This article was first published in Empire Magazine Issue #181 (July 2004).

The movie is Heat. In a dingy office suite somewhere in Vegas, Detective Vincent Hanna makes his entrance by banging the door open with the palms of his hands. He's found his stool-pigeon, in the slick, sleazy shape of Alan Marciano, who's been dipping his wick in a suspect's wife. In ten seconds flat he's browbeaten the cocky SOB into submission, pinning him to the desk and booming his lines as if he's stashed a Marshall stack in his suit pocket. Marciano isn't just cowed, he looks on the verge of blubbing like a baby. Hanna grins, sending deranged ripples across a face so furrowed with character it seems to have experienced a period of glacial erosion: "Ferocious, aren't I?"

Oh yes, if Al Pacino is one thing – and he's so many – it is ferocious. He floods the screen with raw humanity, a tidal wave of persona pouring out of every Method-trained pore. You're not likely to miss him. He is both star and actor, in every film indelibly Al Pacino and utterly absorbed into the role. He is all the contradictions of the great screen presence: the detail is rigorous, the power overwhelming, the results often breathtaking, sometimes irritating, but always unforgettable. Where De Niro is precision, Pacino is elemental, equally obsessive but far more instinctive. Pacino dredges up his career's gallery of biting sinners and flawed strivers from the mysterious seabed of his own soul. Complicated? Of course. Passionate? To the point of madness. Ferocious? Hoo hooarrgh! "Life's on the wire," he once declared, "The rest is just waiting."

He floods the screen with raw humanity, a tidal wave of persona pouring out of every Method-trained pore.

"If the day's work demanded a lunatic," recalled Sidney Lumet, who directed him in Serpico and Dog Day Afternoon, "he was a lunatic all day long." "Darling, you have to let go sometime," warned his fabled acting coach Lee Strasberg, rather concerned his pupil was tunnelling so deep into his characters that he would never come out.

There are the tales of childhood neglect, subsequent alcoholism, romantic indifference and tribulation, a 'little-man' syndrome, all those cod-Freudian bus stops on the road to understanding the Pacino enigma, but we'll leave them for the tall tales of tacky biogs and peacock profilers. Move on if you want to plug into his raging psyche and dissect the personality so addicted to the blood-rush of evil, from The Godfather's fallen soul, Michael Corleone, to the fulminating tackiness of Scarface's Tony Montana. The point here is to lay a map across his career, to chart all those delicious, furious vicissitudes, and divine the sensuous pleasure of simply watching Al Pacino.

It's something his deaf aunts and grandmother first experienced: this tightly-wound South Bronx kid who only ventured out with his mother to the movies and would replay word-for-word the great scenes that jostled for space in his head. It started as a process of communication. Then, by his own account, he "plugged into the writers", the starting block from which the richness of character could run. "You get affected by it. When I was young I fell in love with what happened – with that kind of world. Once I fell in love with that, that was it."

For all the training at Strasberg's New York Studio, the same discipline of high-wire Methodology that layered Brando before he gobbled too much cherry pie, there is something resolutely innate about Pacino. It's why you never quite shake his presence in the role. Of course, his striking coal-black eyes and weathered cheeks make him instantly distinct, but there is always the idea that the words are welling up from within, not being read and remembered from a page. It's as if all these characters were already inside him, angles of his own personality.

Messing with the already struggling Sofia Coppola on the set of The Godfather Part III, he quipped: "When you get the urge to act, lie down and wait for it to pass." Witticism apart, that is just the point: you don't ever see Pacino act – he unleashes, Corleone, Montana, Serpico and Hanna: these characters are matched by the ceaseless surge of emotion below the surface, a coiled stillness that can well up to an almost sexual sense of release. It travels through the musicality of his voice, a vertical cadence that soars from hushed whisper to earth-shaking rant in seconds. For his bestial Cuban refugee-turned-capitalist metaphor Tony Montana, he fills his mouth with drooling sibilants and labials as if he was chewing on the very words.

Pacino doesn't simply display emotions, he charts a passage through them.

Which makes him a nerve-wracking but thrilling experience to watch, a ticking bomb waiting to go off. Not that he lacks subtlety, God forbid – he is a master of nuance and gravity. Look to the pinched spasms of indignation in The Insider's Lowell Bergman, accused of selling out his source; look to Carlito Brigante's flickering eyes in Carlito's Way, searching out betrayal in a faltering drug pick-up; and look to the creeping isolation of Michael Corleone, the all-American boy fading out of those young eyes to be replaced by a Machiavellian shadow. When Corleone finally crosses his personal Rubicon by assassinating Sollozzo and McCluskey in the restaurant, watch his face closely as the twitch of nerves becomes placated, soothed by the scent of death. Pacino doesn't simply display emotions, he charts a passage through them, more often than not toward a heart of darkness. Ironically enough, he turned down Apocalypse Now.

Such expressions of his talent are fed by seismic levels of willpower. In his younger days he was a true proponent of Method, sinking soul-deep into his roles, quite often to the point of derangement. While watching rushes of Dog Day Afternoon, playing a strung-out, bisexual bank robber with all the Herculean vim he can muster, he demanded that they ditch the day's filming and start again. He sat up all night, supping wine, awaiting some flash of Damascan light. It came: "Sonny should not have been wearing sunglasses in the bank," he explained the next day. "Ordinarily he would, but on the day of the heist he'd have forgotten them, because subconsciously he wanted to get caught." Pacino's transcendence dwells in those details. He calls it "catching the conscience".

More bizarrely, in putting together his Oscar-winning performance as a blind, embittered martinet for Scent Of A Woman, he refocused his eyes, blurring up his vision, which reportedly led to temporary blindness. When O'Donnell asked for guidance from the master, he received a terse reply: "I'm sorry, I couldn't see what you were doing."

Again in marked contrast to De Niro, forever to be the point of comparison, he can share the screen without ever giving ground. Johnny Depp (Donnie Brasco) and Russell Crowe (The Insider) feed off him to create thrilling duets, responding to the space he clears for them. Although no matter how much room he grants Chris O'Donnell, the poor fool seems totally at a loss to give Scent Of A Woman its much-needed counterpoint.

You can bisect Pacino's career into two halves, separated by a four-year hiatus from 1985-89. He had peaked so young, risen through the Godfathers and Dog Day Afternoons, to be lauded as the shining light of his generation. An edgy, forceful, extraordinary presence who then hit the wall, devastated by the critical hoots chucked at Revolution, he slunk back into the obscurity of theatre. Years passed before he took on Sea Of Love: gone were the distraught, vivid barbs of his youth that landed him five Oscar nominations, to leave a more whimsical, effortless character actor. Compare Serpico to Sea Of Love; compare Scarecrow to Two Bits; compare The Godfather Parts I and II to Part III – a transformation has occurred, a slowing in his features and an easier smile. Ostensibly, it was a good thing. He had also turned on the sex appeal, inventing a ruffled, livewire sexuality for the frothy Sea Of Love. All those jangling nerves of his younger days were still there, but resting in a contained vessel. He may just have spent those elusive four years wrestling some personal demons into submission.

In his youth Pacino would never grant an interview, and he remains reluctant, because he feels that personality creates a rift between the audience and the character. Fame is the poison of inauthenticity. "I realised that people were receptive to me," he said of his ability to charm and delight those few interviewers given an audience. "And I hadn't earned it. It felt kind of cool to sit there and not have to earn it. And think that's a trap..." What we know of Pacino has been planted by the performances, a man who'd opt for Dostoyevsky or Chekhov to write his autobiography, a man who prefers to spend his time staring curiously into the abyss.

"It is always fascinating to see how and why people go to the wrong side," claimed Pacino of his interest in dancing with the devil. "The idea of somebody who is flirting with the Big D, you know?" Despite a scattering of quasi-heroic figures such as in Sea Of Love, The Insider and the insufferably dozy Revolution, Pacino has consistently heeded the call of this "wrong side" of life. Yet to categorise this as a simple rogues' gallery of camp villainy is like deeming The Godfather just a story about crime; you can dignify Pacino with having revealed the human face of the soured American Dream more than any other actor alive. He has a personal obsession with Shakespeare's Richard III, that crookback edifice of wickedness, that has fed into all his various shades of scum and sorrow. He sealed his devotion to the character in his choppy 1996 documentary Looking For Richard, in which he interrogates New York citizen and fellow actor alike on his significance.

Indeed, he has played the hunchbacked rogue twice on stage, the second time (in 1979) to notorious career-worst notices: "Attempting Richard III has made Al Pacino the toast of Broadway," giggled People magazine. "Burnt toast, that is." Swept up in a depression, it was all the Pacino daring out of control, as he spilled about the stage spewing lines on a mortified audience. Somewhere in his head he may still be putting it right.

Yet through Michael Corleone's regal damnation, often cited as the personification of the American Dream, to Donnie Brasco's Lefty Ruggiero, a jerky, no-mark Mafia bottom-feeder, he has delivered and defined the gamut of corruption. Tony Montana is all self-denial and bloody rage, whereas Carlito Brigante is consumed by self-awareness. How apt that he got to play Satan himself in the crackpot Devil's Advocate - an actor of his skills knows full well he has been playing the devil all along. Even beyond the darkness, you can feel the threads of all his roles spin invisibly across his career, as if contained within the marrow of Pacino's bones. In Scent Of A Woman's Slade there are the coiled demons of Corleone and Brigante; in The Insider's Lowell Bergman lies Serpico's crushed idealism; and in Heat's Vincent Hanna dwell the volcanic lurches of Tony Montana.

Let's return to Heat. Pacino was heavily criticised for over-feeding the garrulous Vincent Hanna, whose heady presence swells and ebbs with such apparent one-dimensional exuberance it was declared self-parody, more "burnt toast". But this is an actor you have to study closer; there is always intricacy within the ferocity. Hanna is the yang to the yin of De Niro's control freak McCauley, a deliberately positioned opposite of swagger and frayed machismo, and how you can feel the possession of his task. This is a man consumed by what he does, almost to point of physical pain, electrically alive and intelligent – in fact it is Pacino who gives the film its momentum. Pacino might as well have been playing, well, Al Pacino.

Pacino by his peers

"He is completely incapable of doing anything fake."

~ Serpico director Sidney Lumet

"Scarface was my first demanding role and I was so terrified. The two of us in a room together was a disaster. He was much more introverted and much less accessible [then]. I tell him things he did and he can't believe it. He says, 'I did not do that.' I say, 'Yes you did. And then you said this...'"

~ Scarface co-star Michelle Pfeiffer

"Working with Al Pacino, he's one of those actors who remind you how much you like what you do, what a pleasure it is to do the job. He gave me a new respect for it."

~ Donnie Brasco co-star Johnny Depp

"There's no doubt that, by the end of Godfather II, Michael Corleone, having beaten everyone, is sitting there alone, a living corpse. There's no way that man will ever change. I admit I considered some upbeat touch at the end, but honesty – and Pacino – wouldn't let me do it."

~ The Godfather director Francis Ford Coppola

"The thing about Pacino is that he's always full of surprises and takes you to incredible places. It's hard to explain but you feel as if all you have to do is jump in his wake. It's almost like having someone do your work for you."

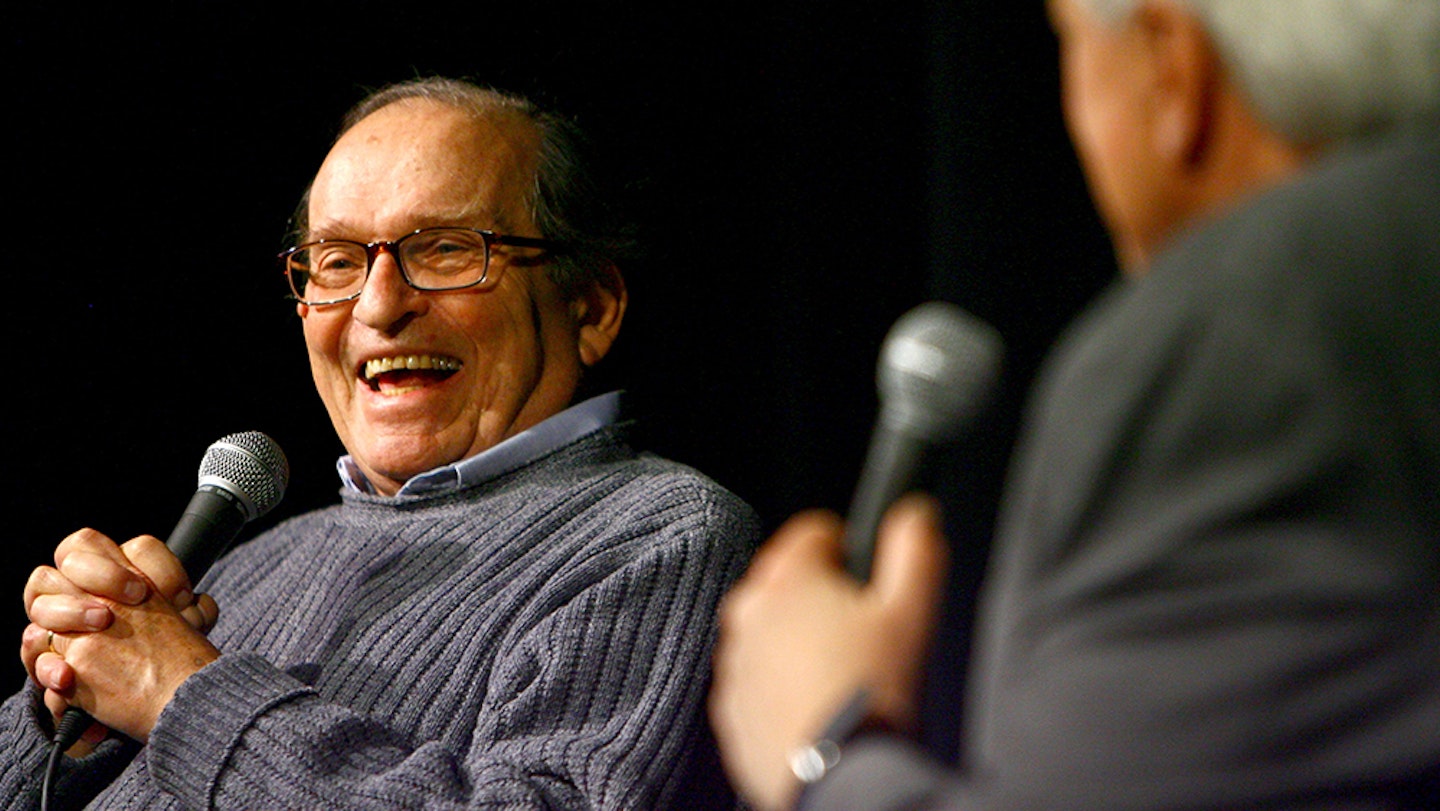

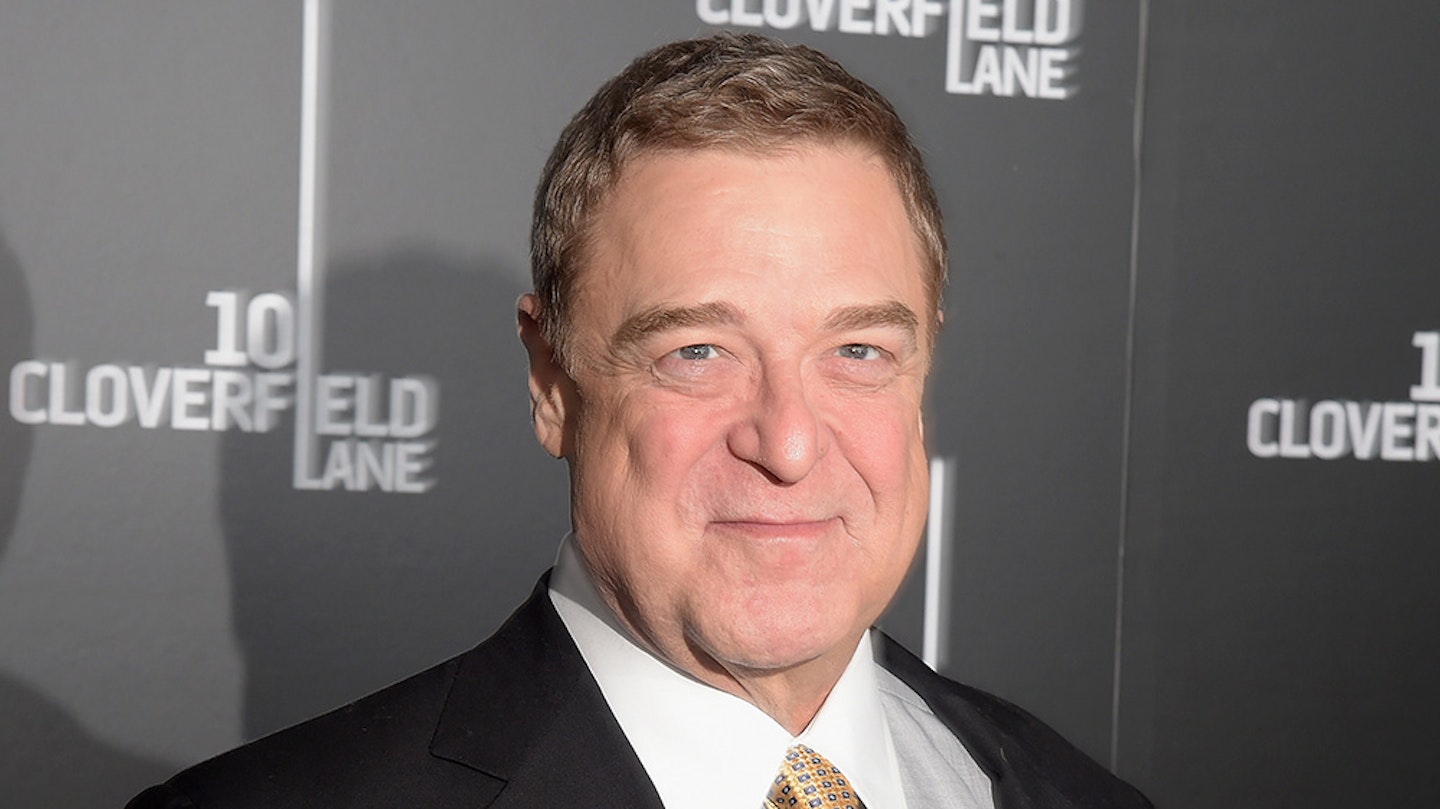

~ Sea Of Love co-star John Goodman

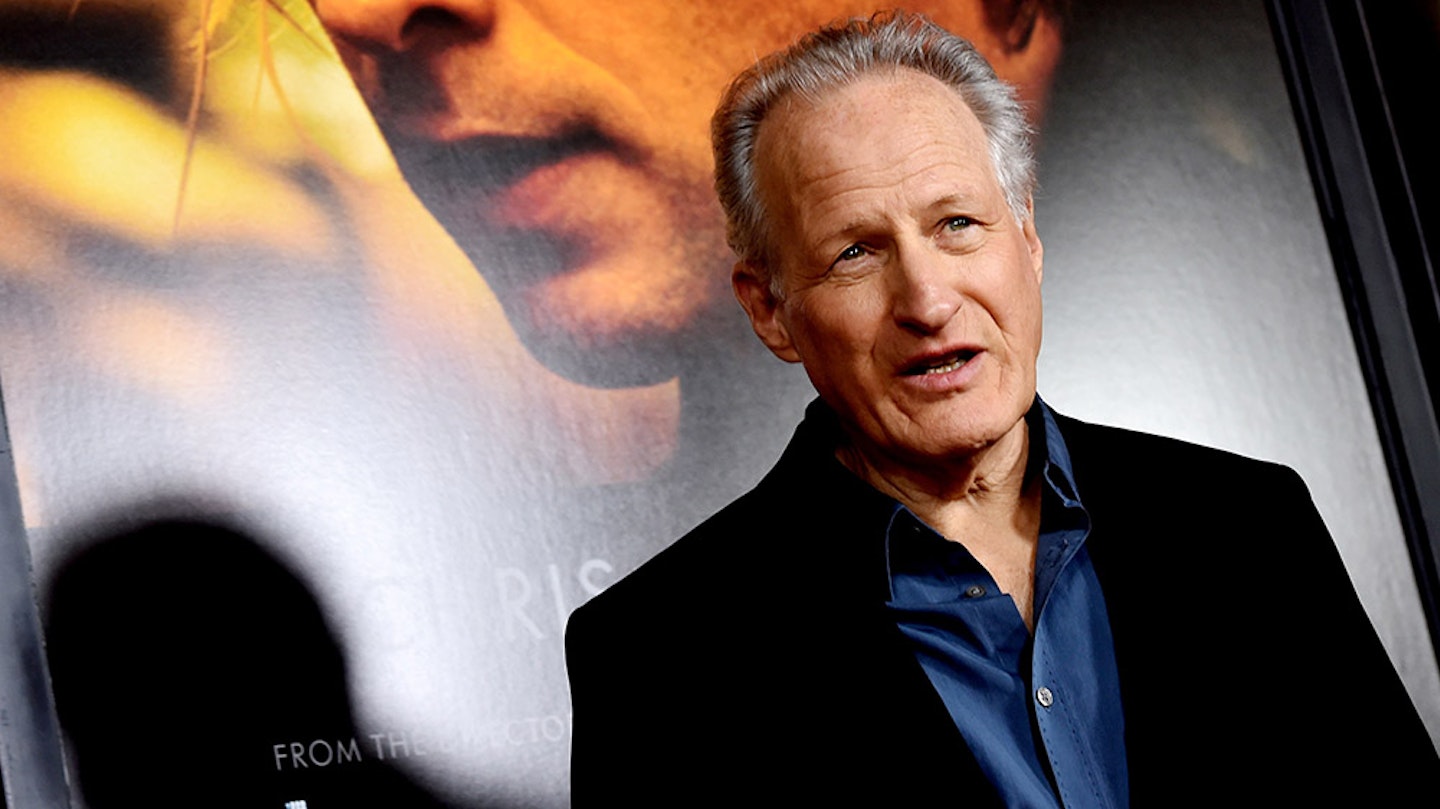

"It was take 11. There were some harmonics and nuances that were almost impossible to describe... The interplay is like two master musicians playing a duet."

~ Heat director Michael Mann

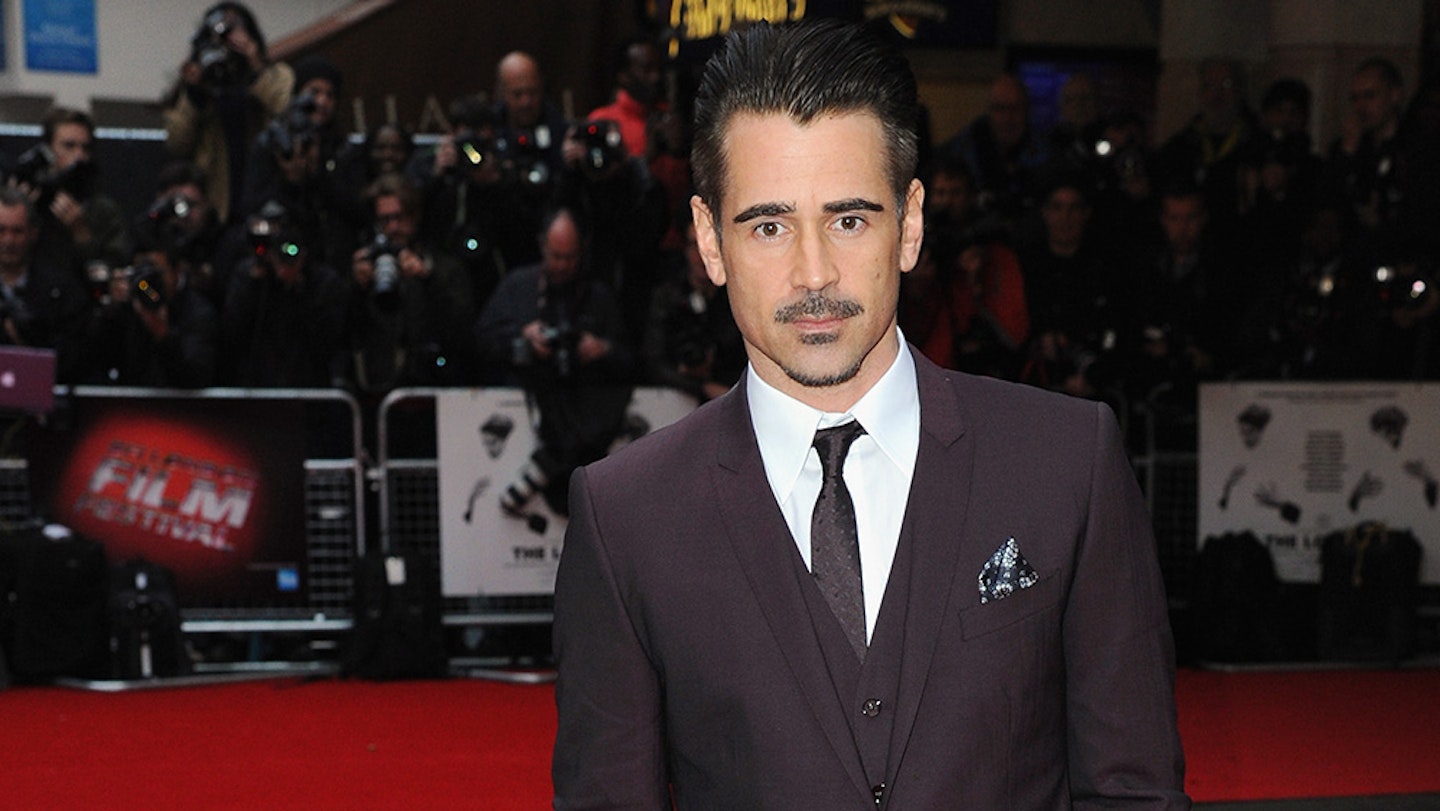

"He was serious about the work – I've never seen focus like it – but he was just a funny bastard as well! He was so smart and so intelligent, just really good company to be around, you know?"

~ The Recruit co-star Colin Farrell

"He's a very mysterious man. He's very funny, he's unique, and that gives him an interesting point of view. He's a great actor but he's very available."

~ The Devil's Advocate co-star Keanu Reeves

"There were fights with Al that were inevitably humiliating. Al said he wanted a close-up and I didn't think he needed one. He was screaming in his trailer: 'I am Al Pacino, I have never had to ask for a close-up before. You overlook my art!' I thought, 'That's awful,' and I apologised. He's Al Pacino. He's Michael Corleone, and there's all those other things he's done, and he shouldn't have to ask for a close-up. What's a close-up? Forty-five minutes. Very often Al was right."

~ Donnie Brasco director Mike Newell

"He is often indistinguishable from Dustin Hoffman."

~ Film critic Pauline Kael

"I was really surprised with Al. From a fan perspective some of the words you associate with him are ones like 'intense'. But he's pretty comfortable with himself and actually he's a pretty relaxed guy."

~ The Insider co-star Russell Crowe

"He's a little tiny man. He's just a shrimp, let's kick his ass. No, I like working with Al. Al's a good man. I love the blond hair. You like that?"

~ Insomnia co-star Robin Williams

"Women love him, men love him. He's not very competitive with other men. He has a very strong code about that. He's truly a gentleman."

~ First acting coach Charlie Laughton

"Meeting Al Pacino is terrifying. But he puts you at your ease because he knows it's terrifying – he's been dealing with that for a long time."

~ Insomnia director Christopher Nolan

Life lessons: the world according to Al

On agents... "There was a period when I didn't have an agent and I called William Morris. I said, 'I'm looking for an agent.' The receptionist said, 'What's your name?' I said, 'Al Pacino.' She said, 'Are you sure?'"

On switching off... "My problem is I identify with all characters – characters I don't play and characters in real life. I guess that's what all actors have the tendency to do."

On valuing his talent... "An actor with too much money will usually find a way to get rid of it. I poured my own money into my own film, The Local Stigmatic. Which I never released. I did some plays. All of a sudden the years passed and suddenly I owed some back taxes and the mortgage was due and I was broke. But you know what really hit me? I was walking through Central Park and this guy comes up to me – didn't know him at all – and he says, 'Hey, what happened to you? We don't see you, man.' I said, 'Well, I... uh... uh...' and he said, 'C'mon Al, I want to see you up there.' And I recognised that I was lucky to have what I've been given. You gotta use it."

On smoking... "I have these sort of health cigarettes. They're herbal and they smell a bit like grass. People think you're really cool after you have one of these but I'm really not."

On revisiting The Godfather... "I hadn't ever seen it on a big screen, because when it opened I was too nervous, and that was interesting. It was kind of like looking at an old photograph of yourself. You wonder. You wonder and say, 'I can't quite relate.'"

On research... "Some actors find research useful. Others don't. There's always something to be researched, even if you're playing a short order cook. I mean, there's always books to read, people to visit."

On being single... "Why have I never proposed in the past? I hate to say this, but marriage is a state of mind, not a contract. When I think about the law and marriage, I ask myself, 'When did the cops get involved?'"

On walking... "I used to be one of the great walkers. That's over now. I'm visible. I get spotted. I used to like getting into a kind of walking trance. All that up in front of me and around me, all the different kinds of people and characters that I could soak up... I mean, people are polite and gentle with me; it's just that you are constantly confronted and reminded of what you do."

On longevity... "One night I went to the Night Of A Hundred Stars with Lee Strasberg. There were all these people, from Orson Welles on. I remember Lee turning to me and saying, 'You know, darling, I look around and you know what I see? Survivors.'"

On theatre vs. film... "Acting's like being a tightrope walker – and there's a difference between doing it on stage and doing it in a movie. Onstage, the tightrope is way up high. You fall and you fall. In a movie, the wire is on the floor. You fall, and you get up and you do it again. Acting in a play is a different state of being. You wake up knowing you have to walk the wire at eight o'clock."

On Italian-American actors... "We seriously thought of changing our names because at that time it was unthinkable to have a vowel at the end of your name and want to be an actor."

Rage is in all of us. The actor has access to it simply because he is an emotional athlete.

On overacting... "Sometimes, I have gone over the top. It's just me, plain as passion in tatters. It's always hard to censor yourself. But as long as you take a thing and connect with the passion and that is what is communicated, I think the theatricality is valid. Anyway, as Browning said, 'A man's reach should exceed his grasp/Or what's a heaven for?'"

On why Michael kills Fredo in Godfather II... "I guess there are reasons why Michael did it. If I go back and think about it now, they have something to do with maintaining a certain sanity, because if Fredo was allowed to live, then that would have discredited everything that happened before. That's the insanity."

On rage... "Rage is in all of us. The actor has access to it simply because he is an emotional athlete. It's endemic."

On modern movies... "It's not a question of them being less good. I think it's a question of them being different. Somehow journalism, television, the media have taken up a lot of issues and expressed them, while film is becoming more esoteric and fantastical. When you think of Dog Day Afternoon, that was the first time that you were seeing the media dealing with a real-life situation, where this guy's robbing a bank and it's being televised. Now something like that is run of the mill."

On happiness... "Happiness is a word... I don't know... It's a dangerous word. Maybe it's having a sense of... bringing a life to something."

On himself... "I'm really a fun-loving depressive."

Pacino's ten greatest roles

10. Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

The best ensemble cast of the 1990s revolves around Pacino's performance as Ricky Roma, the superstar salesman that hawks worthless land to befuddled buyers. Playing the token winner among so many losers, Pacino has a chance to undermine his own actorly style by showing the gears working inside Ricky's Pacino-esque act as he delivers David Mamet speeches, basking in the admiration of his outclassed co-workers but aware that the whole enterprise is rotten to the core.

Most memorable moment: Showcasing his talents by suckering Jonathan Pryce in double-quick time.

9. Scarecrow (1973)

The ‘unknown treasure’ in Pacino's career, this is a very 1970s buddy-road movie, teaming him with an equally impressive Gene Hackman as a pair of oddball drifters who hook up for a trip to nowhere. Pacino plays Francis, a.k.a. ‘The Lion’, a sailor away from the sea who plays the clown because he believes scarecrows fend off birds by amusing rather than scaring them – he convinces his gloomy ex-con friend to lighten up, but his own optimism is worn down by experience.

Most memorable moment: Pacino's Karloff moves while fending off the rapist in prison.

8. Scarface (1983)

Like many stars, Pacino got his Oscar for a caricature of his usual traits (Scent Of A Woman), but his biggest role, in every sense, is Cuban émigré hood Tony Montana, who rises from street-thug to druglord over three hours of extreme ’80s excess. Director Brian De Palma and writer Oliver Stone give Pacino a part it would be impossible to overplay: the accent alone (‘Hsai chello to mai leetle fren’!’) is a masterpiece of broad-strokes playing, and Pacino aptly abandons his usual subtlety for one of the great bad guy roles.

Most memorable moment: A death scene Godzilla would find excessive.

7. The Insider (1999)

Russell Crowe got plaudits for his whistle-blowing Jeffrey Wigand, but Pacino has an equally difficult role as Lowell Bergman, the TV producer running with the hot potato of a tobacco industry exposé, only to realise just how powerful the cigarette companies are in corporate America. Bergman could be a middle-aged, shaved Serpico – unable to resist an impossible fight.

Most memorable moment: On his cell phone, in an empty luxury beach house, Bergman realises that the network won't back him up, and that Wigand is doomed to be out in the cold.

6. Donnie Brasco (1997)

As organised crime fetcher-and-carrier ‘Lefty’ Ruggiero, Pacino is the heart of the movie. Lefty is a time-serving criminal who knows he'll never be high in the game but tries to show his protégé the ropes, delivering a convincing demonstration that for some crime not only doesn't pay, but has an appalling personal cost. Again, Pacino plays a paranoid whose worst fears are on the money, and complicates a crime drama by making the apparent hero as much a betrayer as an avenger.

Most memorable moment: The "And it's your best friend they send to do it" speech.

5. Serpico (1973)

Frank Serpico was a hero for the 1970s – a rogue cop in the Dirty Harry mode who adopted a hippie look for his undercover work, and became famous not for busting French Connections or Mafia bosses, but by crusading against the corruption of his own department. Pacino transforms from callow youth to experienced survivor, losing all his emotional ties – and struck down with a crippling paranoia as he realises he's as likely to get a bullet in the back as the chest.

Most memorable moment: Just sitting there at the end with only his dog for company.

4. Carlito’s Way (1993)

Reteaming with Brian De Palma and adopting another Hispanic accent after Scarface, Pacino goes against expectations in the role of Carlito Brigante by underplaying a man who has been in prison so long he is wary of showing any emotion that could be construed as a weakness. As an ex-crook determined to go straight, Pacino invests the cliché with depth, showing how the toughness that made Carlito a great hood can also make him a great honest man.

Most memorable moment: Playing pool and sensing lurking assassins he then sees off.

3. The Godfather (1973)

It's a testament to Pacino's strength in the role of Michael Corleone that it's almost impossible to believe the youth in the crisp uniform at the wedding scene is the same person as the hollow-eyed monster who shuts his wife out of his counsels (and life) in the finale. Holding his own against Brando, Duvall, Keaton and Caan (no easy feat), Pacino is the spine of Coppola's epic – and he spends much of the picture talking funny after a smash in the mouth.

Most memorable moment: Coming out of the toilet with more than just his dick in his hand.

2. Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Having essayed the definitive ruthlessly efficient crook in The Godfather, Pacino played the great bungling loser heist-man, Sonny Wortzik, in this based-on-fact crime movie, a true-life comedy that inevitably turns tragic. The great twist is that Sonny may fail as a criminal, but becomes a short-lived hit as a media personality, enjoying his single afternoon of fame even as his peers realise how dangerous it is.

Most memorable moment: The phone call with the boyfriend (Chris Sarandon) whose sex-change operation Sonny is trying to finance.

1. The Godfather Part II (1974)

Why do connoisseurs rate the mature don Michael Corleone as Pacino’s best single role, and an even more impressive acting job than his outstanding work in the other parts of the series? The challenge is that Michael’s character arc concluded in part one, leaving him dead inside at the height of his power. The achievement of the sequel is that Pacino manages to find interesting things to say about a sad-eyed zombie, haunted by what he has lost as much as by the increasingly terrible things he feels he has to do.

Most memorable moment: Having Fredo killed.

Secret history

Al Pacino: amateur film director

Looking For Richard, Pacino's love letter to the depths of Shakespeare, may look like the actor's first foray behind the camera, but a little digging reveals he has directed two films previously that have never seen the light of day. Immediately following the failure of Revolution, Pacino financed a 56-minute film version of The Local Stigmatic, a play by Heathcote Williams that Pacino had headlined in 1969. Introduced to American audiences by Harold Pinter, the piece centred on Graham, a vicious greyhound-track bookie who arranges the brutal beating of an elderly actor for no other reason than the actor's notoriety. "Fame is the first disgrace," rants Graham, "because God knows who you are," a line that echoes Pacino's attitude towards his own celebrity.

Co-directed by David Wheeler, who had staged a revival of the play in the mid-'70s, The Local Stigmatic was really Pacino's baby, who spent the next few years chopping and changing the work, refining it in a process akin to theatrical rehearsal. In 1991, screenings at Harvard and The Museum Of Modern Art saw the film make its public bow, yet Pacino declared it still needed more work. It is still gathering dust in Al's attic.

"It was an experimentation," is the Pacino verdict on The Local Stigmatic, "an interesting way of learning more about making movies. You know, it surprised me that you could have been making films for 20 years and still not really understand the mechanics until you make your own."

Post-Looking For Richard, Pacino embarked on another cinematic retread of a stage play. Based on a play by Ira Lewis, Chinese Coffee sees two struggling Greenwich Village creative types (Pacino and Jerry Orbach) discuss love, life and their own friendship into the wee small hours. A kind of shouty version of My Dinner With Andre, Chinese Coffee screened at the Telluride and Toronto Film Festivals to strong notices. The film is still awaiting anything like a proper exhibition.

"I have worked with many great film directors and seen that there is a level of filmmaking that I can never get to so I don't even bother," says Pacino, justifying his hardly full-on filmmaking appetite. "I just enjoy engaging in film as an amateur. I don't have the pressure of having to deliver. I am off the hook."

Classic scene

Dog Day Afternoon: the phone call

SETTING THE SCENE

Sidney Lumet's satire on the media's hunger to participate in rather than report the news is as pertinent today as it was in 1975. Pacino is Sonny Wortzik, a bisexual fuck-up who attempts to hold up a bank to pay for his boyfriend Leon's (Chris Sarandon) sex change op. Harassed and hindered by bozo accomplice Sal (John Cazale), Sonny's botched heist degenerates into a siege-cum-media circus as cops, TV reporters and Joe Public camp outside. Anchored by Pacino's extraordinary ability to make his livewire idiot empathetic (it is also an early example of a star playing gay), the movie builds to a phone conversation between Sonny and Leon (reputedly improvised) in which Sonny tries to convince his lover to join him on the upcoming getaway.

CUT TO: INT. BANK

Sonny is on the phone to Leon (who is holed up in a barber shop), unaware that the cops are listening in on their intimate conversation. After listening to Leon’s hospital travails, Sonny begins a barrage of self-pity that is quickly dismissed by Leon. Stung by Leon’s venom, Sonny begins a stream-of-consciousness defence of his mindset and actions.

Sonny: You know what's happening with me. You know that. You know the pressures I've been having. Right? I've got all these pressures, you know about it. You're in that hospital there, with all them tubes coming out and want that fucking operation, right? You're giving me that shit. Everybody's giving me shit. Everybody needs money, you know what I mean? So you needed money, I got you money, that's it.

CUT TO: INT. BARBERSHOP

Leon: Yeah... well I didn't ask you to go and rob a bank!

CUT TO: INT. BANK

Sonny: No, I know you didn't ask me, I know you didn't ask me. I want, ya know, look, I'm not putting this on anybody, y'know? Nuthin’ on nobody. I did this on my own, you see. All on my own I did it. But I just want you to know somethin’. I want you to know that I'm gonna… I'm getting outta here. I'm getting a plane outta here.

And I just wanted you to know it, that's all. I wanted you to come down and I wanted to just say goodbye to ya or, if you wanted to, you can come with me. And then you are free to do what you want. That's just what I wanted to say to you, that's all.

CUT TO: INT. BARBERSHOP

Leon: I'm free to do what I want?

Sonny: (down phone) Right.

Leon: Well I'm trying to get away from you for six months and I'm gonna go with you on a plane trip, huh? Where... where... where are you going?

CUT TO: INT. BANK

Sonny: I don't know where yet. We said Algeria, I don't know. So I'll go to Algeria. I don't know yet.

CUT TO: INT. BARBERSHOP

Leon: Why are you going to Algeria?

CUT TO: INT. BANK

Sonny: I don't know why. They've got a Howard Johnson's there. So I'm going.

CUT TO: INT. BARBERSHOP

Leon: You're warped, you know that? You're really warped.

Sonny: (down phone) I'm warped. I know I'm warped.

Leon: God, Algeria... (hesitates) They walk around, they got masks on, they've got things on their heads, they're a bunch of crazy people there.

Sonny: (down phone) So what am I supposed to do?

Leon: I don't know. You could have picked a better place.

Sonny: (down phone) Like where? Sweden? Denmark?

Leon: (laughing) Yeah, like that.

CUT TO: INT. BANK

Sonny: You know what? Sal wanted to go to Wyoming. I had to tell him it's not a country. He don't know where Wyoming is. See I'm with a guy who don't know where Wyoming is. You think you've got problems.

CUT TO: INT. BARBERSHOP

Leon: Whew... So Sal's with ya, huh?

CUT TO: INT. BANK

Leon: (down phone) Why, you're better off giving up.

Sonny: I'm not gonna give up because of what I've done so far. I've gone so far with this. Why should I give up now? I can't give up.