There is a moment in Gareth Edwards’ Godzilla in which two creatures — M.U.T.O.s in the film’s parlance — start nuzzling. Given the director’s startling lo-fi debut Monsters gave us full-on creature rutting, you might fear that this is a daring director being shackled by a rating-conscious studio. Happily, the Brit director’s take on the Toho studio icon gives full reign to his ability to create compelling imagery and a knockout monster mash. It’s a shame, then, that the movie gets caught between honouring the character’s B-movie conceit AND delivering a let’s-take-everything-super-seriously approach de rigueur in post-Dark Knight blockbusterdom. If any film needed a sense of levity, it is one about a 355-foot lizard hitting stuff.

The movie gets off to a cracking start, a title sequence depicting nuclear tests, Darwinian theory, sea monster illustrations and redacted information all to Alexandre Desplat’s flash-and-thunder score. Yet, unlike 99.9 per cent of recent blockbusters, the film then admirably slows down to set up story strands of (chillingly mounted) family tragedy, anomalous seismic activity, frustrated interrogations, perplexed scientists and all-round conspiracy.

The models here seem to be Jurassic Park and particularly Close Encounters (look out for the gas masks bit) as the film flits between personal tales — bomb disposal officer Ford Brody (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) helps his father Joe (Bryan Cranston) investigate what really happened at the Janjira nuclear plant — and a global overview, in which scientists (Ken Watanabe, Sally Hawkins) team up with the military (David Strathairn) to try and make sense of it all.

Edwards and credited writer Max Borenstein try their darnedest to legitimise the potentially hokey conceit, smartly respecting the creature’s atomic age roots by imagining the ’50s nuclear tests as attempts to kill off the subterranean creatures and peppering the movie with post-War On Terrorism reference points: jets plummeting out of the sky, carnage playing out on 24-hour rolling news, helicopter shots of refugees escaping to safety, the displaced seeking out loved ones in huge stadia. There is definitely no place for Godzooky in this world.

Yet underneath the patina of realism, Godzilla doesn’t have the story smarts to pull you through. Much of the drama set up in the first 30 minutes bears little consequence later on. The scene work suffers from logic lapses (where does Watanabe get his preternatural understanding of Godzilla’s motives?) or feels just plain fudged — a plan involving a nuclear bomb is unclear and unthrilling.

Edwards creates evocative moments, both small — a slug crawls over a toy tank — and huge — a submarine dangles from a tree — but he has less of a sense of keying it into a narrative imperative. The HALO jumping that everyone loved in the trailer remains fantastic but makes little sense when it appears the army can simply drive into the danger zone. If the movie had a different, more playful tone — Independence Day, for example — all this would be less problematic. But in the credible real world the film seems to want to set up, it just rings dumb.

While the characters may get time to breathe, they don’t emerge as a complex, memorable bunch. For all the great casting, the first-base writing never allows these people to emerge as anything but stock characters. Bryan Cranston is at his most Cranstonish as a man trying to prove a theory deemed crackpot, Aaron Taylor-Johnson is a colourless, stoic soldier, a criminally under-utilised Elizabeth Olsen is a wife-mother-nurse permanently stuck on the end of a phone, Ken Watanabe is a noble Japanese scientist who spurts homilies about messing with nature, Sally Hawkins his exposition-clarifying assistant, and David Strathairn labours as a one-note military man. Given, as with most creature features, the humans are bystanders doing practically zilch to affect the outcome, it demanded a more rounded, engaging dramatis personae.

This lack of personality extends to the main monster. In certain respects the Lizard King struggles to register as the star of his own film. Not only does Edwards afford the evil M.U.T.O.s (Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Objects) a better introduction — Godzilla’s entrance feels a bit thrown away — the malevolent, moth-like creatures also seem to get longer screen time and more characterful business.

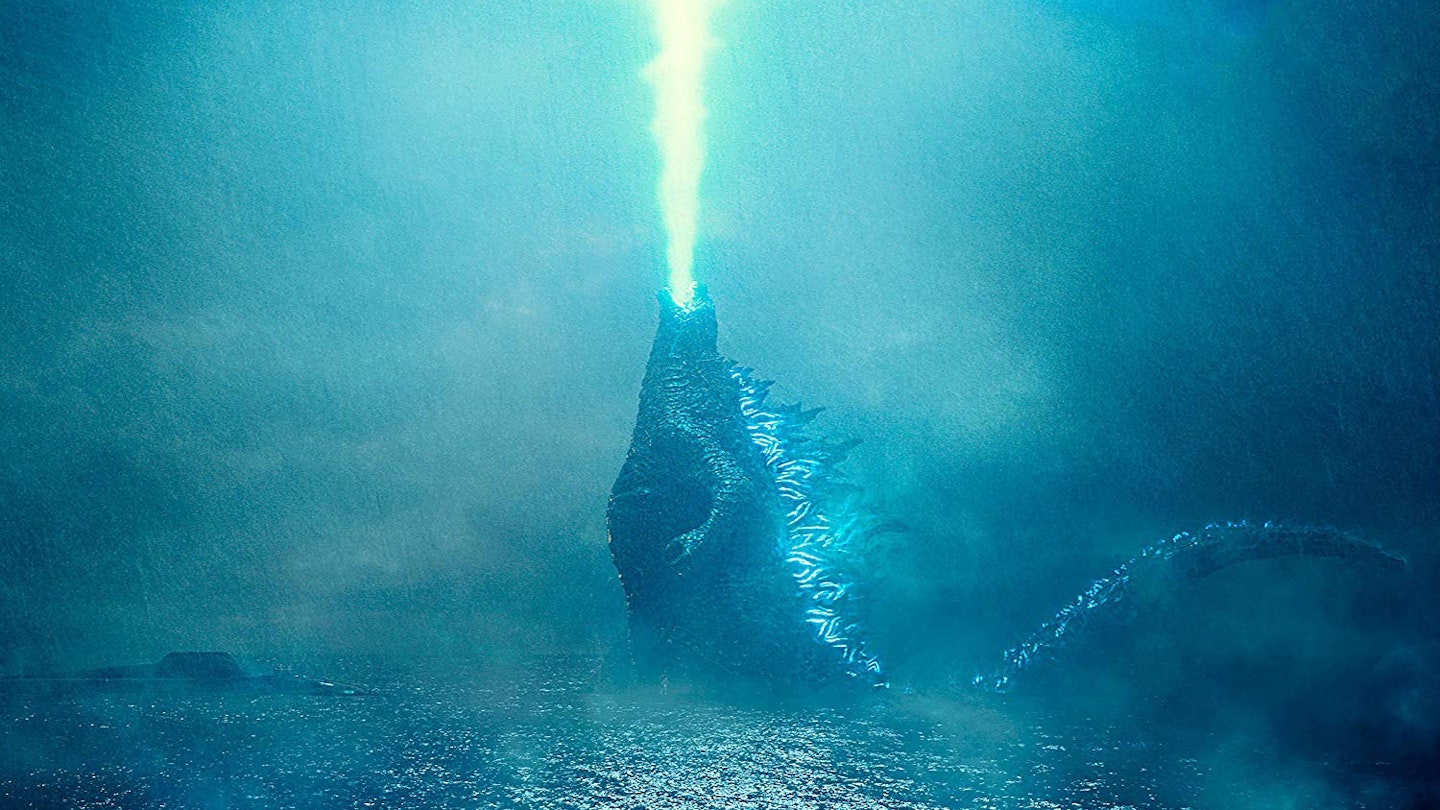

As you’d expect, Edwards excels in creating awesome kaiju juju — be it toppling aircraft like dominoes or Godzilla swimming under a battleship — that always leaves you wanting more until the battle for San Francisco delivers on the promise. This is not the men-in-suits wrestling we’ve seen before; instead it’s a beautifully shot (very Apocalypse Now-y) and choreographed smackdown that, for once, doesn’t feel like a bunch of pixels hitting each other. It somehow combines the richness and charm of a ’50s George Pal flick with the believability modern technology affords. If the rest of the film could have pulled off the same trick, it would be the Godzilla of our dreams.