If you use nucleocosmochronology or various computer models of stellar evolution, the sun is roughly 4.57 billion years old. And one day it will run out of fuel (firstly hydrogen, then helium) and move into a cataclysmic Red Giant phase - as opposed to the cataclysmic Red Dwarf phase, with its distinctive fusion of holograms, chicken vindaloo, and Craig Charles. What marks your average Giant from your Dwarf is, predictably, a matter of mass – how super-soaraway your particular sun is. As it is, our star's outer layers will eventually expand to consume the Earth, and even that white stuff Andrew Flintoff smears on his cheeks will do little to stave off instant incineration. It is also widely held that this is just what befell Krypton.

Such a state of affairs, confirms the enormously brainy Dr. Brian Cox (as in the eminent astrophysicist, not the original Hannibal Lecter), is scientific fact – although there is some debate when it comes to Krypton. "The one thing we do know is that we will not survive," says Cox, barely suppressing his delight. "I love the fact that we are doomed. There's also this thing called 'heat death' when all the stars boil away and explode and the planets have gone and there's nothing but light... When you realise how fragile and inconsequential we are, it gives you perspective. It's so liberating."

When you realise how fragile and inconsequential we are, it gives you perspective.

Cox also mentions that he took two years out from his big-brained studies to play keyboards in early-'90s dance combo D

Anyway, over the last two years, Cox has been making sure Sunshine doesn't lack in scientific credibility. Not incidentally, writer Alex Garland and director Danny Boyle's deadly serious sci-fi extravaganza comes with its own share of gloomy forecasting. Merely 50 Earth years hence, a lump of dark matter – or as Cox has it, "a cue ball" – has plunged straight into the core of the sun, radically accelerating its natural decline and leaving us pathetic Earthlings on the verge of extinction. "There's good science going on here," beams the unflappable Cox.

Thus a mission is launched to send a craft by the symbolic if pessimistic name of Icarus II (we soon learn that an Icarus I has previously failed) close enough to the extinguishing star to propel a massive bomb into its heart to kick-start its stuttering engine and save us all. It could happen. Theoretically. Apart from the bomb bit; that's just magnificent movie logic. "It would melt," chuckles Cox – there comes a point in any movie where the needs of drama far outweigh the laws of physics. Don't even mention gravity.

The presence of a leading astrophysicist on the film, sifting through its propositions, to scorn or praise and generally prod the film towards the plausible, tells you a great deal about 'Boyle's stubborn intentions. This is a film on the borders of what could happen, speculation rather than opera, an attempt to reinvigorate a genre wallowing in childlike whimsy with some beefy, grown-up apocalyptic thinking.

"Brian is great," says the Mancunian director. "He did blitz the actors but he didn't numb them. Brian was very good for us, He is also extremely good-looking, which excuses us casting Cillian Murphy as a physicist..."

It’s a typically sullen, mackerel-coloured pre-Christmas morning, the kind of weather one associates with visiting Wales. Sunshine is just a rumour being put about by travel agents. Inside a Soho screening room, the 50 year-old Boyle looks like a man who could do with a few rays. He is jittery, running on nervous energy, the batteries long since having given up their reserves. To say finishing Sunshine has been arduous is, well, the truth, The film is now complete, but a sense of delirium still hangs over the director. "Everything took so long," he implores, a man re-learning how to relax. "It happened so slowly. Like the forces of the universe, so slowly..."

Sunshine shot during the summer of 2005, and has been in post-production for the entirety of 2006, postponing an initial release date of October 2006 until April 2007. Boyle's face tells you everything. He has felt every second. "I have never felt it so strongly," he grimaces, "a whole chunk of my life has disappeared with this film. More than anything else I have done, I realise what a director is. You are quite an unpleasant force pushing through things, to make things right, to make things as they have to be. There are a lot of casualties along the way."

He doesn't elucidate further. What goes on in post-production stays in post-production, but you get the feeling right hands and left hands have not exactly been keeping in touch. Somewhere along the line people have walked or been pushed. Sunshine has not all been sunshine.

A whole chunk of my life has disappeared with this film...

But then, this is a film about pressure. The fictional crew, a diverse mix of personalities and vocations, gradually start to unravel as their ship closes in on the star. It's a study of human frailty as much as scientific hubris. "You've got the world's finest minds on this space station, which entails all sorts of egos," explains Cliff Curtis, who plays ship's psychologist Searle. "It's what happens when things go wrong. You've got to start making choices – life-and-death choices. This is such a psychological thriller."

Cillian Murphy, Rose Byrne, Chris Evans (who must be used to being cooked, having embodied the Human Torch in Fantastic Four), Michelle Yeoh, Benedict Wong, Troy Garity and The Last Samurai's splendid Hiroyuki Sanada fill out the cast. The international feel is entirely intentional - this is a global mission.

"I am really proud this is an ensemble film: eight people who discuss their fate, make a decision, and gradually die," boasts Boyle, whose circumvention of the Hollywood variety of star power (Murphy notwithstanding) was not entirely to his studio's liking. Luckily, the success of 28 Days Later allowed him some latitude. "This is a film very difficult to put in one of their boxes," he laughs.

Indeed, it has not been studio politics that have sapped the will from Britain's star-director, but creative obsession. Micromanaging the intricate CG work - the sun, the ship, the filigree detail of space' exploration produced by UK-based FX team The Moving Picture Company – Boyle has been stirred crazy alongside his crew. It has meant toughening up personally, bullying his film through to a standard only he can ultimately detect. What other way could there be? "Ang Lee says directors aren't particularly nice people. I sort of see what he means now. I am not an unpleasant person, but you have to be merciless. You have to push people very hard." Boyle's state of agitation doesn't necessarily reflect a malfunctioning movie. Rather one that has taken everything out of him and with which he is only starting to come to terms. Staring at the sun too long does things to your mind.

Not that he could escape. Science-fiction has had Boyle in its gravitational pull for years. While hot off Trainspotting, 20th Century Fox offered him Alien 4. He took a long hard look and declined, smelling studio pressure, imagining swarms of executive producers. Then, later, he completed his third of a prospective tri-part alien comedy for Miramax - the project was canned, leaving his corner of Alien Love Triangle, starring Kenneth Branagh and Courteney Cox, unseen. And 28 Days Later clearly borrows its essential nature from seminal sci-fi/horror combo I Am Legend.

"I do love it," confirms Boyle of the genre that has been dogging his steps. "I've been thinking about Alien recently. I couldn't have influenced Alien 4. When I read that script it had this amazing cloning idea. That they recreate Ripley... perfect her. I would have focused on that. With all those executive producers around you had no chance – it had to be an action movie. The only guy that could possibly have done it was Ridley Scott – he could have taken it back to the first film."

Yet, according to the director, when it came to Sunshine the genre came second to Alex Garland's brilliant conception. Garland had dragged him out to a Soho boozer for a creative conflab in that sunless void between Christmas and New Year. "He handed me this script, 'Sunshine'," he recalls wistfully. "I read it when I got home, rang him, said, 'Let's make this."

Experts like Brian Cox were called for. Realism was the key. As outlandish the premise, the sensibility would remain high-fidelity science. "I am not like Tim Burton or Luc Besson who can do rather flamboyant sci-fi. I like realism, then to disfigure it. This was science possible, not science impossible."

Beer-fuelled visions of stardust would soon enough transform into the biggest challenge of Boyle's career. At the very least, not having an Edinburgh, a Thailand, a Liverpool, or a London, where there is real life at the fringes of your fiction, would make Sunshine unlike anything he had experienced. It became a personal black hole, somewhere he would truly find out the extent of his own ability.

"There is nothing here but what you set out with," he says. "You have to live with that. You make some good decisions, some terrible decisions, you have to live with them and make the best of them. And it goes on and on... "

One full rotation of the Earth around the sun earlier, Empire finds the director much more at ease. We're a long way from the long, dark tunnel of post-production, and everything buzzes with potential and the thrilling, cogent science of moviemaking. There's a schoolboy enthusiasm around the world Boyle is creating. Inevitably, the film is shooting entirely on sound stages; location work is, for now, beyond even the reaches of NASA. Three Mill Studios at Bromley-By-Bow on the outer belt of London – somewhere between Pluto and Leytonstone – is playing house to the great starry yonder. "Alex thought this was a movie that needed to be made in a big environment," says Boyle. "I said, 'No, let's make this like we did 28 Days Later, with Andrew (Macdonald as producer) in Britain...' It's been 12 years since a sci-fi movie was shot here, and that was Lost In Space."

Akin to Ridley Scott's as-real policy on Alien, Sunshine's sets are impressively fully formed: sleeping quarters; medi-deck; mess; long, brightly lit corridors that link entire sets. On a separate stage is the ornate oxygen garden, made up of tiers of ventilated tubes of real mossy grass (tended in the movie by biologist Michelle Yeoh). The pièce de résistance is the multi-tiered bridge. Here switches turn on lights, data scrolls across computer screens and joysticks pivot satisfyingly in their cradles. Greenscreens are minimal under Boyle's dominion. It feels like you imagine a spaceship ought to. A real, working one. ''I'm not very good at imagining things that aren't there," admits the director later. "That's something else I learned about myself on this project."

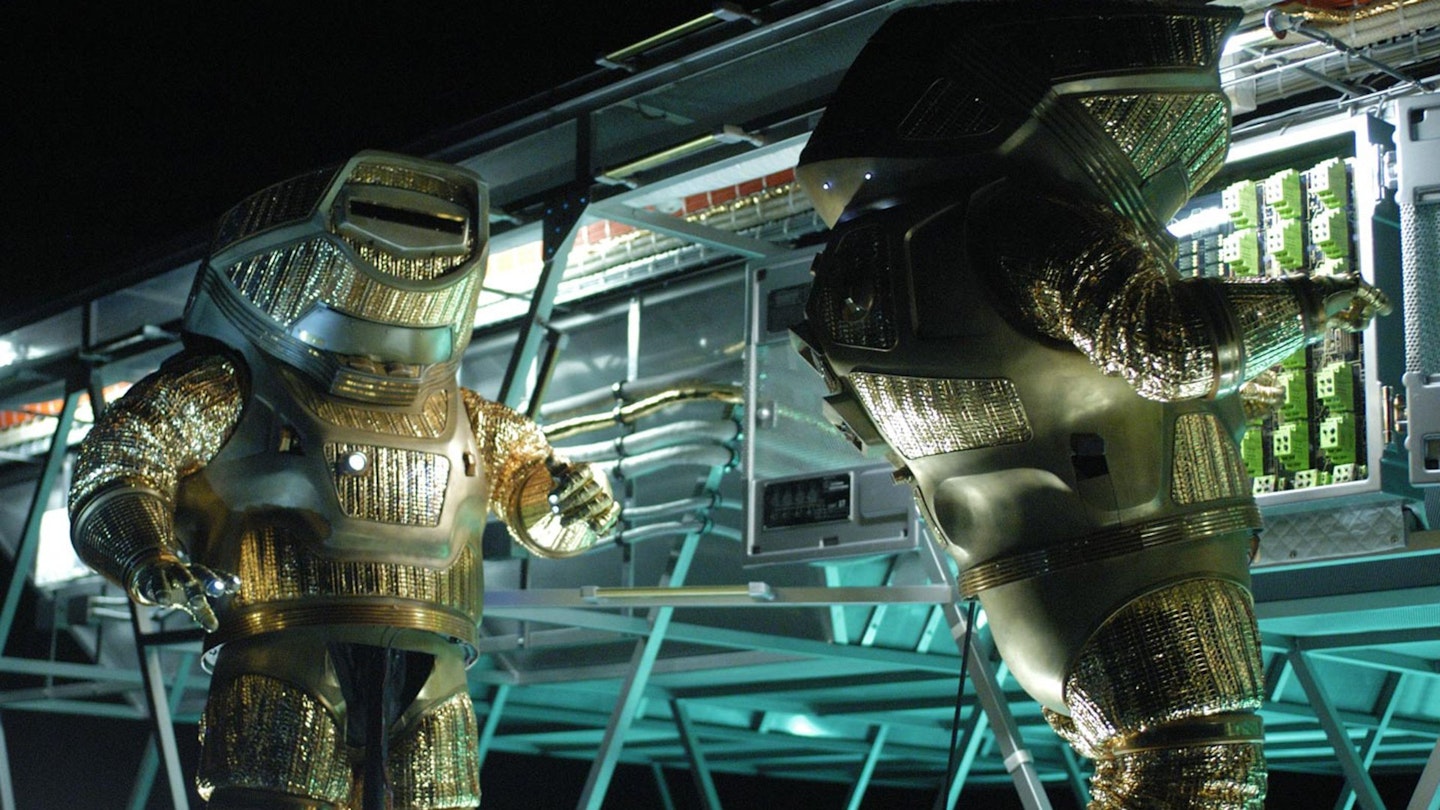

"The design is incredible, and so intricate," boasts Cillian Murphy, glancing up at an outer airlock 20 feet in the air; within, you can glimpse a rack of spacesuits coated in reflective gold. "We rehearsed in them for so long we personalised a lot of these spaces ourselves." So intent was Boyle on creating the dynamics of close-quarter spaceship living, he devised a boot camp (or is that space camp?) of full-scale immersion. The cast met astrophysicists and psychologists, NASA gurus and futurists. Murphy, as physicist Capa, got to hang out in Geneva with Brian Cox. As shooting started, Boyle noticed how he'd begun to ape the scientist's mannerisms, folding his fingers together as he pontificated. They were all installed on Heathrow flight simulators to understand the dynamics of flight ("I hate responsibility even in computer games," gripes Murphy) and took off in two-man planes that flipped and spun to make them weightless ("Scary and exhilarating," notes Murphy). And, as the coup de claustrophobia, were forced to co-habit for weeks in spartan student digs.

"It was all about tension," says Rose Byrne, who plays Icarus II's pilot, Cassie. "When you meet us we're already falling apart, just dying of boredom, dullness and depression. Danny wanted that atmosphere straight away."

It's more about experience than an idea.

Even more important were their film studies. Boyle wanted his victims to rid themselves of nonsense sci-fi – the pretty fables of Star Trek's many generations, the gleaming artifice of Star Wars – and get genre-serious: the intellectual power of 2001, the techno grimehouse of Ridley Scott's Alien (the movie's spiritual touchstone). And they weren't just moving in stellar circles: they absorbed the tension of The Wages Of Fear, the compression of Das Boot.

"In terms of science fiction, 2001, Alien and Andrei Tarkovsky's Solaris dominate the landscape," explains Boyle. "Everywhere you turn in terms of invention, they've been there. You have to doff your cap." It's been another burden – those fantastic precedents. "You have to make your own peace."

Man has never been that close to the sun, the source of all life, the power-giver worshipped as a God. The concept is mind-boggling. "We have never gone any further than the moon," explains Cliff Curtis, who has really absorbed Garland's subtextual meanderings. "We don't know. One of the most unnatural things astronauts have experienced is when they are on the dark side of the moon and can't see the Earth. Real astronauts had these experiences where they said they heard God's voice. They saw something in space... We can't possibly know the effects of travelling so close to the sun."

Sunshine aims to mix arse-clenching tension with some trippy Kubrickian side-effects. Boyle likens his journey in space to mountain movies – mountains as psychology where humans face the immensity of nature. "It's finally more about experience than an idea," he says.

After all the inter-crew crack-ups and exotic death sequences, Sunshine centres on the battle between matters of fact and matters of the spirit – science versus religion. The big question: is there something out there, a greater power than ourselves, or are we merely deluded agglomerations of Cox's cruel particles? "For all its breathtaking arrogance I believe in science," determines Boyle, noting how Garland's script forced his own belief system into focus. “I don’t believe in a God. I believe in science and advancement. There are mysteries that are impossible for us to diagnose, but science holds a chance to improve everything."

And billions of years hence save us all when the big bulb in the sky finally fails for real? "We will be able to move one day if we have to," he replies earnestly. "In fact Alex had this idea for a sequel all about that... " Boyle grins, a bit desperately. "Although I won't be doing it, I can tell you."

This article originally appeared in Empire magazine, issue 214 (April 2007). Subscribe to Empire here{