In a banner morning for the Empire Podcast, the Podbooth played host, in quick succession, to both George Miller and Guillermo Del Toro. The former has already graced this site, and with Crimson Peak out today, here's Guillermo to talk about his gothic haunted house romance and other projects past and present. The audio link is here, and what follows is a largely complete transcript of the free-wheeling conversation. Take it away, Mr Hewitt...

CH: We were talking a minute ago and you said that Crimson Peak is one of your three favourites of your own films.

GDT: Yes! Depending on the week the order of my favourites is The Devil’s Backbone, Pan’s Labyrinth and then this one. They’re kind of related to each other in very strange ways, and in equally strange ways they’re also very personal, very autobiographical.

In which ways is this one autobiographical?

Well many. Many many. Many of the things are hidden, thank God. They haven’t discovered the corpses in my basement. But there are little silly things. The opening, for example, the apparition with the girl – that happened to my mother. That’s a story she used to tell us when we were kids: that the night after the funeral of her grandmother, her grandmother came and sat on her bed. She heard the bed springs creaking and she could smell her perfume and hear the fabric of her dress, and she touched her on the shoulder. We were always very impressed by that tale! I think the movie talks a lot about love, which is a very imperfect proposition – and it should be! It’s what makes us human.

I love the portrait of the mother on the wall. It makes me crack up. It’s actually very similar to my grandmother, with whom I grew up.

And the little cameo that Lucille wears is the real cameo from my grandmother. It was also worn by Marisa Paredes in The Devil’s Backbone, and it was worn by my mother in a super-8 short I did, and it was worn by an actress in a 16mm movie I did.

So that and many other things… Edith shares my birthday, and more than anything I identify with her craft as a writer a lot: the fact that she tries to do something with stories. Her line is,”It’s not a ghost story, it’s a story with a ghost in it.” That’s a line I used many times to describe The Devil’s Backbone. And et cetera, et cetera. There are a lot of things that are deeply personal for me.

The portrait was done by David Cronenberg’s daughter – is that right?

The [source] photograph for the painting was done by David’s daughter, and then the painting was commissioned and took about six months to be done properly. What happens in movies for me is that many times, even in good movies, you’re watching a Victorian movie and then a painting, or a pamphlet or a piece of paper comes up and it has nothing to do with the style. I’m very punctilious about these things. We wanted the design of the newspaper to be of the time; we wanted the painting to feel like it took time. So it took about six months. We had to choose somebody that looked like my grandmother a little: someone who looked severe enough to make the point. Because at the end of the day, for me, in Crimson Peak, the real villains and the real origins of the horror are human. The monsters are the mother and the father that are not there.

It’s interesting that you don’t show the mother and the father; there are ghosts in the film, but not them.

Yes. Well the father is the biggest ghost: he’s completely absent. The father for me is in the house. We did the archways in the shape of a human body, and I did some silhouettes in the same shape in the patina of the walls. I made many of the windows in the house round, like eyes, so that you feel that they’re watching. The house is the family, and I think the real horror in the movie is family! [Laughs] In my adult life I started to know real horror when I started worrying about the fate of my kids. When you’re a single unit or a couple it’s much easier. When I saw The Exorcist as a kid, it didn’t scare me. I was into monster movies. It wasn’t that scary. Then I saw it as a father and it scared the bejeezus out of me!

A lot of people – parents - feel that the scariest scene in The Exorcist isn’t to do with the supernatural, it’s…

The hospital, absolutely! The two things I feel that connect brutally in The Exorcist are the hospital and the fact that if you have experienced the teenage years with any kid, there’s one day when your blessed, blissful child… you enter the room or they come downstairs and their head is twisting 160 and they’re speaking in tongues, you know? Horror always functions with commonalities: when you can identify with something that is not supernatural. The Omen always works on the fear of the otherness of the kid. When you’re a father, there’s a moment when your power only reaches so far, because your kid has his own identity.

Richard Donner actually doesn’t believe that The Omen is supernatural. He sees it as just a series of unfortunate coincidences.

And a very big black dog. And they hired the wrong nanny!

But director’s intent is always interesting. I was just talking to George Miller about some of the fan theories around Mad Max: Fury Road…

How great is that line? “I was just talking to George Miller!” Do you realise what a pair of fortunate bastards we are? I mean, seriously. “I was just talking to George Miller…” It’s like saying, “By the way, I saw God during breakfast, and he said I could have the blood sausage and it’s good for my arteries!”

I’ve had quite the morning! But yes, we were talking about how theories spring up around directors’ movies that they didn’t necessarily intend. Has that happened to you?

Yes, but it doesn’t matter. What happens to me is that I always say, “Here’s my movie the way I codify it.” I try to write the movie being mindful of certain things, like I organise certain symbols and things. But there is another layer that you’re completely unaware of, that not only might be different than what you’re trying to organise, but might actually be completely counter to your intentions. That’s because any act of communication – not just art – has a conscious level and a subconscious level. You’re communicating what you think you’re communicating, but there’s also another layer that is profound and you’re not in control.

Are you aware of anything like that on Crimson Peak yet?

I’m sure there are a lot of very disturbing things working there! I may fail, but I always try to find a humanistic streak in anything I try to do. I try to be in favour of the humanity in a strange way, even in the darker things. In Crimson Peak I do the same thing I did on The Devil’s Backbone, which is as the movie progresses, rather than you hating the villains more and more, and cheering when they meet their end, I try to build the villains into becoming more human, and sort of understandable by the end. Even the most horrible historical figure was at one point a kid that was loved by his mother and did cute things. At some point there’s a human origin to everything we experience, and I think it’s important to deal with that.

Tom Hiddleston said that when he first read the script, he cried…

Yeah. He’s a very sensitive man, and he has that vulnerability. I think he’s utterly adorable. If he was caught in an alley grinding puppies, you’d go, “Awww, puppies!” He’s sort of bulletproof adorable.

The relationship in the movie between Tom’s and Jessica Chastain’s characters is extraordinary and deep, and it’s interesting how quickly you cut away from Edith and Thomas to focus on scenes with Thomas and Lucille.

This movie is the one I have tampered and worked with the most in post. That rhymes! That is because I had two choices: I had the choice of doing something where you wonder, “Are they or are they not…” or to do a movie about somebody going into a really wrong relationship. I chose the second route. We previewed the movie twice in much longer cuts. The first preview was 15 minutes longer; the second was about 25 minutes longer. And I tried to make them the wrong cuts to learn the right things. I didn’t want to preview with the cut that I felt was perfect. I saw the reactions and tailored the movie to what it was clear the audience was thinking. I colour-corrected and tampered with the digital cinematography of the movie four or five times more than I did with Pan’s Labyrinth. We mixed the movie about three full mixes, instead of a single mix. I think we had 12 recording sessions. I think we did something like 75 versions of some digital shots. I utilised most of a year to work on the movie. Normally I deliver them in six months if I can. I normally have my director’s cut 12-14 weeks after wrap. On this one my Post Production supervisor kept saying, “Is it locked this time?” We opened three bottles of champagne! They were getting cheaper and cheaper! The final one I think was cider.

Can it be counter-productive, taking that long?

It’s never happened to me. This one needed it, because I wanted it to be a visual world. You can never guarantee that somebody will like a movie. It’s like religion: we all respond to the bells of the church we believe in. You can’t make a movie for everyone. So if you like this movie, I want to give you a world that you can fall into. I want to give you a movie that you can feel was hand-made; that we laboured on it; that if you watch it a second time you can find new layers, and a lot of them are going to be in the visuals. The movie is full of little signs and symbols, and the way we designed the house. We designed a wardrobe so that, instead of just eye-candy, you get eye-protein. There’s content in the visuals. The look of the movie and the content is inevitably the same thing. If you’re deliberate about it and you calculate it and you work on it, it can be eye-protein.

The level of detail on set was extraordinary. The word “fear” was written all through the house, but you never see it on screen.

Mm-hmm, it’s in the furniture; it’s in the woodwork; it’s in the walls and the floor patterns. But it’s not that people are going to read it and become afraid. It’s just playing with things. The furniture and the props existed in two sizes, so that Edith looks smaller when she’s afraid. The movie uses the symbol of moths and butterflies constantly, to symbolise the two main characters who to me are Lucille and Edith. The wardrobe is patterned like butterfly wings, and when Lucille is running her gown opens like the wings of a moth, and so on and so forth. Just colour-coding the movie, I basically used three colours: golden, for the American period; cyan for the European period; and red, which exists only in connection with the clay [around the house], the ghosts and Lucille. Nobody else wears red. You treat it like a painting. When I visit museums with my kids or my wife we always stand in front of a painting, and the painting is always much more interesting if you know the story behind.

How long did it take to design the film?

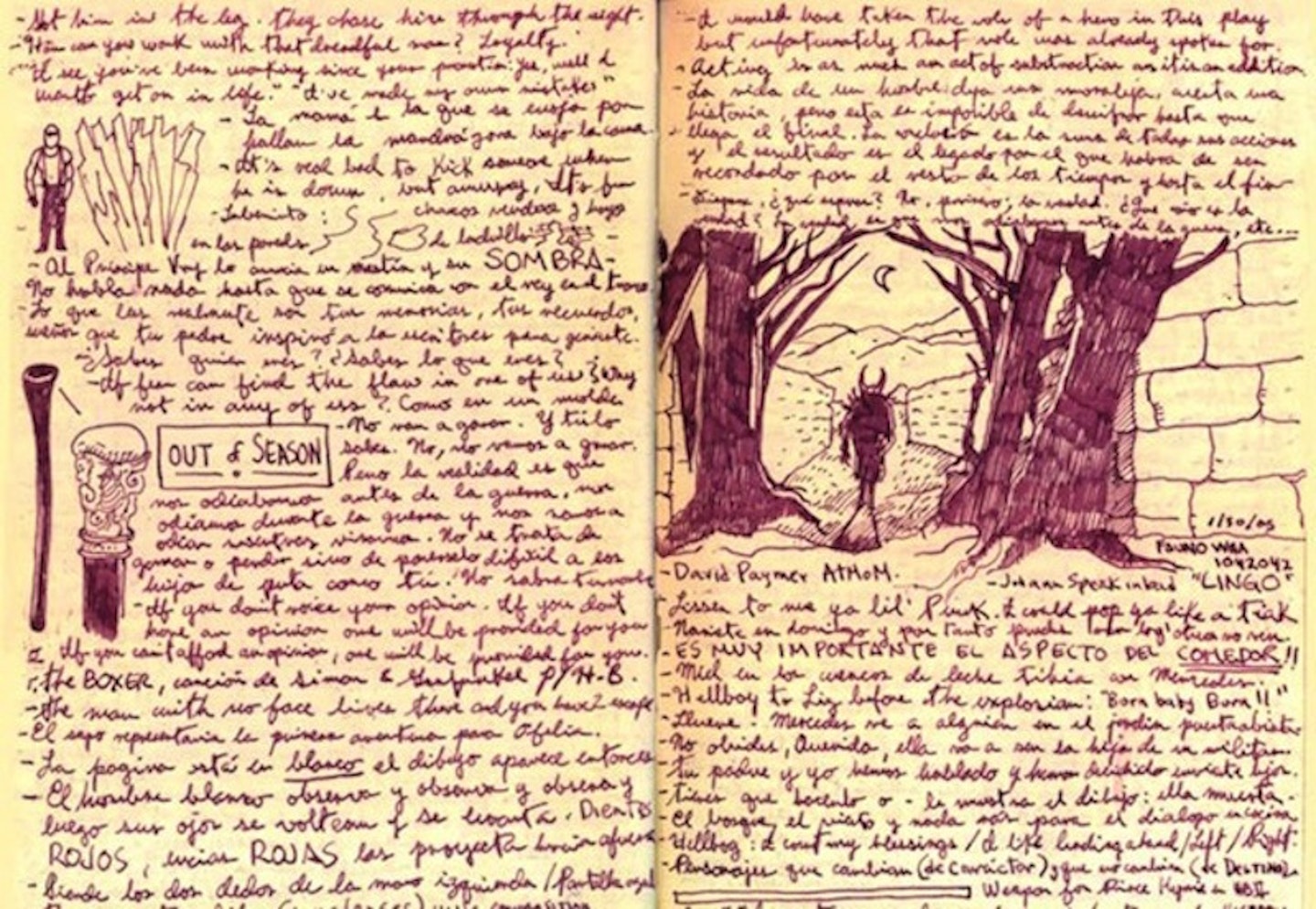

It took a long, long time. I wrote the movie with Matthew Robbins eight or nine years ago. I started doing notes in my notebook back then. Then we started pre-production, and six months before anyone else joined, I rented the apartment across from mine to lodge the designers, so I can see them every day. Then the production designer comes. Then the wardrobe designer comes, and you already have a palette of colours, you already have a proposal of how you see it. I wrote biographies of the characters for the actors, and then gave those same biographies to the set designer and the wardrobe designer, and decide how to tell that biography through the visuals. I’ll give you an example: the house of Edith is all straight lines, even the lines of the wallpaper. It’s a very modern, nouveau-riche, ostentatious house for the turn of the century. The family has been prosperous for 30 years, and you see all that: you see the father dressing very sharp and so on. And then you see Edith’s clothes are the same colour, gold, and she becomes a drop of gold through the whole movie.

Then you see the house of the Sharpes, and the house is full of these gothic arches, and really coruscated, rotting, decaying textures, cool colours. It’s a house that has parts that are medieval, so it’s really a completely different stand on their family history. Then you see their clothes, and they’re very, very tight, like cocoons or shrouds. They are fabricated to be ten years older than anybody else’s wardrobe. They’re wearing their parents clothes. Imagine somebody walks in here with great bell-bottoms and a tie-dye shirt. That’s how shocking their clothes would have been in 1901. They’re not just nice looking clothes: they’re telling you something.

That’s what I had on just before I came in.

Yes exactly, when you interviewed George Miller! And you dropped a little acid…

You’re always very busy; you always have lots of projects sort of bubbling under the surface…

That sounds beautiful! “Lots of projects that are never financed” is a better way of putting it, I would say. From my perspective they’re not bubbling. They’re sitting stale in the corners covered in mould. This one was completely inactive because of $12m. Everybody wanted to do it for 30-35, and I said we needed 48-50, just because I thought the gothic romance needs a bit of an overwrought, melodrama style, and if the actors are acting that tone, which is not naturalistic at all, then the visuals need to have those two notches above reality too. On the other hand I also designed the movie to accommodate a very classically roaming camera: we’re never doing insane moves; it always feels like an old, large camera. So I need to build a house, because I need to have openings for the cranes and the dollies. So the movie lay, in your nice term, bubbling for about eight years, and then Legendary said they’d do it for my number. It’s a hard movie to pitch to a studio. It’s very deliberately female-centric; it’s a genre that no one has really tackled this way in at least 40 years; and it’s R-rated. Legendary initially said we couldn’t have the budget and the R-rating and I’d have to make adjustments, give up 30% of my salary, really stick to the budget. We actually came in $1m under. I gave them change. But I didn’t blink. I told them to of course take the salary, but not to touch the R. And they stood with it.

Why was the R-rating so important?

The core of the movie is very morally ambiguous. You’re not going to come out of the film feeling that the world is right again. There’s a sense of melancholy and loss and gothic that you have to keep in a very adult core. It’s not a fun movie; you’re not going to be throwing popcorn. It’s not a horror movie; it’s a gothic romance. More than scary, it’s eerie and unsettling, so the R was necessary for the violence and the sex.

Wasn’t an R-rating one of the sticking points with At The Mountains Of Madness?

Oh yeah! But now that PG-13 has been pushed [so far] I think that Mountains maybe could be done with a dual cut. Nothing is particularly gory, and I think you can go to more unsettling places [now]. If that came around again I would think about it twice. This one I couldn’t. I couldn’t do it PG-13.

How do you decide what’s next?

I’ve done nine movies, and I have written or co-written 23 screenplays. So there are 14 un-bubbling projects that I have. I’m like the fisherman: the ones that got away are the bigger ones. I have Monte Cristo, which I adore, which is a gothic version of The Count Of Monte Cristo. I have The List Of Seven with Mark Frost, which is a fantastic movie, but I think the Robert Downey Jr. Sherlock Holmes did a lot of what we were trying to do. There’s At The Mountains Of Madness, there’s The Wind In The Willows… There are so many! When people read about them online, all they read is a title and the company that’s making it, and it dies there, and people wonder what happened to it. What happens is I put a year or two years into doing the screenplay – and anyone who has written a screenplay knows how hard it is – and then deal with the heartbreak when it doesn’t get made. Beauty And The Beast at Warners, and The Witches at Warners, are I think two of the better screenplays I’ve ever written, and they didn’t get made. People think directors live in a room full of pillows, smoking a pipe like the Caterpillar in Alice In Wonderland saying, “Let right be done! Let’s tackle At The Mountains Of Madness!” But the truth is you don’t have the choice. You don’t live in a lofty place. You’re struggling to get the movies made, but you cannot finance them.

It’s obviously outside your control for the most part, unless you go micro-budget.

Which I’ve done! Right now I’m going to go to a much smaller budget, in between Crimson and if Pacific Rim 2 happens, which I hope it does. I’m going to a smaller budget to come out of the water and take a deep breath. Economical constrictions are great if they come with freedom.

So what can you tell us about the next project? Time-wise if not about the project itself…

I think we will be shooting in May or June next year. I’m writing, we’re prepping at the same time, we’ve been doing research and development on it for a while. So knock on wood… It’s English-language but might as well be Spanish! I’ve been working on it for five years. It was always waiting in the wings. That one was bubbling!

And what about Pacific Rim 2?

The reality is that Pacific Rim 2 needs to be tackled with very, very tight budgeting. It needs to be really big but done for a number that makes sense and fits the $411m that the first one made. They want to match the ambition with very careful pre-planning, so hopefully it’ll happen. We’ve finished the screenplay, and we did a new budget that took us on several scouts to different countries until we found exactly what we needed to build this or that. Then the people that are way above my pay grade decide if they’ll do the movie or not. It’s not my decision. It’s the same with Hellboy 3. I would do Hellboy 3 in a second. I actually think the studios should see that there is an audience for it. But I don’t run a studio. If I did I’d probably take a billionaire studio and make it a millionaire studio in three easy moves.

We had Ron Perlman on the podcast about a month ago and he was talking about Hellboy 3…

Of course he was! The last time I had any discussion about Hellboy 3 in Hollywood, was with Ron Perlman on Ventura Boulevard in a Coffee Bean shop. He was having a latte and I was having a glass of water. I think it should be done. I don’t know how these decisions get made, honestly. I’ve been in this business for 20 years, and how movies happen still eludes me. I guess if you make something that makes a billion dollars you get some leeway.

That’s the interesting thing about Pacific Rim, which is on that threshold of sequel-or-not-sequel.

It was huge in terms of it not being a property. It didn’t come from comic books, toys, pre-existing material. We created it all. So if you compare it with many of the first of a trilogy, the Wolverines or even the first Batman of the new series, we did really good. But the key was, can we do it for less but make it the same size and scope? And the answer, after trial and error and learning, is that we can go at it in a way that’s more fiscally conservative and still deliver. Living inside the business is different than looking at it even remotely as an entity that has one line of operation. It really is like a billiards shot. There’s not one single factor, not even dollars, that determines things. It’s like an existential billiard ball. You have an actor that wants to do it, and that actor is or isn’t hot, and that determines another vector. The Hellboy films did X number at the box office, but they did huge numbers on Blu-ray and DVD. Hellboy 2 didn’t happen because an executive said, “I like Hellboy 1!” It made sense financially. There are so many vectors, and some of them are so random that you would shudder. After 20 years I’m still puzzled.

Is there a sense that you’re making up for lost time after The Hobbit?

Not really. I think that planning a lot of The Hobbit was great preparation, for example, to be able to execute Pacific Rim. I was already handling [similar] logistics when we were prepping The Hobbit. Everything makes you grow, and my two years in New Zealand remain two of the best years I’ve ever had in my life. So I’m very grateful.

And now you’ve joined Twitter…

Yeah I did! It’s because there were other guys on Twitter saying they were me, which is puzzling. I don’t want to be me! And somebody else wanted to be me. They were saying they were me. They were saying, “I’m on a tour with a book,” or “Today I showed a movie,” and I just felt that it was troublesome. We kept shutting them down. One of them was doing much better than I’m doing! One of them had about 180,000 followers. I should have kept that one. But I thought I’d do it, and the only thing I want to do there is tweet things I love. I don’t want to tweet against. I want to tweet in favour of. The more you put out in the world your enthusiasms, and the things you’re happy that they exist, the world is a little better. Sturgeon’s law says 90% of everything is shit. Del Toro’s law says 10% of everything is great. Let’s talk about that 10%.