The film work of David Mamet has always divided audiences, with some spectators thoroughly irritated by the labyrinthine plotting, staccato dialogue and lack of obvious cinematic 'flourish'. Indeed, the films are often dismissed as stage plays somewhat unimaginatively transferred to the big screen. House Of Games, the writer's directorial debut, contains all the ingredients that annoy his critics. The dialogue is arch, the acting style self-conscious, and Mamet revels in his usual enthusiastically inventive use of barrack-room language ("Where am I from? The United States Of Kiss My Ass.").

It's unlikely to convert anyone, but for fans, it's a pure delight. Mamet's plot revolves around psychiatrist Margaret Ford's (Lindsay Crouse) attempt to study a working con-artist, Mike (Joe Mantegna), and her descent into a barely penetrable web of con and counter-con. It's a story that resembles an extended game of Find The Lady, with Mamet as street-corner huckster. Time after time he seems to reveal to the audience what's actually going on, only to turn the card and hornswoggle us out of the truth yet again.

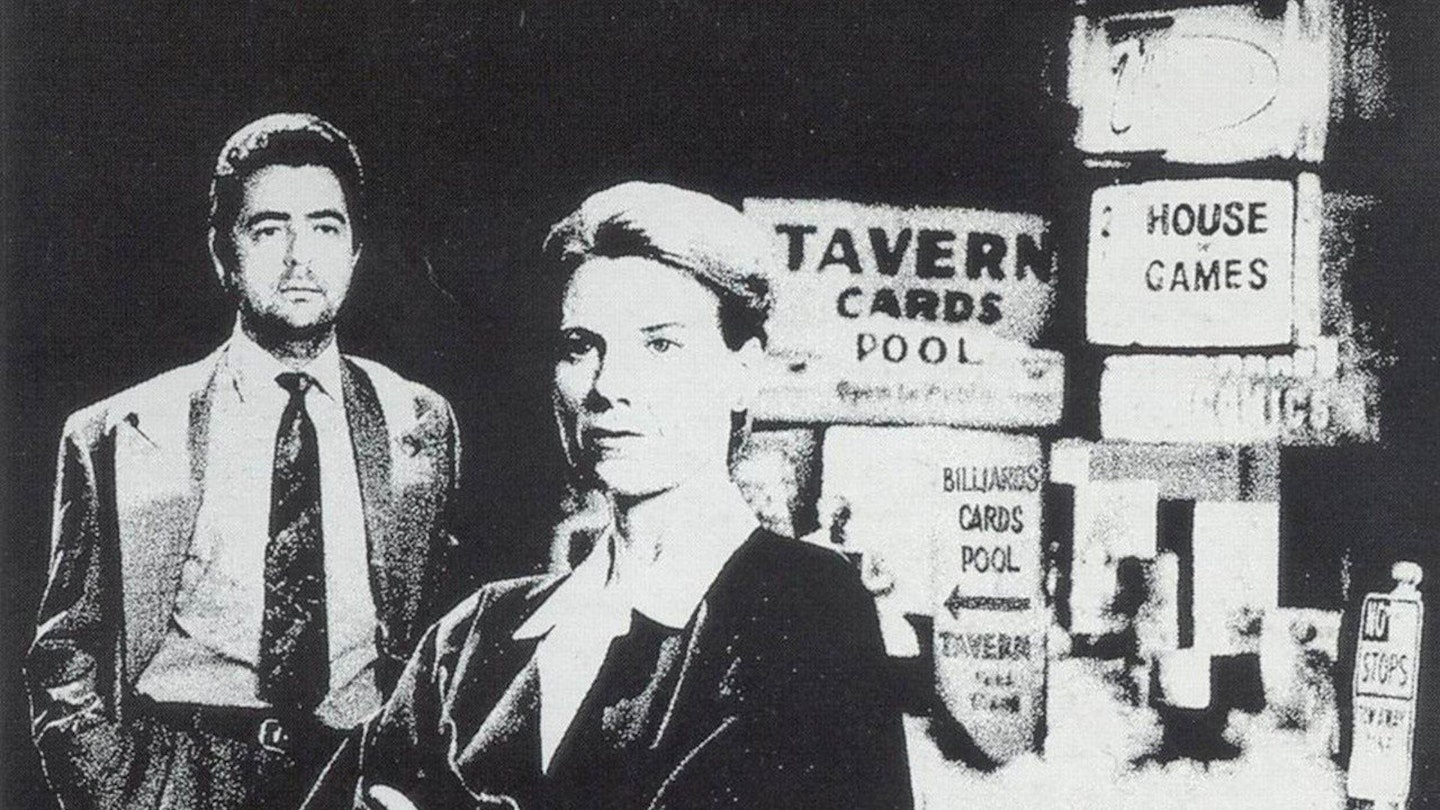

As to Mamet's often criticised, restrained style, the debut director may not be in the Scorsese stakes when it comes to flamboyant editing or bravura tracking shots, but he, along with cinematographer Juan Ruiz Anchia, creates a thickly atmospheric cityscape complete with steam-hissing streets, dingy smoke-filled gambling dens and isolated pools of light around which the predators gather to stalk their prey.

The playful plot machinations and presence of a statuesque blonde with a gun make comparisons to Hitchcock inevitable and, like The Master's better films, House Of Games has a darker, more ambiguous chord resonating ominously beneath the exhilaratingly rapid pile-up of plot switcheroos. At its core, the film contains a devastating demolition of the notion of trust, with Mike revealing to Margaret that she is as corrupt and potentially criminal as he is - only he has the decency to be honest about it. The movie's terminal shot, a mysterious little final sting, tantalisingly implies that Margaret might have always been something much worse than her con-man subject ever was.