“I can’t remember a time when you weren’t in my life," cracks Sigourney Weaver's Ripley to her old monster adversary in David Fincher's Alien 3. Indeed, this particular monster and this particular character are now so familiar that it is hard to remember a time before Alien came out, introducing not only Weaver, previously micro-glimpsed in Annie Hall, but also the bio-mechanical steel-fanged alien itself. On the film's original release in 1979, science fiction buffs complained that they had seen everything here before - citing It!, The Terror From Beyond Space, Night Of The Blood Beast and Planet Of The Vampires - but that was entirely beside the point. Alien was "just" a haunted house movie in space, with a bunch of foolhardy souls wandering into dark places to be leaped upon by a Flying Purple People Eater, but the old cod had never been served with quite this much relish. As with Star Wars, the point here was not that Alien was a science fiction movie, but that it was a science fiction movie that was seen by people who don't usually go to see science fiction movies.

Alien was The Rolling Stones to Star Wars' Beatles.

Co-producer/co-screenwriter David Giler has remarked that Alien was The Rolling Stones to Star Wars' Beatles. Two years earlier, George Lucas had taken an indecently ancient Flash Gordon plot and thrown in outer space effects which had never been seen before. With Alien, the magic had worn thin and Ridley Scott now showed the downside of this heroic Star Wars universe. While Luke Skywalker and Han Solo are swashbuckling in some other part of the galaxy, Alien's dilapidated spaceship is unglamorously hauling freight for a corrupt corporation. Much of the dialogue has people bitching about how little they get paid and complaining that their tools aren't right for the job. It's almost as if the stereotypical British workman had been exported to the farthest reaches of the universe.

In the classic horror movie tradition, Alien establishes a realistic backdrop, then introduces its monster. The two best-remembered moments involve John Hurt and the face-hugger that spits out of the alien egg and attaches itself to his helmet and, most stomach-distressingly, the chest-burster -- aptly described as a penis with teeth – which emerges bloodily from his insides just as the story seems to be taking a break. Preying on this universal fear of having a monster squelch the soft, vulnerable parts of your body, these scenes take the mutations of David Cronenberg's early work on Shivers and Rabid and reduce them to effective cheap shocks. Along with the hand-from-the-grave at the end of Carrie and the killer's leaps from the dark in Halloween, these are the scariest things in 70s cinema, knee-jerk jolts which combine pie-in your-face shock with a deep dread of those disgusting things lurking inside your body just waiting to burst out.

These punch-lines come surprisingly early in Alien and, especially decades on, the rest of the movie is something of a letdown as the full-grown monster stalks and splats the remainder of the crew. The third great scene doesn't even feature the alien, however, coming when Ripley socks Ian Holm on the jaw and his head comes off in a gush of white blood revealing him to be an emotionless robot. Weaver, following 70s movie heroines such as Genevieve Bujold in Coma and Jamie Lee Curtis in Halloween, bests the beast, while all around her a bunch of useless men die screaming.

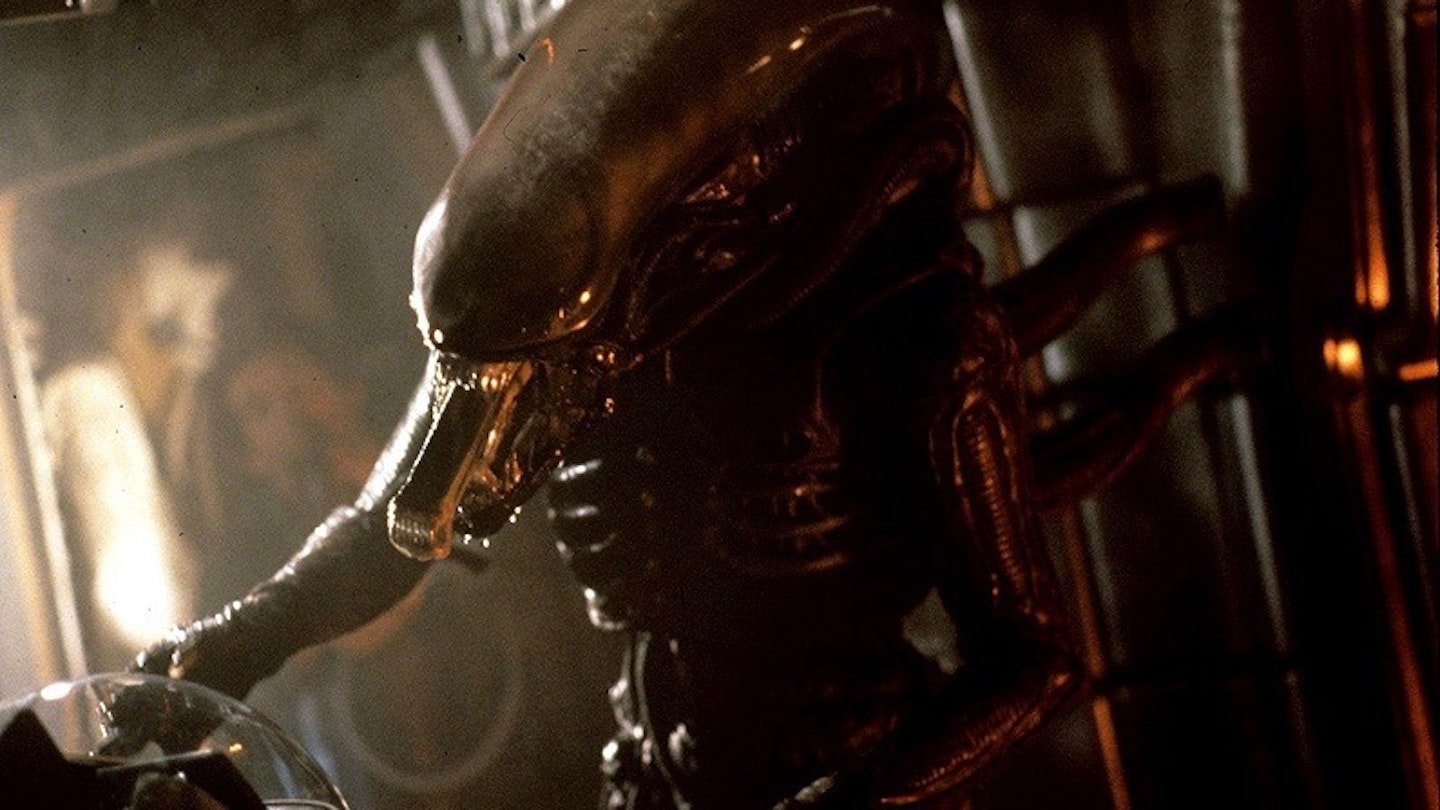

What keeps the film working so well is Scott's policy of allowing significant glimpses of the monster while never quite letting it out of the shadows. Drawing from the elaborately obscene and intriguing paintings of Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger, Alien recalls those old "how many animals are hidden in this picture" puzzles, but with sexual organs worked weirdly into the design of the organism and its environment, from the vaginal openings of the spaceship and the eggs to the penile head of the monster, with its erectile teeth. Covered in glistening sex-slime and lunging out of the darkness at a half-dressed Sigourney, this monster is clearly the worst imaginable blind date. The disgust with sex and childbirth seeping through the movies, where penetration is rape, and birth entails the death of the mother, perhaps accounts for Ripley's failure to consummate suggested romantic relationships with Tom Skerritt in Alien and Michael Biehn in Aliens.

The Alien series is more than just a series of films.

If Alien is a horror movie, then Aliens, its 1986 sequel ("This time it's war") is a combat movie. There is less disgust, more urgency; less fear, more genuine excitement. Director James Cameron is clearly not as taken as Scott with the foggy prettiness of it all, expanding the envelope from a game of deadly touch tag with just one monster to a mass battle with dozens. Aliens, especially in its "director's cut" version, is a bigger film than Alien in its added spectacle but also in its breadth of character. In Alien, Ripley became the heroine by default because she happened to outlive the rest of the cast; in Aliens, perhaps because a no-longer unknown Weaver had a say in how she was written, she is demonstrably fitter to survive than the more skilled soldiers, balancing her willingness to fight and die with a genuine human warmth, as demonstrated in her scenes with Newt, the blank-faced little girl who is so callously and clumsily killed off in the first minutes of Alien 3. In Alien, the robot alleges that the alien is most suited to survive, but Aliens demonstrates that Ripley, the believe-it or-not representative of common humanity, is after all more competent to settle the universe than a chitinous hive organism.

The Alien series is, then, more than just a series of films. From the rumoured existence of a longer cut of Alien - including scenes which feature in Alan Dean Foster's novelisation of the script but which didn't make it to the cinemas - through the eventual issue of a restored Aliens to the flurry of phantom preproduction versions of Alien 3, they have each seemed to spill out beyond their frames, encouraged by the co-opting of spin-offs such as comic books and novels into the mythos. In the end, the Alien phenomenon is one big scary story, with one big scary universe behind it.

This article first appeared in Empire magazine, issue #39 (September 1992).