As a piece of filmmaking, Jaws is second to none. From the control of its colour palette to the clever textured use of sound design to the unerring sense of pace, Spielberg's juggling of the filmmaking elements is a tour de force of cinematic proficiency that never calls attention to itself is always in the service of story. Here we examine three key weapons — camerawork, the infamous Dolly Zoom, the editing — of Spielberg's directorial masterclass.

37 years on and Jaws remains a highpoint in film editing. Cutting the movie on location in Martha’s Vineyard, Spielberg and Verna Fields worked round changeable weather and schedules (the Kintner killing and beach reactions were shot seven months apart), a faulty mechanical shark and no coherent screenplay/blueprint to produce an object lesson in cinematic storytelling. The rhythm of individual sequences is astounding but so is the pacing of the entire movie, the ebb and flow of tension and comedy, suspense and surprise all the while giving time to allow the characters room to shine and grow. Here are five great cuts in a film that is just full of them.

- This is super simple but devastatingly effective. As Chrissie is being mauled to death, we cut to a passed out Tom on the beach. It’s a pause for breath in the tumult, both visually — the motionless body against a lovely sunrise sky is in direct contrast to all the thrashing about — and aurally — the sustained string note is the opposite of Chrissie’s screaming — that intensifies the attack when we return to it. Tom’s “I’m coming, I’m coming” also layers a sexual frisson over the yells and screams.

- It’s a key editorial choice about how you segue from one sequence to another. Time and again in the first half, Jaws uses transitions that intentionally jar as if to put the audience on edge, in the headspace of Brody. The cut from the car ferry coming into dock to the Large Lady in the green and white striped bathing suit is an ugly cut. The dominant screen direction of the ferry is opposite to the woman walking to the sea, so the eye is forced to react. It also goes from a muted light to harsh light with no establishing shot to ease us in. No good ever comes after a cut like that.

- Fields famously played a pivotal role in Jaws most famous scare. After a preview, Spielberg realized that Hooper discovering Ben Gardner’s corpse didn’t deliver the requisite jumps so he reimagined the sequence with just Gardner’s head popping out into Fields’ swimming pool, adding carnation milk for ocean clouds and silver foil for silt. Yet it is the editorial skill that garners the scare. The length the shot is held before the head jumps out. The slow build of John Williams’ music that fools us we are a long way of a jump. And the literal scream that forms part of the soundtrack. Still you can know all that, know that it is coming and it still gets you every time.

- Quint has run the slowly sinking Orca ragged. The shark has disappeared with three barrels. Exasperated, the three men sit in silence. As Hooper explains how, if using his “ant-eye shark cage”, he can pump 20ccs of strictly nitrate into the Great White Gob. Brody protests, “The shark will rip that cage to pieces.” In full close-up Hooper turns and explodes, “Have you got any better suggestions?” Cut to: Brody as the first piece of the shark cage comes into view, kicking off a niftily assembled montage of cage building (Spielberg is great at depicting processes — witness the earlier economical sequence of close-ups that tell you in deft close-ups exactly How To Go Shark Fishing when Quint first hooks the shark. If the feature film career didn’t work out, he could have made a name for himself in industrial videos). It’s a bravura knowing elision of time. Spielberg and Fields know we haven’t got time to listen to Brody’s argument so let’s just cut to the cage.

- It may only last four minutes long but aspiring filmmakers could learn more from the Kintner kid scene than three years at film school. The genius of it is Spielberg’s decision to root the whole thing from Brody’s point of view — a lesser director might have interpreted it as the kid’s story. We get a flurry of shots from the perspective of the beach — Alex on his raft, a dog with a stick, the aforementioned large lady floating, a girlfriend-boyfriend frolicking. At this point, the sound is thin, just splashes of water and the tinny sound of a transistor, perhaps indicative of how Brody has zoned them out. Brody stares intently at the sea, his vision obscured by beach dwellers walking in front of him. Yet Spielberg uses the passerby’s as natural wipes, cutting closer each time so we register Brody’s nervousness. He continues to use his colour-coded wipers to flit between the Chief’s anxious face and what he thinks is a shark fin (it turns out to be Bad Hat Harry). It may be a stylistic flourish Spielberg picked up from the French New Wave — Truffaut does similar jump-cutting patterns with a doorbell in Tirez Sur La Pianiste — but it has real meaning and impact here. Just as Brody is irritated by his field of vision being interrupted, so are we.

Irmin Roberts was a visual-effects technician who plied his trade on the likes of The War Of The Worlds, Rear Window and The Court Jester. Yet his place in cinema history is assured not by any of his effects work. Working as a (uncredited) second unit cinematographer on Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Roberts invented the 'dolly zoom' to replicate Scottie's (James Stewart) sense of losing his head for heights. Costing around $20,000 to develop, the shot has spawned perhaps more synonyms than any other technical tic in cinema; it’s known as the Vertigo shot, the Triple Reverse Zoom shot, the Trombone shot, the Stretch shot, the Contra zoom, the zido, the zolly and that doesn’t even scratch the surface of it. It is also known by debatably its most famous use: the Jaws shot.

In its simplest terms, the dolly zoom sees the camera track towards or away from the subject while the zoom lens is adjusted in the opposite direction resulting in a increased perception of depth — chiefly the background appears to change size in relation to the foreground subject matter. The effect is quick and vertiginous, the perfect way to invoke Brody’s sense of repulsion with his inability to look away. Yet perhaps the most remarkable thing is its position within the movie. Hitchcock reuses it throughout Vertigo. Spielberg almost throws it away at 24 minutes in. He knows there is better to come.

In the 35 years since Jaws, the Dolly Zoom has been a) over-used and b) transformed into a visual shorthand for almost anything; fear (Frodo cottons onto the Nazgul or enters Shelob’s cave), revelations (Michael Jackson is a zombie in Thriller), trepidation (Psycho), realisations (Simba senses a wildebeest stampede), claustrophobia (Marnie), anxiety (Quiz Show), paranoia (the diner chat in GoodFellas), coolness (La Haine), parody (OSS:117 Lost In Rio) and orgasm (Laura San Giacomo in sex, lies, and videotape).

In the 35 years since Jaws, the Dolly Zoom has been a) over-used and b) transformed into a visual shorthand for almost anything; fear (Frodo cottons onto the Nazgul or enters Shelob’s cave), revelations (Michael Jackson is a zombie in Thriller), trepidation (Psycho), realisations (Simba senses a wildebeest stampede), claustrophobia (Marnie), anxiety (Quiz Show), paranoia (the diner chat in GoodFellas), coolness (La Haine), parody (OSS:117 Lost In Rio) and orgasm (Laura San Giacomo in sex, lies, and videotape).

Spielberg had worked with cinematographer Bill Butler on his TV films Something Evil (excellent — seek it out) and Savage (okay-ish) before he piped him aboard the good ship Jaws. Unlike Vilmos Zsigmond, the cinematographer of Spielberg’s first feature The Sugarland Express, Butler was perhaps more skilled craftsman than visionary artisan but his ingenuity, knowledge and proficiency went a huge way to solving Jaws’ myriad technical problems. He created a pontoon camera raft with a waterproof housing that achieved those trademark water level shots that gave you a Shark fin POV. To stop water drops hitting the lens, Butler used the Panavision Spray Deflector that saw an optical glass spin at high speed to deflect the drops. Except for the 4th of July beach stampede where the water-lens interface adds to the panic.

Butler originally envisioned the look of Jaws to start in bright summer sunshine and then become more ominous as the shark hunt goes on but shooting at sea put pay to such a controlled palette. The first half remains a riot of vibrant primary colours. In lensing Amity, Butler was inspired by the work of painters such as Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth in their view of an America untainted by urban life.

Spielberg has described Jaws as “the most expensive handheld movie ever made” but he is mostly referring to the second half. The Amity-set scenes boast a terrific use of some more formal camerawork almost from the get-go. When drunk boy chases hot girl down to the sea, Spielberg follows the pair with an elegant track as she undresses, the sense of speed increased because they are running in front of a broken fence. Critic Nigel Andrews has identified fences as a key motif in Jaws, highlighting the fences both literal (round Brody’s house and Amity’s streets) and more metaphorical (Hooper’s cage) as embodiments of the film’s interest in man’s desire to mark out territory. It doesn’t hurt that fences also resemble shark teeth.

Spielberg has described Jaws as “the most expensive handheld movie ever made” but he is mostly referring to the second half. The Amity-set scenes boast a terrific use of some more formal camerawork almost from the get-go. When drunk boy chases hot girl down to the sea, Spielberg follows the pair with an elegant track as she undresses, the sense of speed increased because they are running in front of a broken fence. Critic Nigel Andrews has identified fences as a key motif in Jaws, highlighting the fences both literal (round Brody’s house and Amity’s streets) and more metaphorical (Hooper’s cage) as embodiments of the film’s interest in man’s desire to mark out territory. It doesn’t hurt that fences also resemble shark teeth.

Spielberg mixes it up with static shots marked by deft blocking. As Brody takes a ferry out to a group of swimmers who may be in danger, he is joined by Mayor Vaughn, Meadows and the Medical Examiner. The latter tells him that he was mistaken about Chrissie’s death — it was a boating accident apparently — and Mayor Vaughn chimes in with a cautionary tale about “panic on the 4th of July. The camera remains static, but Spielberg blocks the scene carefully, undermining Brody’s sense of authority by keeping him on the extreme left of frame. At key points, Spielberg brings the action towards the centre of frame and closer to the camera, breaking the foreground into a three-shot (Brody, Vaughn, Meadows), and then just a two shot (Brody, Vaughn) making it all feel increasingly conspiratorial. That the ferry swings through 180 degrees sees the constantly shifting background heightening Brody’s sense of disorientation that power over the situation is slipping from his hands.

Spielberg mixes it up with static shots marked by deft blocking. As Brody takes a ferry out to a group of swimmers who may be in danger, he is joined by Mayor Vaughn, Meadows and the Medical Examiner. The latter tells him that he was mistaken about Chrissie’s death — it was a boating accident apparently — and Mayor Vaughn chimes in with a cautionary tale about “panic on the 4th of July. The camera remains static, but Spielberg blocks the scene carefully, undermining Brody’s sense of authority by keeping him on the extreme left of frame. At key points, Spielberg brings the action towards the centre of frame and closer to the camera, breaking the foreground into a three-shot (Brody, Vaughn, Meadows), and then just a two shot (Brody, Vaughn) making it all feel increasingly conspiratorial. That the ferry swings through 180 degrees sees the constantly shifting background heightening Brody’s sense of disorientation that power over the situation is slipping from his hands.

The Amity scenes also contain scenes of invisible intricacy. Look at the moment where Brody and Ellen say goodbye to each other before the shark hunt begins. It starts with a left to right track following Ellen following Brody as she lists the supplies she’s packed (extra glasses, black socks, zinc oxide, Blistex), then pan rounds to set up a wide shot with Brody and Ellen in the foreground, left of frame, the Orca with Quint atop the bridge in the background. The camera moves a little closer, Brody and Ellen edge a couple of steps and we are in a close-up two shot where the couple start discussing what to tell the children about Brody’s absence (“Tell ‘em I’m going fishing”). They hug and for most directors that would be the end of the shot. But Spielberg keeps it going, Ellen watching Brody board the boat, the focus pulling to get everything into sharp focus for Quint’s Mary Lee limerick. Horrified by Quint’s coarseness, terrified for her husband, Ellen turns and runs, the camera does the opposite of the movement the shot began with as she exits the shot. It’s a shot that lasts under 2 minutes and must have required rigorous acting and technical rehearsal yet it never shows off how clever it is. That is the beauty of Jaws.

The Amity scenes also contain scenes of invisible intricacy. Look at the moment where Brody and Ellen say goodbye to each other before the shark hunt begins. It starts with a left to right track following Ellen following Brody as she lists the supplies she’s packed (extra glasses, black socks, zinc oxide, Blistex), then pan rounds to set up a wide shot with Brody and Ellen in the foreground, left of frame, the Orca with Quint atop the bridge in the background. The camera moves a little closer, Brody and Ellen edge a couple of steps and we are in a close-up two shot where the couple start discussing what to tell the children about Brody’s absence (“Tell ‘em I’m going fishing”). They hug and for most directors that would be the end of the shot. But Spielberg keeps it going, Ellen watching Brody board the boat, the focus pulling to get everything into sharp focus for Quint’s Mary Lee limerick. Horrified by Quint’s coarseness, terrified for her husband, Ellen turns and runs, the camera does the opposite of the movement the shot began with as she exits the shot. It’s a shot that lasts under 2 minutes and must have required rigorous acting and technical rehearsal yet it never shows off how clever it is. That is the beauty of Jaws.

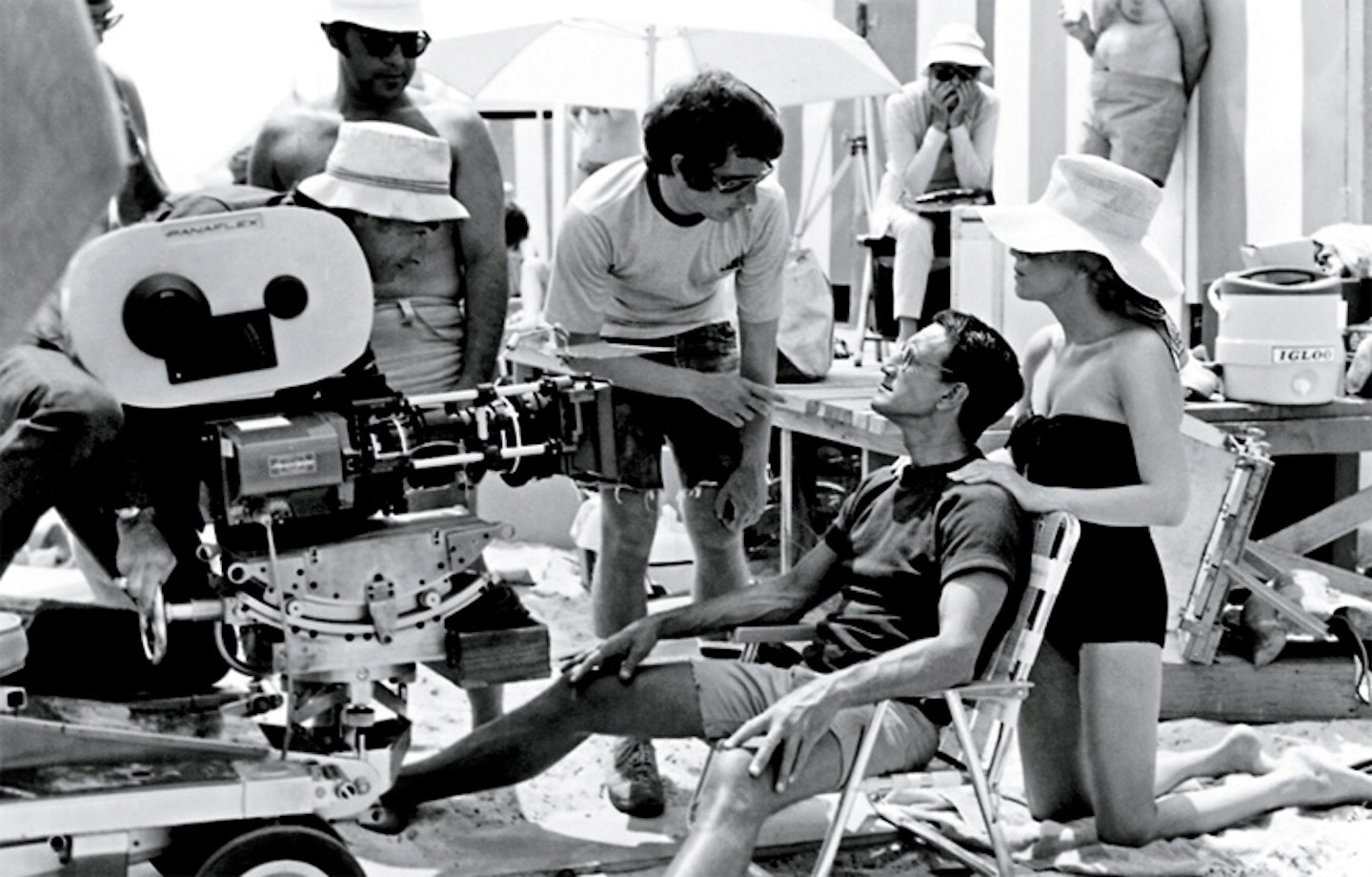

When the movie finally gets to sea, the long takes and the tripods pretty much disappear. Key here is the contribution of Michael Chapman. Best known as the DP of Scorsese’s Raging Bull, Chapman was Jaws’ camera operator and his handling of the 34lb Panaflex camera is nothing short of remarkable, whether it is simply keeping things balanced — this is some five years before Steadicam — or energising the action with little moves and adjustments to intensify the drama (ie. the tilt from Hooper’s “That’s a twenty footer” to Quint’s “twenty-five”)

When the movie finally gets to sea, the long takes and the tripods pretty much disappear. Key here is the contribution of Michael Chapman. Best known as the DP of Scorsese’s Raging Bull, Chapman was Jaws’ camera operator and his handling of the 34lb Panaflex camera is nothing short of remarkable, whether it is simply keeping things balanced — this is some five years before Steadicam — or energising the action with little moves and adjustments to intensify the drama (ie. the tilt from Hooper’s “That’s a twenty footer” to Quint’s “twenty-five”)

Yet amidst the vérité treatment, Spielberg, Butler and Chapman still craft some memorable, more structured compositions, mostly in attempts to emphasis the mythic qualities of Quint.

And by the time Quint has slugged three barrels into the beast he is sporting a bandana that resembles a hachinaki, the Japanese headband favoured by the kamikaze pilots. Just as this suggests that Quint operates under his own bushido, his slamming of his machete into the side of the boat is captured in an image of Japanese formality — in the centre of the frame is a rising sun.

And by the time Quint has slugged three barrels into the beast he is sporting a bandana that resembles a hachinaki, the Japanese headband favoured by the kamikaze pilots. Just as this suggests that Quint operates under his own bushido, his slamming of his machete into the side of the boat is captured in an image of Japanese formality — in the centre of the frame is a rising sun.