This article first featured in issue 148 of Empire magazine. Subscribe to Empire magazine today{

STRUCK BY AN URGENT CLAMOUR OF NATURE, Richard Donner claims he was on the toilet when he got the call. “Hello,” a voice at the end of the blower said. “My name is Alexander Salkind, do you know who I am?”

“No,” said Donner, director of horror smash The Omen and a man apparently Hollywood enough to have a phone in the can.

Salkind went on to reveal that he was half of the father-son production team who made The Three Musketeers and its sequel. They had the rights to Superman, but their director, Englishman Guy Hamilton (Goldfinger, Diamonds Are Forever) had been taken ill and left the project. Would Donner be interested in replacing him? After reading the screenplay Donner said he would, on the strict condition that he be allowed to bring on his own writer for a complete rewrite. The Salkinds demurred. So Donner turned them down.

“My agent kept calling me up,” he recalled later, “saying, ‘Boy, have I got a deal for you!’ I told him not to take it.”

Finally, Donner agreed to meet the Salkinds in Paris. There he was told he could bring on another writer, and Donner agreed the deal. And then they dropped the bombshell. The movie had been promised for Christmas 1978. Pinewood Studios and Marlon Brando had been booked for 12 days’ shooting, from March 1977. Not only that, but the plan was to shoot the sequel simultaneously, as they’d done on their Musketeers movies. Donner had just 11 weeks to ponder how on Earth he was going to convince the world that a man can fly.

The Salkinds had acquired the movie rights to Superman back in 1974 from DC Comics, which was in turn owned by Warner Communications. DC, fiercely protective of their most valuable character, had extensive veto rights over both the choice of screenwriter and the final screenplay, and submitted a list of appropriate names. The Salkinds first talked with William Goldman, who declined the project, before approaching Mario Puzo, who had won an Oscar for his screenplay for The Godfather. Puzo was intrigued by the epic scale of the legend and promptly turned in a gargantuan 500-page screenplay. “It was a well-written script, but it was a ridiculous script,” says Donner. “There was this guy, Pierre Spengler, who was going to supervise the making of the film for the Salkinds. I said, ‘You can’t shoot this because you’ll be shooting for five years.’ He said ‘Oh no, it’s fine.’ I said, ‘That’s totally asinine.’ One hundred and ten pages is plenty for a script, so even for two features that was way too much.”

Donner had other concerns beyond the script’s length. He felt it lacked the all-American feel that Donner thought the story needed. “It became like the Batman television series. I mean, they had things in there where Superman is looking for Lex Luthor and sees a bald head on the street, so he grabs the guy. The guy turns round and it’s Kojak saying ‘Who loves ya, baby?’ Stuff like that.”

Screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz was brought in to re-tune the screenplay(s) (but had to have a ‘Creative Consultant’ credit due to contractual wrangling), and between them they decided that the keyword for the whole production would be verisimilitude. Donner had it printed out on cards and sent to each production unit. “We treated it as truth. And the minute you are unfaithful to the truth, to the dignity of the legend, the minute you screw around with it, or make fun of it, or parody it and make it into a spoof, then you destroy its innocence and honesty,” he said. It was a commitment to realism that resulted in the famous tagline (originally the line that had been the distinctly corporate, ‘This Summer Warner Bros Brings You The Gift Of Flight…’).

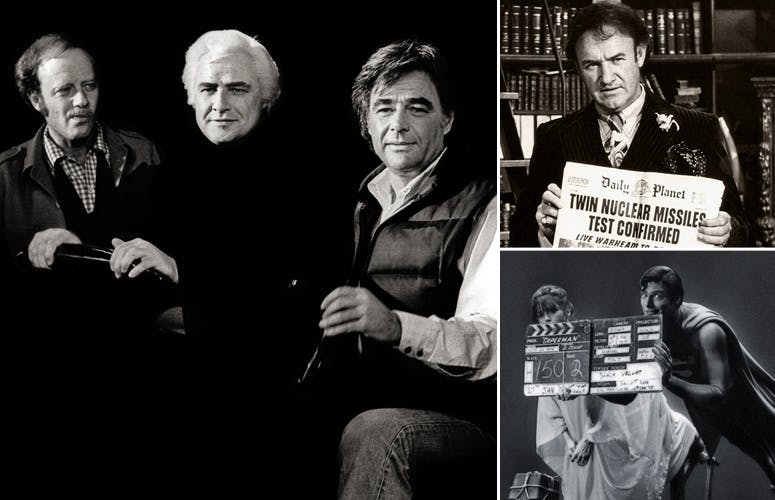

%20***Left:%20****Donner%20(right)%20on%20set%20with%20Marlon%20Brando%20(centre?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

CASTING HAD BEEN HALF COMPLETED BY THE TIME DONNER CAME ON BOARD. Gene Hackman had been paid $2 million to play Superman’s arch-nemesis, Lex Luthor, but this paled into insignificance when compared to the record-breaking $3.7 million paid to Marlon Brando for the role of Superdad Jor-El. The deal was one of the richest in movie history (in fact, richer than the quoted figure – Brando was also to snaffle 11.3 per cent of domestic and 5.65 per cent of foreign grosses, with a minimum take of $1.7 million), even though Brando would be on screen for a mere 12 minutes in the prologue sequence. Donner was unconcerned. “They didn’t buy Marlon Brando the actor, they bought Marlon Brando the name,” he commented. He had other worries, however. As yet, they didn’t have their Superman. During the previous months a range of stars had been considered for the part – reportedly Richard Gere dallied with the idea but couldn’t see himself in tights, and Robert Redford was in the frame at one point.

Anyhow, Donner wanted an unknown, reasoning that a big star would detract from the role. The Salkinds, having just written Brando’s cheque, enthusiastically agreed. Casting director Lynn Stalmaster was put on the job and rounded up dozens of potential caped crusaders. Reeve, a New York-based stage actor, was originally rejected for being too young (the screenplay had the character as 35) and too skinny for the part. After more searching Donner and Mankiewicz decided to reduce the age to thirty and go with Reeve, who immediately started bulking up, helped by David Prowse who had recently finished work on Star Wars.

SHOOTING BEGAN ON MONDAY MARCH 28 AT PINEWOOD STUDIOS, where sets for the opening Planet Krypton sequence had been built to designs by Production Designer John Barry (who had also constructed the offices at The Daily Planet at the studio, importing tons of American office paraphernalia to furnish his set – exteriors would be shot by a second unit in New York – as well as the ice palace which Superman visits to learn about his destiny). Marlon Brando had arrived a week earlier. Concerned about his star’s reputation for being difficult (“Marlon’s the kind of man that if he can collect his money and not do the deed, he’d be only too happy to do so,” Donner predicted), the director called Francis Coppola, who had worked with Brando on the infamous Apocalypse Now shoot. “Let him talk and he’ll provide his own answer,” was Coppola’s advice. This was hardly reassuring. Donner had pre-planned every second of Brando’s 12 working days. “I’d even figured out how much he cost me every time he went to the can,” he remembered. There was not going to be time for a lot of character-investigating chit chat.

%20

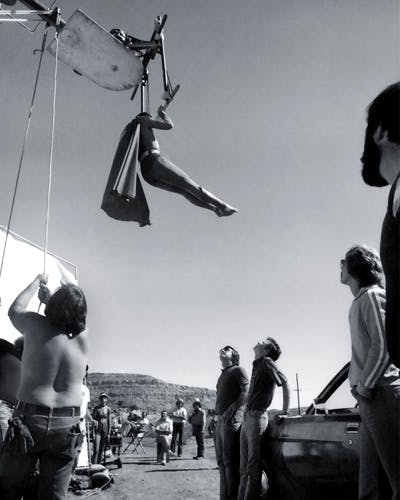

He was further alarmed when word got to him that Brando was wandering around informing people that he intended to play the part “like a big, green suitcase”. Arriving on set swathed in jumpers and scarves, and suffering from a combination of flu and jetlag, he took a look at the costumes – white jumpsuits made out of highly-reflective back projection material – and suggested, “You know, maybe I shouldn’t look like the people on Krypton, maybe I should look like a bagel.” Donner feigned calm, “but Spengler almost fainted”, he recalled. After the Krypton sequence was in the bag, the production shut down for a few weeks while Donner and his FX team continued to work on their biggest headache: how to convince an audience that Superman could fly.“I was as naïve as everyone else,” admitted Donner, shortly after the shoot. “The script would indicate that Superman flies here, he does this, he does that – without anyone ever figuring out how he was going to do it.” Since Donner was working with an actor and not miniatures, the motion control technology developed for Star Wars was virtually useless. Since Reeve would inevitably move differently in the numerous computer-controlled passes that motion control uses to build up sequences, the different elements could never match. The old system of rear projection, in which the actor was suspended in front of a screen and a pre-shot sequence projected from behind it, wouldn’t allow the graceful camera movements and interactions between Reeve and background, so was rejected.

He was further alarmed when word got to him that Brando was wandering around informing people that he intended to play the part “like a big, green suitcase”. Arriving on set swathed in jumpers and scarves, and suffering from a combination of flu and jetlag, he took a look at the costumes – white jumpsuits made out of highly-reflective back projection material – and suggested, “You know, maybe I shouldn’t look like the people on Krypton, maybe I should look like a bagel.” Donner feigned calm, “but Spengler almost fainted”, he recalled. After the Krypton sequence was in the bag, the production shut down for a few weeks while Donner and his FX team continued to work on their biggest headache: how to convince an audience that Superman could fly.“I was as naïve as everyone else,” admitted Donner, shortly after the shoot. “The script would indicate that Superman flies here, he does this, he does that – without anyone ever figuring out how he was going to do it.” Since Donner was working with an actor and not miniatures, the motion control technology developed for Star Wars was virtually useless. Since Reeve would inevitably move differently in the numerous computer-controlled passes that motion control uses to build up sequences, the different elements could never match. The old system of rear projection, in which the actor was suspended in front of a screen and a pre-shot sequence projected from behind it, wouldn’t allow the graceful camera movements and interactions between Reeve and background, so was rejected.

“We tried skydiving, but threw that out. We used some travelling mattes, which I was never happy about. We tried a flying stuntman from a 200-foot crane behind the Golden Gate Bridge in miniature – since the bridge was 60 feet long, we’d have to swing him several hundred feet behind in a long, sweeping arc. We did some night flying on cranes, which was dangerous – we shouldn’t have, but thank god we were lucky.”

In the end, a revolutionary system was developed by visual effects supremo Zoran Perisic, in which an image projected from the front of a reflective screen could be exactly synchronised with camera and character movements.

SHOOTING CONTINUNED THROUGHOUT 1977, relocating to Canada for the Smallville, Kansas sequences, and to the Rocky Mountains for the missile hijacking scene. But while the technical glitches, including massive difficulties in making Superman’s cape flutter in the wind, were slowly ironed out, Donner’s relationship with the producers, with whom he began to refer to as “the assholes”, deteriorated. Things reached crisis point when Pierre Spengler allowed miniatures supervisor Derek Meddings to leave production early.

“They tried to fire me many, many times,” Donner recalls. “But they couldn’t. Warners had director approval and there were only about four names on their list. It was me, Friedkin, Spielberg and maybe one other. But [because of Spengler’s inexperience], monies were just flushed away. I hate to see that when it should be up there on the screen.”

Relations became so strained that Richard Lester was brought in to supervise. His first decision was to abandon all work on the second movie and push on with the first. “I figured if no-one went to see the first there’d be no sequel,” Donner said. In fact, he was forced to cannibalise material shot for II to reconstruct the climax of the first movie, when a planned cliffhanger ending was abandoned.

Shooting on both films finally wrapped in August 1979 after an 18-month shoot, in which 1,250,000 feet of film had been exposed. Released on December 15, 1978 in the USA and the 23rd in the UK, Superman stayed at number one at the box office for 11 weeks, garnering a US gross of $132 million. Which must have made the call that Donner took sometime in March 1979 – whether in the lavatory or not – an irritating one. The Salkinds were firing him from the second film. The remainder of shooting on Superman II would be completed by Richard Lester. “They saw fit to replace me,” Donner sniffed, shortly after his pink slipping. “Since I completed at least 80 per cent of the film, I only hope they cannot hurt it that much."

More Superman: