Has any filmmaker had as much of an impact on cinema and pop culture at large as Steven Spielberg? The director of many of the greatest blockbusters, most stirring dramas, most beloved kids’ films, most exciting thrillers, and most spine-tingling sci-fi movies of all time is one-of-a-kind – rising up in the New Hollywood era of the 1970s to redefine the landscape of Hollywood in every decade since. Across 34 features, he’s run the gamut of genres, tones, and emotions, with his own signature moves and thematic occupations shining through – and now, in The Fabelmans, he’s finally telling his own story in an autobiographical drama which underpins the dramatic threads of so many of his works.

There’s the impossible question though: among his many masterful works, which one stands tallest? Team Empire gathered to vote for the best Steven Spielberg films, picking from a catalogue packed with unimpeachable masterpieces. But a consensus was eventually reached – and you can read the official ordering below. Ranked order aside, taking an overview of his astonishing career is another reminder of just how lucky we are to have him.

34) 1941 (1979)

“Steve’s direction was brilliant,” George Lucas once observed about 1941. “The idea was terrible.” Spinning off from the real-life panic that swept through Los Angeles in the aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the biggest misfire in Spielberg’s career was billed as a “Comedy Spectacular” (written by a pre-Back To The Future Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale) that for much of its running time is a laugh-free zone. Still, there are moments of jaw-dropping brilliance — a jitterbug dance sequence is as bravura as anything in West Side Story — and, in the midst of the cast shouting their heads off, has touches of sly wit (a tank becomes multi-coloured as it crashes through a paint factory, before being cleaned by careening through a turpentine warehouse). It is visually spectacular (a Ferris Wheel rolls down a pier), has a ridiculously catchy John Williams march, and is the answer to the pub question: “Which film features Toshiro Mifune, Christopher Lee and Mickey Rourke?” But it’s also monotonal, repetitive and, as critic Pauline Kael once eloquently put it, like “having your head stuck in a pinball machine for two hours.” Spielberg hasn’t made an out-and-out comedy since.

33) Hook (1991)

Spielberg himself has gone on to say that he was never particularly happy with Hook. But this late-in-life Peter Pan epic is giddily good fun, from its candy-coloured food fight to its swashbuckling showdowns. The worldbuilding is pure Spielberg magic, with Never Never Land’s bustling, fantastical vistas — especially the Lost Boys’ tree-set sanctuary — the film’s strongest hand. The filmmaker’s knack for hiring great collaborators saw Carrie Fisher board the film as script doctor, whose contributions made Julia Roberts’ Tinkerbell a funnier, fresher take on the Disney waif. As Spielberg’s first children-centric film since E.T., Hook was always a film with the odds stacked against it, and tepid reviews upon its release confirmed that it didn’t quite capture the alien caper’s enchanting spell over audiences. Yet for people who grew up with the film, there will always be that spark of delight when Peter first slices that spinning coconut in two.

32) The BFG (2016)

Let’s be clear: Spielberg’s take on the classic Roal Dahl tale is perfectly solid, with a warm performance from the legendary Mark Rylance as the BFG (that’s, Big Friendly Giant for the non-initiated), and Ruby Barnhill rising to meet him in her screen debut as 10-year-old orphan girl Sophie. But the potential here was for an all-out classic — especially when you factor in E.T. scribe Melissa Mathison on scripting duties. While there’s an over-reliance on floaty CGI giants and an oddly meandering plot, there are still moments of magic here — the Lilliputian wonder as tiny Sophie stalks through the giants’ oversized world, and the ethereal sight of the BFG capturing dreams in the nighttime London streets. Still, it’s more breezy, flawed and gentle, from a filmmaking team capable of delivering works of brilliant, fantastic genius. Snozzcumbers, anyone?

31) Indiana Jones And The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull (2008)

Talk about immense pressure: living up to the original Indy trilogy was always going to be near-impossible. And while Crystal Skull doesn’t help itself at various points (the monkey-swinging vine sequence, the CGI aliens, the goofy quicksand scene), there’s still some stellar stuff here. The opening hotrod chase, situating audiences in the 1950s, is masterful. The re-introduction of Indy himself — entering frame silhouette-first — is perfect. The shake, rattle, and rollin’ greasers-vs-jocks brawl and subsequent motorcycle chase is a blast, as is the Area 51 warehouse setpiece. Crucially, most of that comes from the film’s opening hour, which holds up far better than given credit for. But undeniably, the film begins to wobble from there, becoming tonally-muddled, with a meandering plot, off-putting turns by John Hurt and Ray Winstone, and CGI-assisted action sequences that just feel off. Shia LaBoeuf’s Mutt never connects, while the fact that Cate Blanchett’s stern Russian baddie ends up feeling bland is near-inconceivable. Still, it’s hard not to get caught up when the theme kicks in and Indy is back in action. And can we finally admit that the nuke-the-fridge sequence (inspired by an abandoned Back To The Future idea) is actually very good?

30) Always (1989)

Possibly the forgotten film of Spielberg’s career (The Sugarland Express at least gets mentioned in dispatches because it’s technically his feature debut), Always is a light-as-a-feather confection, but still much more entertaining than its detractors give it credit for. The director’s remake of 1944’s Spencer Tracy-starrer A Guy Named Joe (it appears on the TV in Poltergeist) features an impish Richard Dreyfuss as a firefighting flying ace who, killed in action, returns to haunt his ex (Holly Hunter) as she starts a new relationship with a lunkheaded pilot (Brad Johnson). As ever it is sky-high on filmmaking brio — the forest fire sequences are astonishing — but the sophistication of the artistry isn’t matched by the maturity of the relationship dynamics. It’s a minor work with major flourishes.

29) The Terminal (2004)

Spielberg’s third Tom Hanks collab is the anti-1941 — small, perfectly formed, and human. After a coup d’etat in his homeland of Krakozhia (top fictional nation name) renders him without citizenship, Hanks’ everyman Viktor Navorski is forced to stay in New York’s JFK airport until the issue is resolved. The visual comedy of Jacques Tati meets Capra-esque heartfelt cornball as Viktor plays matchmaker to airport staff (hello, Diego Luna and Zoe Saldaña) and finds romance himself with cabin crew Catherine Zeta-Jones. Spielberg constructed his own airport in a massive LA hangar and became the first movie to use a Spidercam – a camera on wires that’s now a staple in TV sports coverage – to traverse the huge space in epic shots. Still, it remains an intimate film, full of lovely grace notes (Viktor ‘tries on’ a Hugo Boss suit in a shop window reflection) and has moments of drama (Navorksi acts as an interpreter for a Russian man stopped from bringing medicines into the US) that belie its trifling reputation.

28) The Sugarland Express (1974)

With Duel being made for TV, The Sugarland Express is Spielberg’s official theatrical debut. While it may never make those dazzling debut lists occupied by Breathless, Citizen Kane, and Reservoir Dogs, it’s still an underrated treat. Inspired by a true story, it centres on spunky-but-dim Lou Jean Poplin (Goldie Hawn, terrific) who breaks her husband Clovis (a pre-Ghostbusters and -Die Hard William Atherton) out of a reform centre, takes a State Trooper (Michael Sachs) hostage, and travels cross Texas to reclaim their son Langston from foster parents. It’s a film that sees Spielberg’s already prodigious talents fully-formed, not just in the stunning choreography of the film’s car chases and crashes, but also in the sensitive work with performance and character. It has that ‘70s New Hollywood melancholy about it, but it also has a technical assurance that belongs to an earlier age — chiefly recalling the economy and simplicity of John Ford (see The Fabelmans). You feel in safe hands from the get-go.

27) Amistad (1997)

In 1993, Spielberg pulled off the double whammy of Jurassic Park and Schindler’s List in the same calendar year. Four years later, he repeated the trick to less acclaim with The Lost World: Jurassic Park and Amistad, released within seven months of each other. But the farther we get away from Spielberg’s slavery drama, the more impressive it gets. Telling the story of the legal battle over 53 African slaves who were arrested after mutiny on the Spanish ship La Amistad, it is the biggest departure from the filmmaker’s usual mode in his career, mostly told in beautiful painterly tableaux with little camera movement, while Spielberg’s cinematic intelligence courses through every frame. Occasionally it’s dramatically inert, but at its best — the middle passage, where slaves are thrown overboard tied to rocks, is as harrowing as anything in Schindler’s List — it is terrific. A fascinating companion piece/quasi prequel to Lincoln.

26) War Horse (2011)

For years after Saving Private Ryan, Spielberg steered away from war films, per se – but he squelched back onto the battlefield with an adaptation of Michael Morpurgo’s World War I story about the bonds built between men and animals amid life on the Western Front in Flanders. And it makes total sense too: part Private Ryan (mud, explosions, muddy explosions) and part E.T. (boy loves creature which is ultimately taken away), War Horse’s great strength is that it absolutely refuses to be embarrassed about leaning into the deep, sweeping sentiment at its centre, instead matching it with vast, romantic vistas. There’s a purity of heart to War Horse which it’s hard not to be swept up by – and it’s worth remembering, too, that it heralded a sea change in Hollywood. Basically nobody made World War I films in 2011. In War Horse’s wake came 1917, Benediction, and the rest.

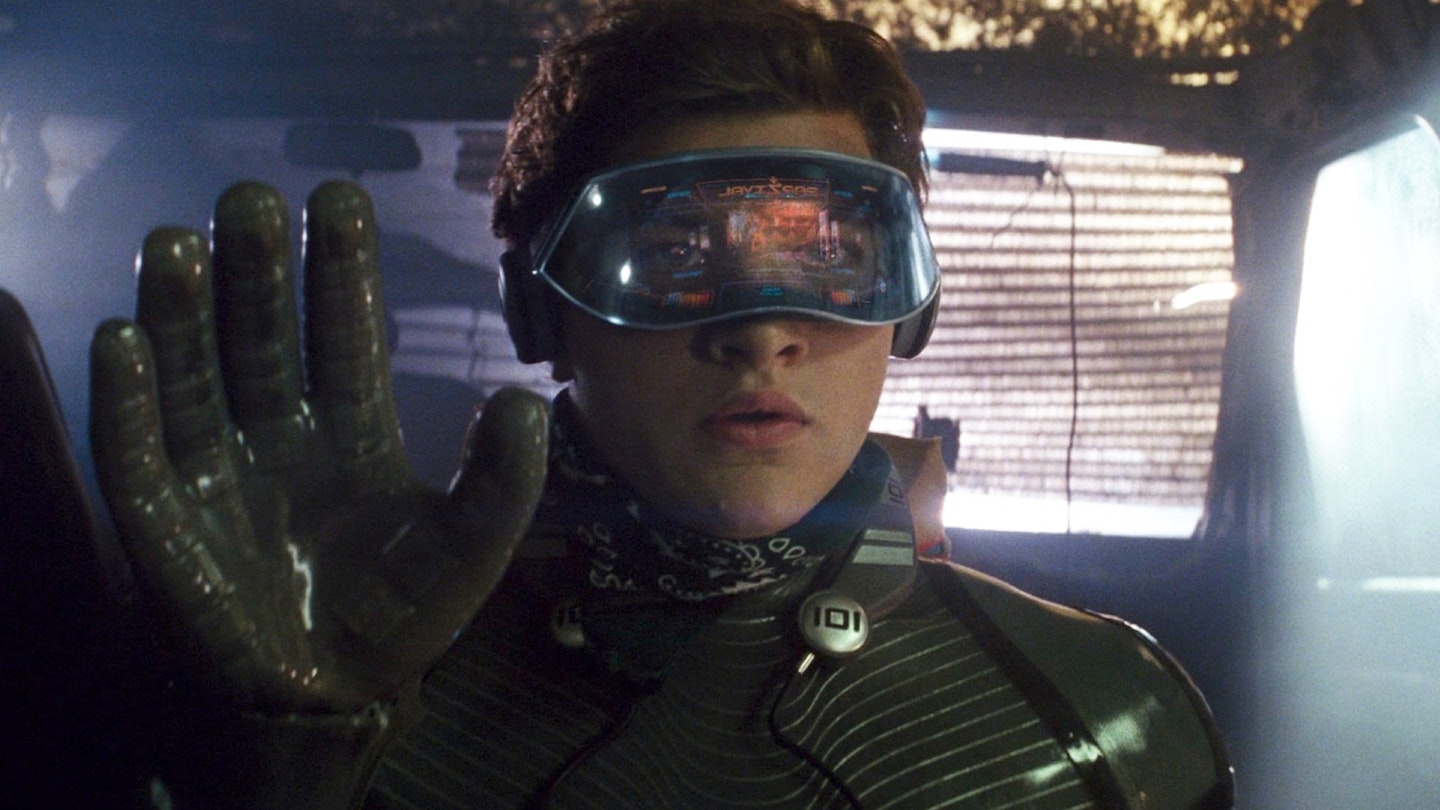

25) Ready Player One (2018)

In 2018, it had been well over a decade since Spielberg had last leant into full-blown sci-fi territory. Then along came Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One, a nerd-nirvana novel about a virtual reality dystopian future which references every pop culture touchstone worth its salt — including, not for nothing, a fair few Spielberg classics. The result is an insane candy store of nostalgia overload, a visual effects spectacle that rarely stops for breath, right up to its cameo-stacked pause-to-catch-everything finale. It’s a film with its fair share of detractors — it is, admittedly, quite silly and noisy and a little shallow. But that feels kind of the point: this is cheesy, big-screen blockbuster spectacle as only Spielberg can make it, with all the masterful craft and popcorn thrills that implies. And, in its central Shining homage sequence, it lets the director indulge his own pop cultural favourites too, gleefully running amok in the Overlook Hotel. Strap on your VR goggles and just enjoy the ride.

24) The Color Purple (1985)

This film marks the pivot between Spielberg’s years as a director who looked outside of Earth to learn more about humanity, and his later years where he was as likely to delve back into history to explore where we were going. Based on Alice Walker’s book of the same name, it follows Georgia teen Celie Harris (Whoopi Goldberg), who’s had two children by her horrifically abusive father. As she grows up, her trauma weighs on her, but she finds solace in the friendship of her husband’s son’s wife Sofia (Oprah Winfrey) and the slowly growing love of showgirl Shug (Margaret Avery). Though it’s definitely downplayed, the fact that there’s a queer love story in a massively successful film in 1985 is worth celebrating along with the vividly created turn-of-the-century Deep South. With this, Spielberg’s blockbuster era was replaced by something quieter, more thoughtful, and no less rewarding.

23) Empire Of The Sun (1987)

If much of Spielberg’s career celebrates the joy of childhood, Empire Of The Sun rings the death knell for it. Adapting J.G. Ballard’s autobiographical novel about growing up in Shanghai during the Japanese invasion in 1941, Spielberg beautifully etches the privileged life of Christian Bale’s Jamie Graham (J.G. geddit), before smashing it to smithereens as Japanese forces take control of the city in stunningly-orchestrated mayhem. Separated from his parents, Jamie lives on his wits, ending up in a prison camp as his innocence slowly ebbs away. It is, of course. the film that gifted the world Christian Bale (Spielberg bonded with the young actor by racing remote control cars with him), and much of the actor’s subsequent intensity is in evidence here, perfectly portraying an increasingly broken psyche — when he barely recognises his parents at a painful reunion, it’s the perfect riposte to those accusations of Spielbergian schmaltz.

22) The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997)

A rare Spielberg sequel, it’s easy to see why the director couldn’t resist a second round of dinosaur action. After all the breakthroughs of the original, both in its industry-evolving CGI and its outstanding use of animatronics, there’s a sense of escalation in The Lost World that could only have come in the wake of what was achieved first time around. You have Peter Stormare attacked by a mass of writhing, chittering compsognathus, two T-Rexes this time, and a slick stampede-safari sequence as InGen’s forces swoop in to round up valuable dino-assets on ‘Site B’ island, Isla Sorna. But there’s no denying that the elegance and simplicity of Jurassic Park’s plotting is absent here, replaced with a muddier narrative tangle (and a notably angrier tone) that make this return less fun, less wondrous, and less engaging. Even Jeff Goldblum’s returning Ian Malcolm is a tad dour in this one. But, when it cooks, Spielberg still delivers – the clifftop motorhome scramble is breathlessly tense, the (all-too-brief) raptors in the long grass moment remains a spectacular image, and the ultra-B-movie T-Rex in San Diego finale is as fun as it is dumb. The less said about the gymnastics-vs-raptors beat, though, the better.

21) The Post (2017)

When his proposed production of David L. Kertzer’s novel The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara collapsed, Spielberg rushed debutante screenwriter Liz Hannah’s script The Post into production. But more than just filling a hole on a dance card, the urgency (present in every frame) was driven by examining the Trump administration’s shady dealings and blatant undermining of journalism through the prism of history. Spielberg mined the story of The Washington Post’s crusade to publish The Pentagon Papers — documents that confirmed the Nixon Administration knew the Vietnam war was unwinnable — for all its 2017 resonances. The finished film never feels preachy, just punchy. It’s also a rare Spielberg story to be driven by a woman. Meryl Streep, who provided the voice for the Blue Mecha in A.I., is superb as publisher Kay Graham, beset on all sides — including by Tom Hanks’ editor Ben Bradlee — as she weighs up whether to publish, or not to publish. A nimble, entertaining workplace story, that turns a sub-editor into a hero of Indiana Jones proportions.

20) The Adventures Of Tintin (2011)

One of the great injustices of modern cinema is that we don’t appear to be getting the once-promised Peter Jackson adaptation of Tintin adventure Prisoner Of The Sun (i.e. the freaky story with the terrifying living mummy). Because Spielberg’s spin on Herge was as lively as a nest of rattlesnakes (© Captain Haddock) and as unique as a cachinnating cockatoo (also © Captain Haddock). Powered by zesty mo-cap performances by Jamie Bell, Andy Serkis, a having-the-time-of-his-life Daniel Craig, et al, it saw the director unleashed like never before, creating monster action set-pieces that thrum with wit. Just head to YouTube to remind yourself of the Bagghar chase, a high-velocity four-minute ballet of destruction involving a motorcycle, tanks, a falcon, zip-lines and a bunch of laundry, which surely counts among Spielberg’s most gleeful bit of directing ever. It’s his only time diving properly into animation as a director — and proved any doubters to be addle-pated lumps of anthracite (no need for attribution).

19) Lincoln (2012)

Adapting Doris Kearns Goodwin’s doorstop Abraham Lincoln biography Team Of Rivals remains one of Spielberg’s longest-gestating passion projects, taking thirteen years and a switcheroo of lead actors (Daniel Day-Lewis, Liam Neeson, then back to Day-Lewis) before it hit screens. The stroke of genius is how the resulting film zeroes in on just four months of Lincoln’s life, concentrating on the passing of the 13th Amendment by the House of Representatives to abolish slavery and involuntary servitude. Stylistically, it’s stately, sober Spielberg — to get into the vibe he directed the film wearing a suit — but, as Lincoln manipulates support from both sides of the House, it’s a gripping drama with more political chicanery in 150 minutes than a season of The West Wing. Day Lewis is immense as Abe, finding the man beyond the monument, backed by one of the most stacked supporting casts of the 21st Century (Sally Field! Tommy Lee Jones! David Oyelowo! Adam Driver!). Kushner’s original script ran 560 pages and, when financing was proving difficult, Spielberg considered it as an HBO miniseries. A ten-part series of this quality? Bring it on.

18) Bridge Of Spies (2015)

Bridge Of Spies is a film of two equally powerful halves. The first is a courtroom drama as insurance lawyer James Donovan (Tom Hanks) is assigned to represent Rudolph Abel (Mark Rylance), a Russian suspected of spying in the US, under increasing personal risk to Donovan’s life; the second half sees the lawyer journey to Berlin to negotiate the release of downed US airman Gary Powers (Austin Stowell) in exchange for Abel. Within the espionage genre Spielberg manages to smuggle in personal cores — his memories of watching ‘duck and cover’ public information films at school, his father’s work trip to Russia — and his directorial genius is present and correct in creative blocking that makes a men-talking-in-rooms film feel visually alive. The result is a cracking thriller featuring memorable Coen-penned dialogue, an intense plane crash, and lots of nifty spycraft. But at the heart of the film is the touching understanding between Donovan and Abel, two gentlemen in a harsh world, perfectly played by Hanks and Rylance.

17) War Of The Worlds (2005)

After years of sending benevolent E.T.s to Earth to make nice, War Of The Worlds finally saw Spielberg dispatch aliens to wreak havoc. But rather than Independence Day-style fun and games, Spielberg took H.G. Wells’ sci-fi classic and turned it into a terrifying 9/11 parable. From the Tripods zapping fleeing humans into dust, to corpses flowing down a river, to the missing persons notices tied haphazardly to fences, Spielberg tapped into the zeitgeist to create something that evoked post-Twin Towers unease and hysteria. Throw in Tom Cruise — surprisingly believable as a deadbeat dad trying and failing to connect with his kids (Dakota Fanning, Justin Chatwin) — and the result, despite all the spectacle on show, is perhaps the most harrowing summer blockbuster ever made. It’s surprising it didn’t spawn an Unhappy Meal tie-in.

16) Munich (2005)

What Schindler’s List was to Jurassic Park — a weighty historical drama released months apart from a spectacular sci-fi blockbuster — Munich is to War Of The Worlds. Spielberg’s gripping depiction of the Mossad response to the murder of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics is the director at his most engaged and thorny. It starts as a gripping procedural, as the team lead by Mossad agent Avner (Eric Bana) track down the killer responsible for the Munich massacre, shot in the propulsive, gritty style of a ‘70s thriller. But what seems like a clear-cut act of revenge becomes something much more ambiguous and interesting, with Spielberg not offering any easy answers or soothing resolutions. Moral murk is rarely this compelling.

15) A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

The mind-meld of Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick, two seemingly polar opposite sensibilities, was always going to produce something interesting — but A.I. Artificial Intelligence transcends any easy conceptualisation. Telling the story of David (an unsettling Haley Joel Osment), a robot boy who goes on an odyssey to become human (Pinocchio references abound), it’s a fascinating mix of Spielbergian emotion and Kubrickian coldness, filled with bizarre but unforgettable ingredients; a sentient teddy bear, a heart-wrenching mother-son goodbye, a carnival where robots are tortured, Jude Law as a robot gigolo, and a last act that jumps 2000 years into the future. With a screenplay by Spielberg himself, the scale is off the chain, as is the intellectual ambition. Over two decades on, it remains perhaps the weirdest, freakiest, least predictable, most challenging film on the director’s CV. And, for all those reasons, one of the most memorable.

14) Catch Me If You Can (2002)

Having saved Private Ryan, Tom Hanks and Spielberg’s second mission sent them back to France the long way round – via New York, Louisiana, and wherever else Pan Am happened to be flying – on the trail of wunderkind con artist Frank Abagnale Jr. Hanks is the dogged and slightly dorky FBI agent Carl Hanratty chasing Leo DiCaprio’s Frank, who leaves home at 16 when his parents divorce and makes ends meet with some extravagantly ballsy grifting. The smartarse kid who’s also frightened beyond his wits and the jaded company man are a great combo, and it zips along so confidently while building a version of ‘60s America that looks so gleamingly appealing that you can see why Frank wanted to grab as much of it as he possibly could. There’s a soft centre too though. Spielberg himself was a teenager when his parents split – you feel his sympathy for poor Frank, adrift in the clouds in the wake of that turmoil.

13) Duel (1971)

It’s almost inconceivable to think that Duel was originally made for TV. Spielberg’s first feature-length project — in which Dennis Weaver’s beleaguered salesman David finds himself harassed and increasingly endangered by a relentless tanker truck on a long and winding road — was originally broadcast at 74 minutes, and later expanded to a 90-minute cut. But with its expansive desert locations and near-constant suspense, it could barely feel more cinematic. Adapting Richard Matheson’s short story, scripted by Matheson himself, so many of Spielberg’s hallmarks are present: a sense of lived-in Americana in the open-road setting; an ordinary man facing down a formidable unknowable force (the truck driver himself is never revealed); a prodigious talent for knowing exactly where to place his camera for maximum impact; an instinct for combining terrifying thrills with exhilarating spills. In so many ways, it now plays as a (literal) dry-run for Jaws – lean and scary, depicting a battle not just of wills and survival, but of masculinity. For many other filmmakers, a work like Duel would be their crowning achievement. For Spielberg, it was just the beginning.

12) The Fabelmans (2023)

There have been flashes of autofiction across Spielberg’s prolific filmography, from the absent father of E.T., to the generational trauma of Schindler’s List, to the just-keep-running emotional undercurrent of Catch Me If You Can. But it took decades for the filmmaker to be ready to make The Fabelmans. It’s a film that tells the story of his own often troubled childhood, with his loving parents (played by Paul Dano and Michelle Williams) slowly drifting apart, just as the young filmmaker — here re-imagined as ‘Sammy Fabelman’, brilliantly played by newcomer Gabriel LaBelle — slowly discovers his filmmaking vocation. Equal parts tragic and funny, special shout-outs must go to Michelle Williams giving great melodrama as the Fabelman matriarch, and killer bit parts from Judd Hirsch and David Lynch. It took over 30 films to get there, but in The Fabelmans, we finally got the full Spielberg origin story; his entire career feels richer as a result.

11) West Side Story (2021)

Spielberg’s first musical is apparently also his last. “The worst day of the West Side Story shoot was the last day,” he told The Hollywood Reporter, “because I knew I wouldn't direct another musical." It’s our loss: his single entry in the genre is a spectacular redo of the iconic New York toe-tapper from Bernstein, Sondheim, and Larent, a childhood favourite of the director. Both deferentially faithful (it is closer to the original stage play than the 1961 film) and thrillingly modern, it updates the Romeo & Juliet riff with acrobatic cinematography, timely themes of immigration and gender fluidity, and star-making turns from Rachel Zegler and Ariana Debose. It all comes to a peak in the dazzling ‘America’ sequence, the frame exploding with colour and energy as the camera becomes part of the dance – you can feel how long Spielberg has been waiting to make the film as the imagery floods onto the screen. If your eyes aren’t at least misty by the end, you’re as cold as Officer Krupke.

10) Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom (1984)

Much of Indy’s second outing — with its orientalist tropes, white saviourism, and monkey-brain eating — has not exactly dated well with modern sensibilities. Spielberg himself has since distanced himself from the film, claiming in 1989 that “there’s not an ounce of my personal feeling” in it. Yet beyond the uncharacteristic darkness (both Spielberg and George Lucas were experiencing turbulence in their personal lives at the time) and not-inconsiderable political incorrectness, there’s some vintage Spielbergian filmmaking prowess on show here: from the Busby Berkeley-esque musical opener, to the ingenious and thrilling mine cart sequence, to the cinematic acting debut of future Oscar nominee Ke Huy Quan as Short Round. It may be considered the lesser entry of the original Indy trilogy, but there is still much whip-lashing adventure to be had here – and the heart-ripping torture sequences are a rare example of all-out Spielberg horror, seared into generations of kids’ heads. Hold on to your potatoes!

9) Minority Report (2002)

Hot on the heels of A.I., Spielberg continued his new-millennium turn towards a colder, more brittle style of science-fiction – with its icy hues and chilly vision of the future, Minority Report is among the director’s steeliest works. It’s a fitting tone for a film in which personal freedom comes as the cost of a world with no crime – where psychic ‘precogs’ witness murders before they happen, and ‘Precrime’ police swoop in to make arrests on not-yet-guilty parties. Tom Cruise is cop John Anderson, forced to go on the run when the precogs see violence in his future – leading to a cat-and-mouse thriller that delves into a dizzying conspiracy. Based on a Philip K Dick novel, it’s satisfyingly heady stuff – but Spielberg brings real blockbuster brio to proceedings too, from a jetpack fight sequence (complete with the jetpack-flame sizzling a burger), to a skin-crawling eye-replacement-surgery sequence, to a brawl in a futuristic car factory where a vehicle is assembled around Anderson and Colin Farrell’s Danny as they scrap. Its real legacy though? More or less inventing gesture-controls five years before the iPhone was invented.

8) Saving Private Ryan (1998)

Though Spielberg’s game-changing Second World War movie takes us deep into France — following Hanks’ Captain Miller and his ragtag bunch of leftovers and scraps who managed to survive the slaughter at Omaha beach — this is very much a post-Vietnam kind of a war movie. You wouldn’t have seen Robert Mitchum dazedly holding his own blown-off arm in The Longest Day. Brave but terrified, proud to serve but desperate to go home, Miller and co have to track down Private Ryan, the last survivor of four brothers, to get him out of harm’s way. That concussive opening sequence might be the best evocation of the pure confusion and randomness of war on film. But wipe away the guts and it’s a film about sons and fathers, and Spielberg’s father in particular – Arnold Spielberg was in the Air Corps. Spielberg Jr had been making World War II movies for 20 years before Saving Private Ryan, and it’s telling that he’s not returned to it on the big screen since. World War II? Completed it mate.

7) Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977)

A fighter squadron turns up in the middle of the desert. A warship is beached on the East Asian plains. Richard Dreyfuss fiddles with his mashed potato. As the UN investigates, Dreyfuss’ Roy Neary becomes haunted by UFOs and the image of a great mountain, while a young boy is mysteriously abducted. Given huge freedom after Jaws had devoured the box office, Spielberg went back to his earliest work, the UFO thriller Firelight — its themes of obsession and wonder (as well as several specific shots) were tractor-beamed into Close Encounters. What the 18-year-old Spielberg didn’t have to hand back then was John Williams. The musical sequence he landed on as the means by which humanity makes contact with aliens might be his most potent: there’s hope, and beauty, and wonder, and communion, all rendered in five tentative notes. While E.T. is his most thoroughly Spielbergian extra-terrestrial film, Close Encounters feels like the one that he desperately needed to make — and it’s the one that cemented him as a filmmaker of phenomenal vision who could communicate huge feelings without words. The last 10 minutes are properly transcendent.

6) Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade (1989)

When it comes to the adventures of Henry Jones Jr., Raiders tends to soak up the lion's share of applause (keep reading). But only a fool would overlook the trials of such lethal cunning that constitute Indy's third and most straight-up enjoyable adventure. Spielberg struck gold pairing Harrison Ford with both Karen Allen and Kate Capshaw, but Ford's electrifying chemistry with Sean Connery eclipses them both with ease. The pair bounce effortlessly off one another as estranged parent and child, exchanging perfectly weighted barbs ("I should have mailed it to the Marx brothers!") while painting a beautifully measured and touching father/son dynamic — despite a mere 12 year age gap between them — that ellicits as many tears as laughs ("I thought I'd lost you, boy"). This is a white-knuckle, globe-trotting hunt for the lost grail, but one that also pulls back the veil on both Indy's material past (The hat! The whip! The scar! ) and his elusive upbringing ("We called the dog Indiana!"). Throw in emotional depth, a Hitler cameo, and an immortal grail knight and you have all the ingredients for one of the greatest adventures of the modern era.

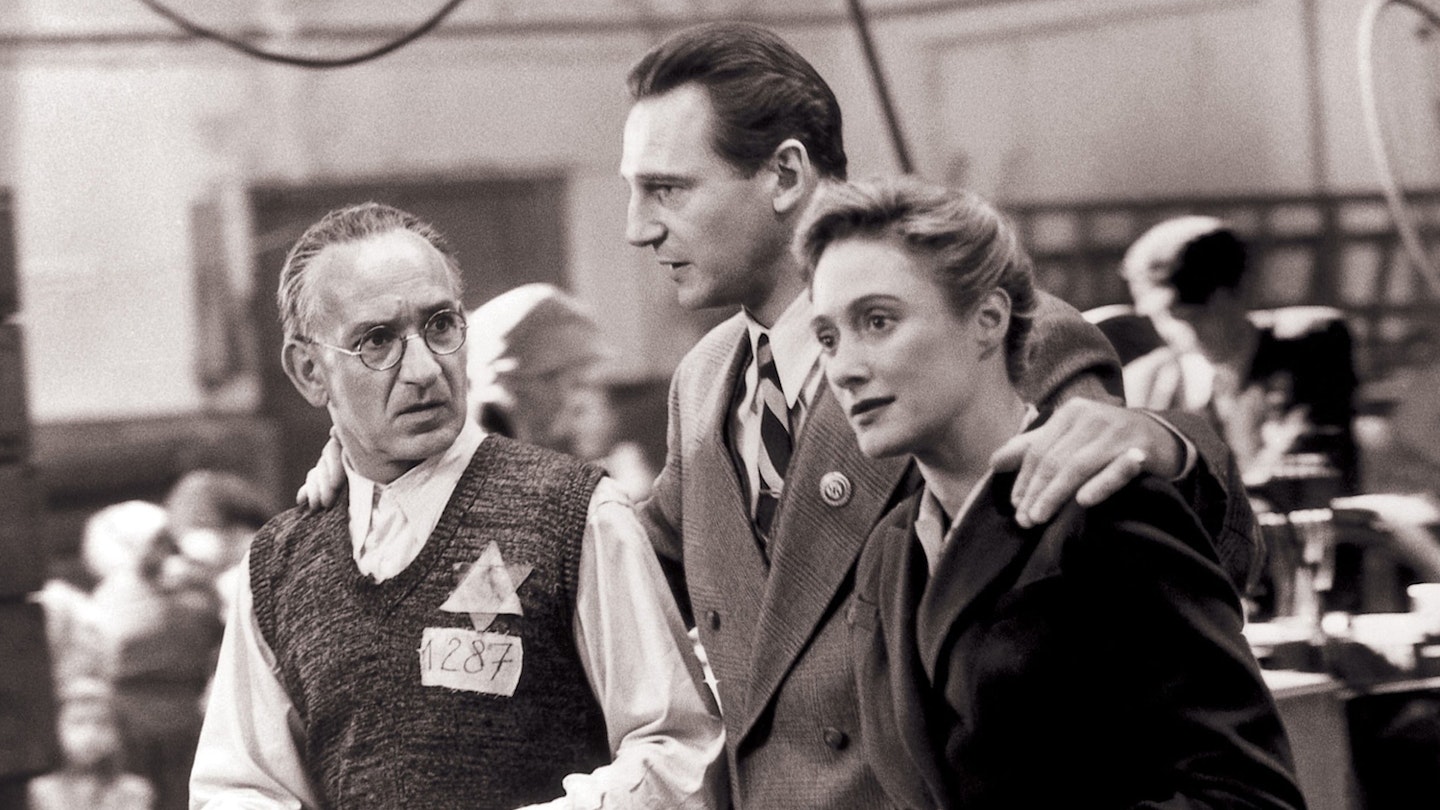

5) Schindler's List (1993)

Has any filmmaker ever had a year quite like Steven Spielberg’s 1993? In the same 12 months that saw the release of Jurassic Park — perhaps his most entertaining, popcorn-friendly crowd-pleaser — the director also released Schindler’s List, his most mature, political, emotionally-complex and deeply-felt drama. Having long wanted to pay tribute to his Jewish ancestry and the tragedy of the Holocaust in cinematic form, he suddenly felt compelled to make the film during Jurassic’s final stages (leaving his friend George Lucas to oversee the end of post-production on the dino-epic). The result is a stylistically unusual entry in the Spielberg filmography: black-and-white photography, handheld documentary-style camerawork, difficult and often harrowing subject matter. But the director’s trademark humanism and optimism still glimmers through the inhumanity of the Nazi’s genocidal evils — especially in the form of Liam Neeson’s rich, layered performance as Oskar Schindler. 30 years later, it has lost none of its devastating, soul-stirring power.

4) Jurassic Park (1993)

Artful creature-features. Boundary-pushing science-fiction stories. Rollocking adventures. Pulse-pounding survival thrillers. Spielberg had serious pedigree in all of the above before 1993 — but the way they collided in Jurassic Park resulted in one of the all-time-great blockbusters, bursting with his signature blend of wonder and terror. If the DNA goes right back to Michael Crichton’s novel – using the ‘dinosaur theme-park goes wrong’ premise as a way to tackle chaos theory and man playing god – the execution is all Spielberg: not only playing out familial themes in the journey of Sam Neill’s Alan Grant from kid-skeptic to sprog super-protector, but infusing every moment with sheer cinematic might. The spine-tingling tension of the rippling water glass. The ratcheting dread of the raptors in the kitchen. The muscular onslaught of the T-Rex rampage. The impish glee of the Dilophosaurus attack. It’s all perfectly handled, losing none of its impact 30 years on, backed by John Williams at his most soaring. With its groundbreaking early CGI effects and masterful, tangible puppeteering, Jurassic Park saw Spielberg quite literally bring dinosaurs back to life – and, once again, he changed cinema forever in the process.

3) E.T. The Extra Terrestrial (1982)

It’s hard to even think about E.T. without bawling. For whatever reason — the aching story of a child of divorce desperate for a friend, Melissa Mathison’s heart-crushing dialogue, a gobsmacking performance of absolute purity from Henry Thomas, Allen Daviau’s warm cinematography, perhaps the most beautiful score John Williams ever blessed us with, the best actual (well, kind of) flesh-and-blood alien Hollywood’s ever produced… okay, stop. For all of those reasons and so many more, every second, every frame of E.T. seizes our hearts, making us all Elliott, making us all fall in love with that exotic visitor, turning us all into kids again. It’s a testament to Spielberg that the domestic scenes – the squabbling at the dinner table (“It was nothing like that, penis breath!”), the pang of the missing father – are as entrancing as, well, the alien stuff. For all the fantasy, for all the wonder, every bit of it feels real.

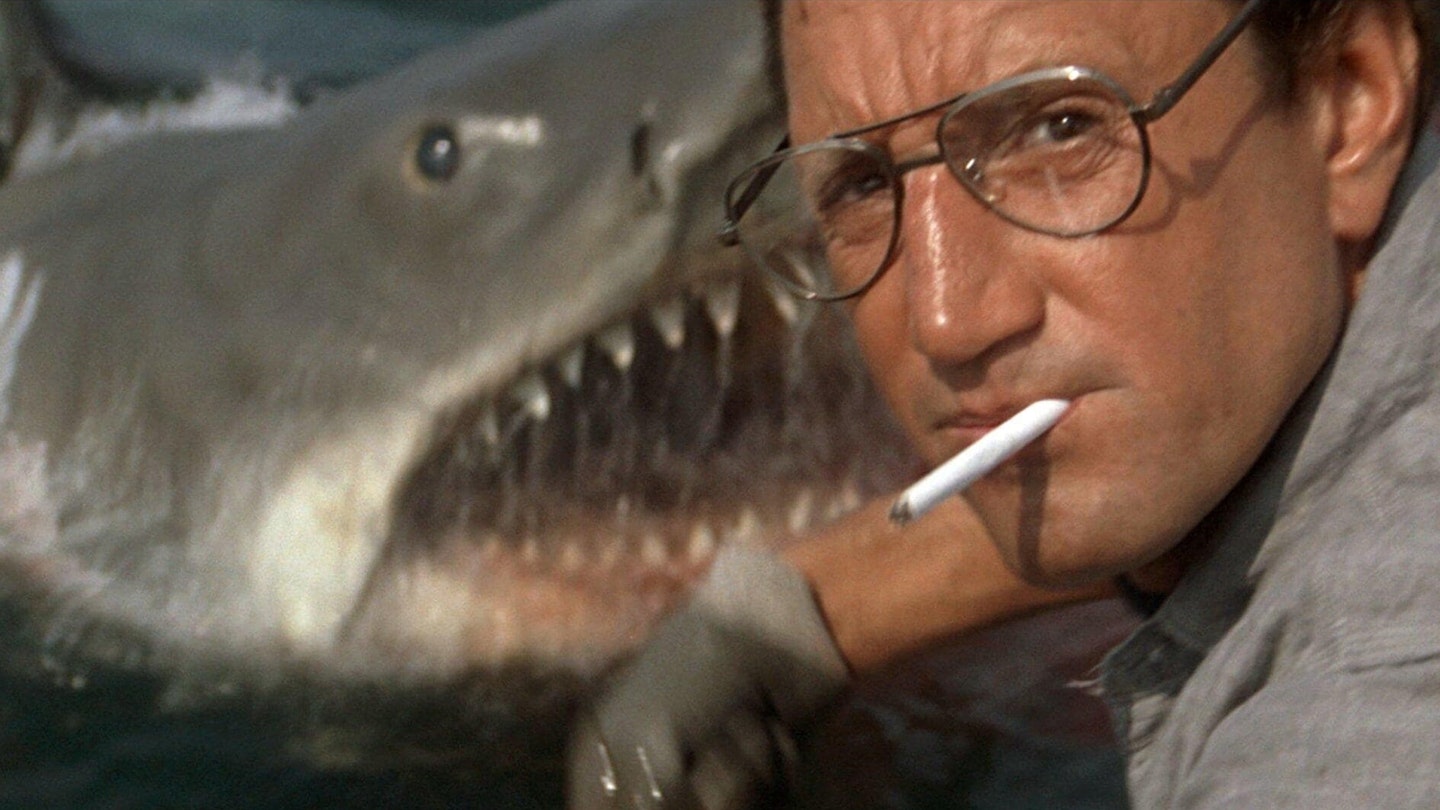

2) Jaws (1975)

The impact of Jaws simply cannot be overstated. It created the notion of the summer blockbuster. It made millions feel it wasn’t safe to go back in the water. And, for all the clear potential of his early work, it well and truly put Spielberg on the map. It was, famously, nightmarish to shoot — waterlogged, behind schedule, over budget, and with a mechanical shark that kept breaking. But for all that churn beneath the surface, what the audience sees is effortless brilliance — a tense, beautifully-shot shark-attack thriller with deeply-layered characters, outstanding dialogue, and heart-stopping moments forever burned in the cultural landscape. Roy Scheider is utterly believable as vulnerable everyman police chief Martin Brody, forced to face the reality of a murderous shark on the shores of Amity Island, teaming up with Richard Dreyfuss’ preppy marine biologist Hooper and Robert Shaw’s salty sea-dog Quint to blow it to bits. Their chemistry steers the entire ship — sure, the scary set-pieces are outstanding, but so too is Quint’s haunting USS Indianapolis monologue. But the real star here isn’t them, or even Bruce the shark — it’s Spielberg himself. The eerie shark POV shots. The mind-bending dolly zooms. The head popping out of the boat. His work here is a pure display of cinematic mastery from first minute to last — the head, the tail, the whole damn thing.

1) Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981)

If you ever want a pitch-perfect example of how to establish a brand new hero of adventure cinema and immediately propel them to icon status, look no further than Raiders Of The Lost Ark. In fact, even just the opening 10 minutes will do. In 1980, Spielberg was right in the middle of perhaps the hottest hot streak of any 20th century director, and Raiders — which saw him team up with George Lucas and Harrison Ford with the express aim to create nothing less than an action-adventure legend — reigns supreme because it brings together so many of the things that make him, him. There’s the fascination with the supernatural, of course, and the urge to mould new stories from the clay set down in his childhood. The swashbuckling ‘30s serials he and Lucas loved become a quest to stop Adolf Hitler getting his hands on the Ark of the Covenant, a relic which would make the Nazis invincible. Standing in the Third Reich’s way: curmudgeonly, adventuring archaeologist Indiana Jones. (By the way: has any man ever looked more knuckle-bitingly gorgeous than Ford in Raiders? No, he has not.) And there’s perhaps the most Spielbergian feeling of all: a giddy, breathless, Nazi-thwacking glee at the sheer fun cinema can create. It’s still as thrilling as it was more than 40 years ago. But as a certain buff archaeologist might remind us: it’s not the years, honey, it’s the mileage.