature. He later protested that the story questioned this sort of cultural transience by insisting that the film was about the legacy that the dead leave in the hearts of the living. But the majority of people who flocked to see it in the mid-60s were much more interested in its glossy romanticism and Francis Lai's catchy score.

A best-forgotten sequel, Un Homme et une Femme: Vingt Ans Déja, emerged to much derision in 1986.