Mistakenly believed to be Ken Loach’s last film, Jimmy’s Hall is more of a consolidation of his favourite themes —the political versus the personal, class, property, outsized flat caps — than a summation or development. A spiritual sequel to 2006’s The Wind That Shakes The Barley, it takes a smaller focus than The Wind... — the ideological swirl surrounding a community hall — and delivers a familiar, engaging, if never ultimately blistering slice of rarely told Irish history. His 11th collaboration with screenwriter Paul Laverty, Loach imbues the story of Jimmy Gralton’s (Barry Ward) simple village hall — viewed as a hotbed of political and religious dissent by the local landowners and clergy — with interesting dynamics, between atheism and religion, communism and property owners and the Americanisation of Irish values. Around the central struggle, Loach also serves up Seamus Heaney-esque bog business, and a tentative relationship between Jimmy and long-lost love Oonagh (Simone Kirby), reaching its zenith in a beautifully constructed dance.

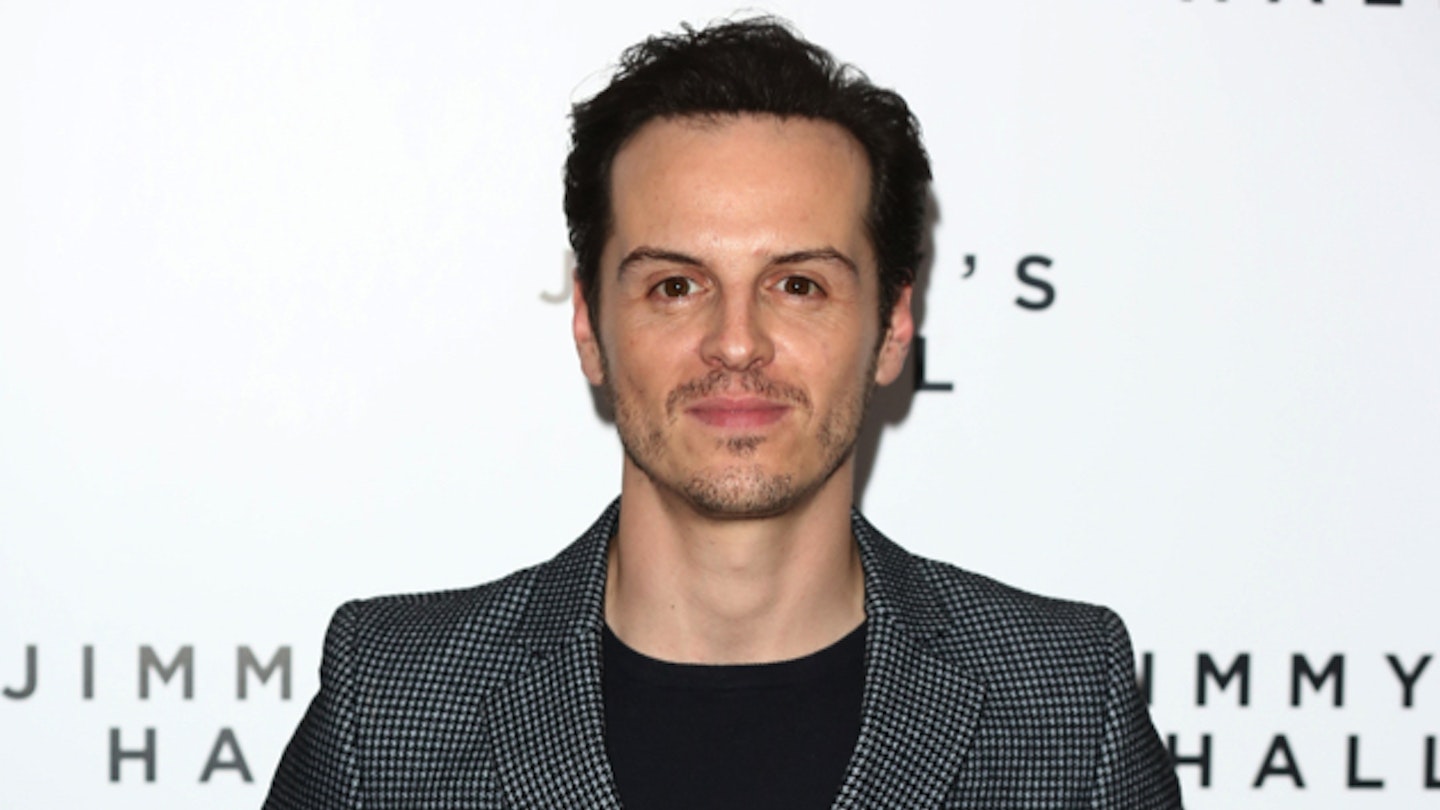

Yet, the whole thing isn’t as passionate and gripping as you’d expect. Ward’s Jimmy is charismatic enough, but he doesn’t have the shades to make him real. Kirby’s Oonagh is equally under-nourished and the Catholic church — Jim Norton’s fire-and-brimstone Father and Andrew Scott’s more progressive understudy — seem to represent positions rather than three-dimensional people. The film evinces a nice sense of culture coalescing a community — there’s a lovely jazz-dance lesson set-piece — and the production values feel authentic. But what’s missing is anger, bite and complexities. Its final moments are strangely similar to Mona Lisa Smile. Who’d have thought a Ken Loach film would end on the same note as a Julia Roberts vehicle?