Concluding the trilogy started with Alice in the Cities and The Wrong Movement, this is the heir to such road movies as Easy Rider and Two-Lane Blacktop, as its characters make as much psychological and spiritual progress as they do territorial. However, in embracing such a quintessentially American genre, Wim Wenders found himself trapped between his themes and his style. Indeed, such is his reliance on references to US culture that it becomes impossible to gauge Wenders's precise stance.

A key idea is his lament for the declining German film industry, whose miring between pulp and porn is movingly depicted by the state of the delapidated venues the twosome visit along the Zonenrandgebiet. But Robby Müller's sharply etched monochrome imagery owed more to the Depression photographs of Walker Evans than any Germanic art precedent. Similarly, the use of rock`n'roll on the soundtrack and the throwaway citations of such ephemera as posters, clothing and junk food all emphasised the fact that the Federal Republic had become a Cold War colony of the States in the same way that the Democratic regime across the border was in thrall to Moscow.

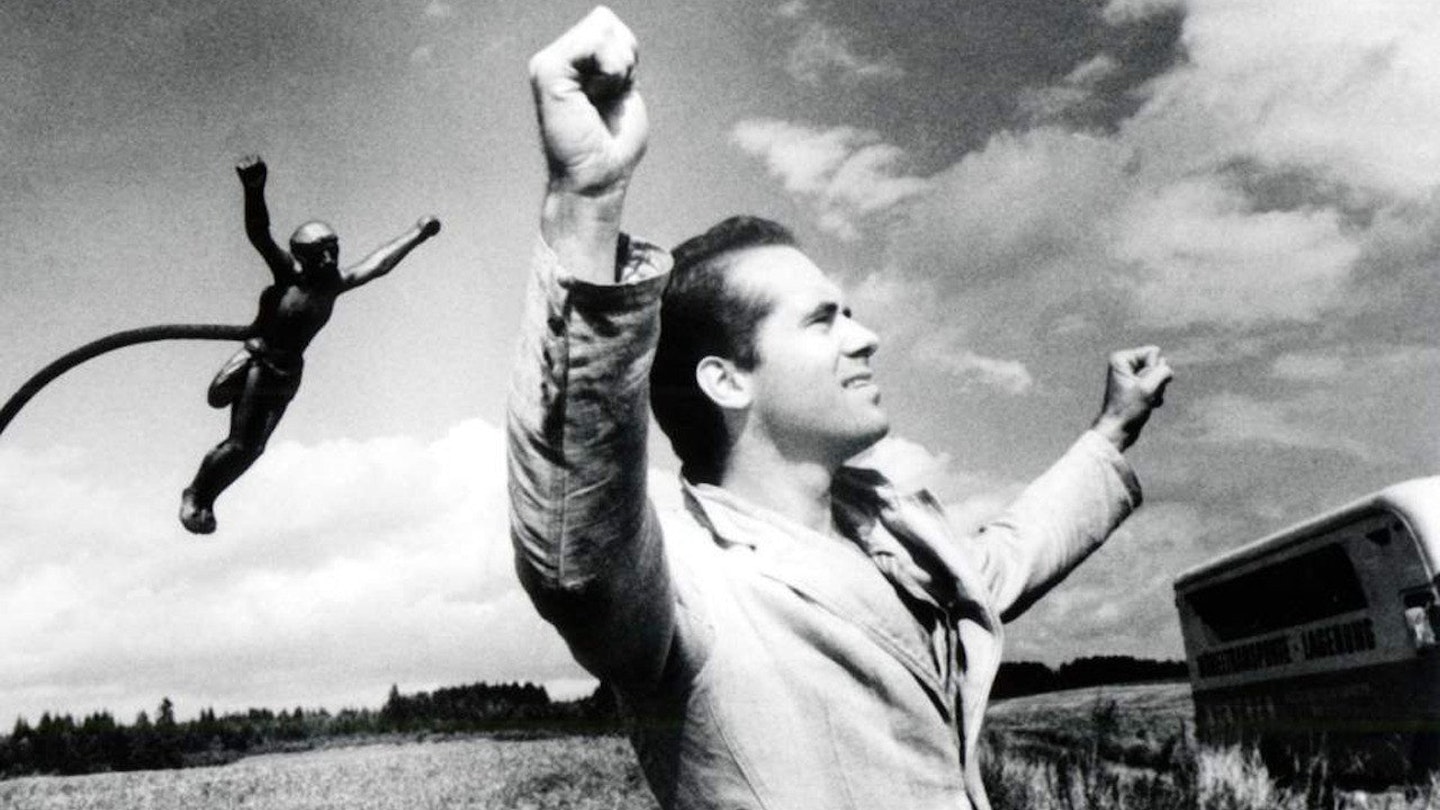

Yet, while he pays tribute to such Hollywood features as Nicholas Ray's The Lusty Men (1952), Wenders also reveals his debts to Yasujiro Ozu and the French New Wave. The length and pacing of Kings of the Road was as much designed to demarcate it from the mainstream as the depiction of everyday events that other film-makers eliminated through ellipsis. But by keeping conversation to a minimum and eschewing reaction shots in favour of detaching long shots, Wenders forces us to identify with the unlikely buddies and their relationship to the passing landscape, which virtually becomes a character in itself (something that Wenders hoped would happen, as he shot chronologically and Vogler and Fischler improvised spontaneous responses to the locations along a strictly prescribed route).

The film ends on a vaguely optimistic note. But even then, Wenders suggests that Robert and Bruno have only recognised the need for change rather than identified the means to exact it.