Following a well-crafted opening credit sequence in which we see the titular robot being assembled, the action kicks off in the year 2005 - throughout the film the future looks like 2000, save a few matte paintings and the obligatory flying cars - in which well-to-do Mr. Martin (Neill) surprises his wife (Wendy Crewson) and two daughters by introducing a new addition into the household: a robot (Williams), fully programmed to cook, clean, record Who Wants To Be A Millionaire, whatever. In totally predictable fashion, the automaton irks the older daughter he names “Miss” (Lindze Letherman), endears himself to the younger sprog he dubs “Little Miss” (Hallie Kate Eisenberg) - she mispronounces “android” as “Andrew”, hence giving the droid his family name - and, encouraged by Martin, begins to develop a creative, human side that takes the form of reading books, carving ickle horses and making topnotch clocks that would shame the Swiss.

The notion of robots wanting to be human is a well-worn SF conceit yet Bicentennial Man has little that is fresh to bring to the party: indeed, the design of the robot itself is formula stuff. The plot uneasily spins out over 200 years - cue dollops of ageing make-up - focusing on the relationship between Andrew and the grown up Little Miss (Davidtz), who teaches the droid the meaning of love and liberty, then sends him off into the big wide world to find his robot brethren and fall in love with Little Miss' daughter Portia (also Davidtz). Ah, bless.

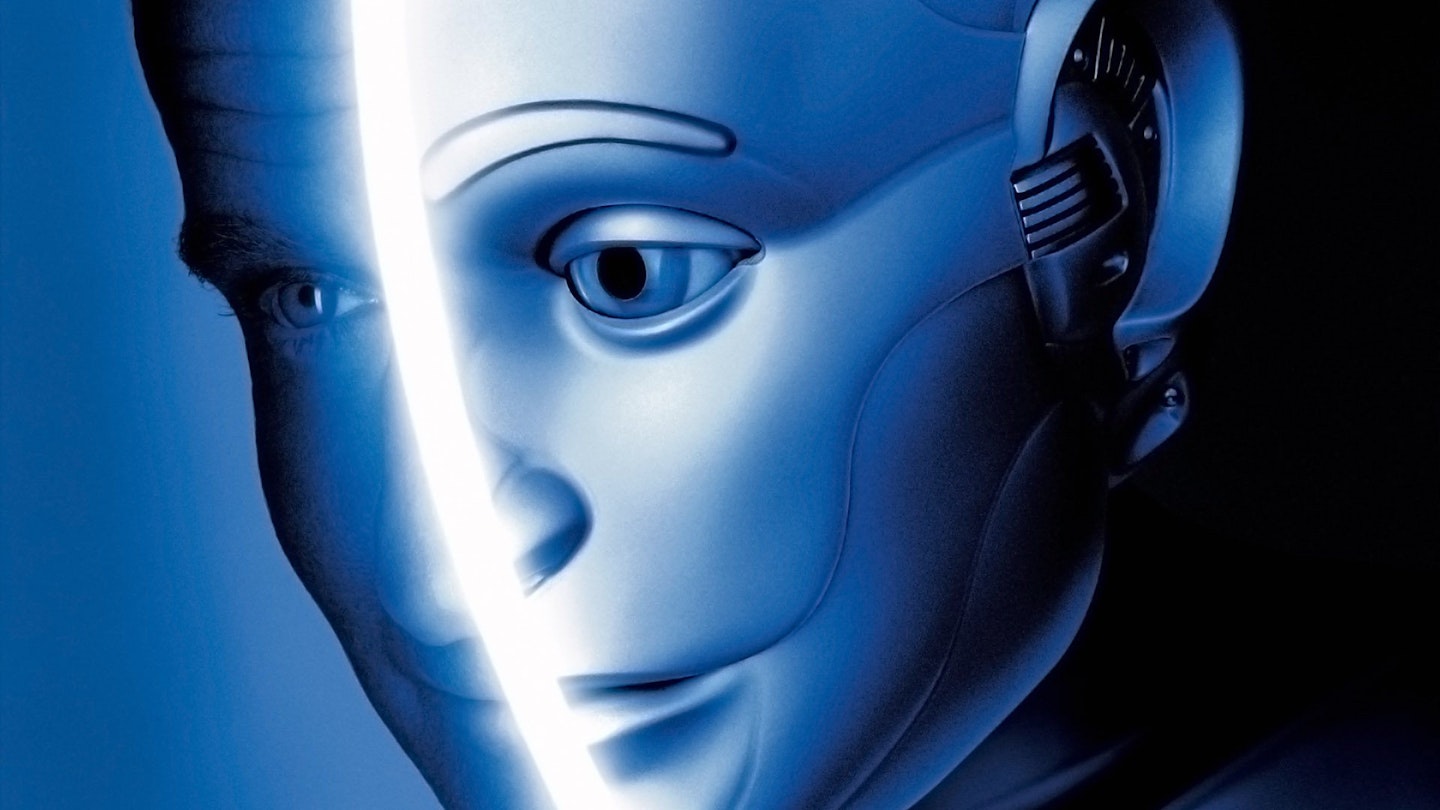

Eschewing the non-stop gag routes (if you want real comedy robots, stick with 1973's Sleeper), this trades in a schmaltzy humanism. If the studios were worried that Williams would be lost under a ton of prosthetics, they needn't have: behind the mask Williams is dignified; once he gets his own skin, however, he falls into his old mawkish ways.

Despite a strong score by James Horner and some effective moments, Columbus never creates anything other than mechanical characters and scenarios, never really delivering the emotional wallop the story dictates. Sci-fi at its sappiest.