As daisy age '90s hipsters De La Soul once sang 'Three is the magic number'. And to prove it some of Jaws' most telling scenes involve the dynamic of a trio. Obviously this means the holy trinity of Brody (the father), Hooper (the son) and Quint (the ghost) but it also plays out in other cast configurations. Here is a breakdown of the film's most famous three-scenes and how Spielberg uses his filmmaking nous to define and develop the relationships.

The examination of the remains of Chrissie Watkins establishes the point of Matt Hooper. Up until now he has been a smart alec frat boy in a grown-up world. Yet once the action switches to Brody and the Medical Examiner leading him into the autopsy room, the ichthyologist comes into his own.

For a start, he is dictating details into a snazzy ‘70s headset microphone that predates Madonna by some twenty years. After the medical examiner pulls back the sheet to reveal Chrissie’s remains — Dreyfuss’ little bit of hyperventilating is a thing of beauty — Hooper cleans his glasses (they are clean, we have just seen him do this in the harbour: it’s a statement of concentration) and warms to his task: he launches into a litany of medical jargon (a “mid-thorax” here, a “partially denuded bone” there), Latin fish-speak (a single sentence contains “squalus”, “unjumanus” and “Isurus Glaucous”), all the while controlling the room and growing in confidence, be it getting the medical examiner to fetch him water (Dreyfuss does a great sloosh) or keeping the air hygienic (“DO NOT SMOKE IN HERE. THANK YOU VERY MUCH.”).

To top it all, in the scene’s most famous dialogue, he displays a knowledge of London serial killers circa 1880: “Well this is not a boat accident! It wasn't any propeller! It wasn't any coral reef! And it wasn't Jack the Ripper! (here Dreyfuss splashes water on his face for added dramatic pause) It was a shark.” A frat boy has become a man.

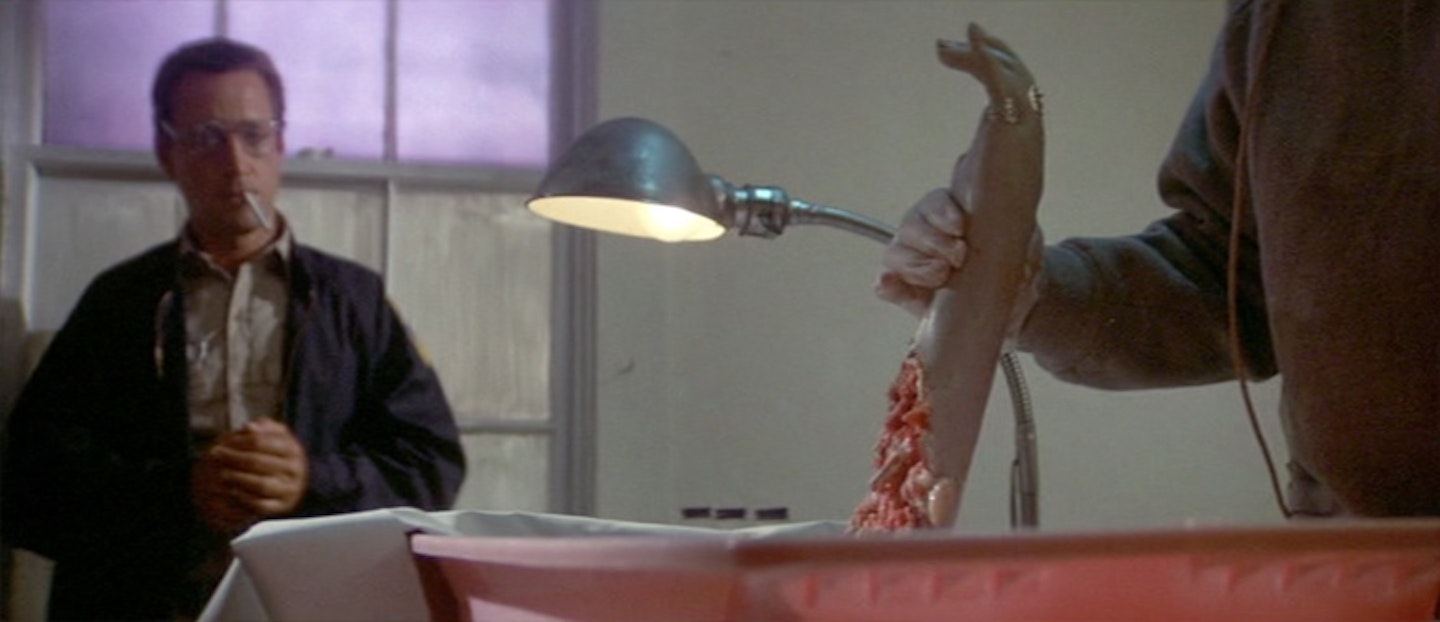

More than anything else in Jaws, the autopsy smacks of Spielberg’s TV days, covering the action in basically two set-ups and graced with perhaps the ugliest shadows in Spielberg’s career. Still the director manages to elevate the blocking from just a regular bread and butter scene. Firstly, he places Hooper centre stage but puts Brody and the Medical Examiner at either end of the room, Brody backlit against a window, the shameful M.E. (who has changed his view from a shark attack to a boating accident) almost blending into the wall, a bland man against a bland background. To give the scene added visual lift there is a lovely use of the arc of the lab lamp to almost provide a proscenium arch in the frame.

Yet the strangest moment of the scene is the close up cutaway of Chrissie’s severed arm accompanied by Hooper’s line, “So this is what happens.”

As Spielberg explained (from a question by Bryan Singer) to Empire in the 20th birthday issue, “I had cut out a line of dialogue and inside the line of dialogue I artificially manufactured a new line. Verna Fields and I pieced together ‘This is what happens’ from other things that he was saying.” Yet it doesn’t fully explain the significance of the line Spielberg manufactured or why the line was changed. Some viewers recall the line “This is what happens when a young girl goes swimming.” Jaws forum dwellers suggest it is an added-in later cutaway and then it might be the prop man holding the severed fore-arm. Either way, from The Shining to Reservoir Dogs, many of masterpieces have an in-built conundrum, a mystery that enriches the experience. This is Jaws’.

For a movie often held up as one of the greatest examples of film editing, it is perhaps surprising to discover that Jaws boasts a single shot that lasts 2 minutes and 44 seconds. We’ve just come from the most famous cut in the film — a head has popped out of Ben Gardner’s boat — and Spielberg wisely realises we need to catch our breath. So he stages the scene where Brody and Hooper double-team Mayor Vaughn, falling over each other to tell him that a Great White is on his doorstep, in one long sequence shot, the actors criss-crossing positions in the frame, moving away from the camera in impatience, returning to re-engage the argument and ending in a low angle to give the argument even more mythic dimensions.

Unlike many sequence shots of long duration and complex, borderline theatrical blocking, the style doesn’t subtract from the substance. Brody and Hooper throw history (the Jersey Beach of 1916), marine biology (sharks react to the vibrations of swimmers) and local tragedy (“It was Ben Gardner’s boat, all chewed up”) at the Mayor but Vaughn is impervious: in the dominant centre of the frame, Hamilton’s face is a model of Your Wasting Your Breath, circling back on the subject on the lost shark tooth like Paxman exposing an expenses claim.

The kicker is when the camera tracks right to reveal the AMITY ISLAND WELCOMES YOU sign now defaced with a big painted shark fin chasing a blonde cutie (based on Brian De Palma’s girlfriend of the time) on a lilo with a boat in the background. Spielberg has primed us for this moment — the sign appears early in the film as Brody drives to work — yet this time round the sign has a different, more chilling function: the blonde (Chrissie Watkins), the lilo (Alex Kintner) and the boat (Ben Gardner) are visual recaps of the plot — a kind of semiotic ‘Previously on Jaws”— and remind us of the ramifications of Vaughn’s decision to keep the beaches open. It’s sunny seaside postcard imagery as portents of dread and doom.

It is Hooper, as ever, who has the keywords. “What we are dealing with here is a perfect engine, an eating machine. It's really a miracle of evolution. All this machine does is swim and eat and make little sharks.” There is an enticing purity in that statement and, as critics are wont to point out, an inbuilt encapsulation of the film itself: what better description of Jaws is there than a “perfect engine”?

A footnote — when Hooper tells him that the graffiti of the “paint happy bastards” is proportionally the correct size, Vaughn cuts him down: “Love to prove that wouldn’t you?,” he spits. “Get your name into the National Geographic,” and exits screen left. Hooper just cackles. The National Geographic must have been big in the Spielberg household in the ‘70s. In his next flick, Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, Dreyfuss’ Roy Neary compares his UFO sighting to “those pictures in the National Geographic about the Aurora Borealis.”

The dinner scene serves a number of narrative functions. 1. It pretty much convinces Brody that Amity still has a shark problem and the Tiger shark needs to be cut open (if Hooper’s credentials needed further reinforcing, he charms Ellen with a story about how his life-long obsession with sharks began). 2. It tells us some stuff about sharks — most shark attacks happen in three feet of water, ten feet from the beach, sharks hunt in one spot till the feeding dries up — that ramps up the fear factor — that they mostly come from Brody key us into how this is turning into an obsession. 3. It reinforces Brody’s fear of the water or “drowning”. 4. And most importantly it cements the idea that Brody and Hooper are bonding. “How was your day?” deadpans Hooper, having watched him being slapped by Mrs Kintner in the previous scene. “Swell,” comes the retort. The “How was your day?” is interesting: it’s what wives in TV sit-coms of the ‘50s traditionally asked husbands in response to “Hi Honey! I’m home!” Hooper and Brody are becoming a married couple right in front of the real Mrs Brody.

Spielberg reinforces this idea visually. While the early chit-chat is played out in a wide three shot, as talk focuses on our shark, Spielberg comes in for over the shoulder shots that exclude Ellen.

It also has lovely bits of acting business too; Dreyfuss’ pause as he is about to tuck into Brody’s left over dinner; Gary’s (flirty?) embarrassment at suggesting Hooper “is in sharks”; Scheider pouring the red wine into a water glass and Hooper’s two fingered indication to Brody that he’s filled the wine glass. (There have been theses written on the depictions of class in Jaws, including whole chapters on Brody’s mishandling of wine vs. Hooper’s knowledge to let it breathe. Discuss.). Brody also breaks cinematic records for fiddling with the top of a wine bottle. But then he can do anything. He’s the chief of police.

This is the first time in the movie we see Brody, Hooper and Quint, our traveling companions for the rest of the adventure, together. The scene starts before we get there, Quint’s demands — “$10,000, $200 a day whether I catch him or not” — are laid over Brody’s exiting the hospital with Mayor Vaughn’s signed contract and we cut to him coming through the door to Quint’s abode as if in a single bound. Quint’s abode is the most interesting space in Jaws, adorned with fishing nets, ship’s wheels and skeletal shark jaws (one is in boiling on a stove getting some atmospheric texture into the scene), much to Hooper’s delight and Brody’s unease. The key set element here is the staircase. Not only does it give Spielberg something interesting to shoot through but it also literally gives Quint the higher ground when he is introduced to Hooper.

Forget man vs. shark, Quint vs. Hooper is Jaws’ epic bout. It starts as low comedy — “I’ve crewed three transpacs,” boasts Hooper. “Transplants?” misunderstands Quint on purpose — builds to a knot tying challenge — “I haven’t had to pass basic seamanship in a long time. You didn’t say how small you wanted it,” says Hooper with all the bravado of Daffy Duck upstaging Porkiy Pig — and then explodes into all out class war, Quint grabbing Hooper’s “city hands” before Hooper pulls them away, rejecting “this working class hero crap”. Brody comes between them. The tension simmers until the shark shows his face.

The moment that the Orca sets sail from Amity, Jaws becomes a different beast entirely. For an hour or so it has been part suspense picture, part conspiracy thriller, part fish-in-and-out-of-water drama. By the time it reaches the seas, it is a high adventure flick (Spielberg partly chose Martha’s Vineyard as a location because it was ideal for avoiding coast lines in the background), a men on a mission where three men have to put aside their differences and overcome their fears — Quint (class, knowledge), Hooper (machismo, experience) and Brody (water) — to save the day. In description it sounds trite, but Spielberg modulates the dynamic beautifully. The beer can-coffee cup crush is a marker of antagonism and difference without a word being spoken. The little word that Quint has with Brody after he has pulled the wrong rope to let the air canisters fall. He also doesn’t let Quint become a complete monster: after Hooper incorrectly identifies the fish Quint hooks as a “marlin or stingray”, Quint’s rebuke — “It proves one thing, Mr. Hooper. It proves that you wealthy college boys don’t have the education enough to admit when you’re wrong” is measured and reasonable. That Hooper answers by arm gestures, face pulling with added Long John Silver (“Argh Jim me lad!”) and W.C. Fields impressions (“I can’t take this abuse much longer!”) is how wealthy college boys deal with reproach.

Spielberg mostly emphasizes the differences in the group by separating the actors physically, most often in a hierarchy of shark knowledge. Hooper on top driving the boat, Quint in his chair, Brody at the stern practicing knots or setting a chum line.

It takes the shark’s arrival and a night comparing scars, both physical and emotional, to bring the group together (even during the wound comparing session, Brody is separated in his own shot until the sing-song begins). Yet at the moment where the three men seem to gelling as a group — Quint even affectionately calls Hooper “Hoop” — the salty seaman bashes the radio to bits with a baseball bat stopping Brody calling for back-up (once a cop, always a cop). Shaw’s approach with the baseball bat to camera is perhaps the most ‘70s shot in the film. Why he does this is not quite clear. You can make arguments that, Ahab-like, his obsession with the shark is so all consuming he can let nothing get in its way. Or that, as a professional fisherman, catching it “single handedly” is a point of pride. But it’s a fuzzy point in a film where the motivation is mostly crystal sharp.

Yet the shark’s reappearance brings the threesome together — it does this so often it should think about a career in marriage guidance. Watch Hooper slickly load, then hand Quint the harpoon gun to sink another barrel into Whitey. Or Hooper and Brody tie barrels to the Orca. The group of disparate men has become a slick unit and the distinct spheres of action (Hooper-bridge/Quint-chair/Brody-stern) have all broken down. The chase to sink the second (or is it third?) barrel into the shark is as exhilarating as Jaws gets — even landlubber Brody is enjoying the hunt. Perhaps he is listening to John Williams’ score.

That Brody shoots at the shark with his handgun, Quint decides to drag it towards shore and the usually verbose Hooper has nothing to offer is a sure-sign this team is running on empty. When the Orca conks out it is Quint that suggests using Hooper’s new-fangled cage thing. When the scientist descends into the deep, it is the first time the trio has been broken up for about an hour of screen time. Three have become two.