Twenty-seven year-old Pier Paolo Pasolini was already a published poet by the time he arrived in Rome in 1949 as a gay, Marxist country boy whose poverty quickly reduced him to a criminous association with the ragazzi or slum punks with whom he identified and from whom he would continue to purchase sexual favours until he was murdered by one in 1975.

In addition to participating in a gas station robbery, Pasolini also helped a bandit escape from the police and he had achieved a certain notoriety before he published his first novel, Ragazzi di Vita, in 1955. Fending off a charge of obscenity, he followed this with Una Vita Violenta (1959), which served as the basis for Accatone.

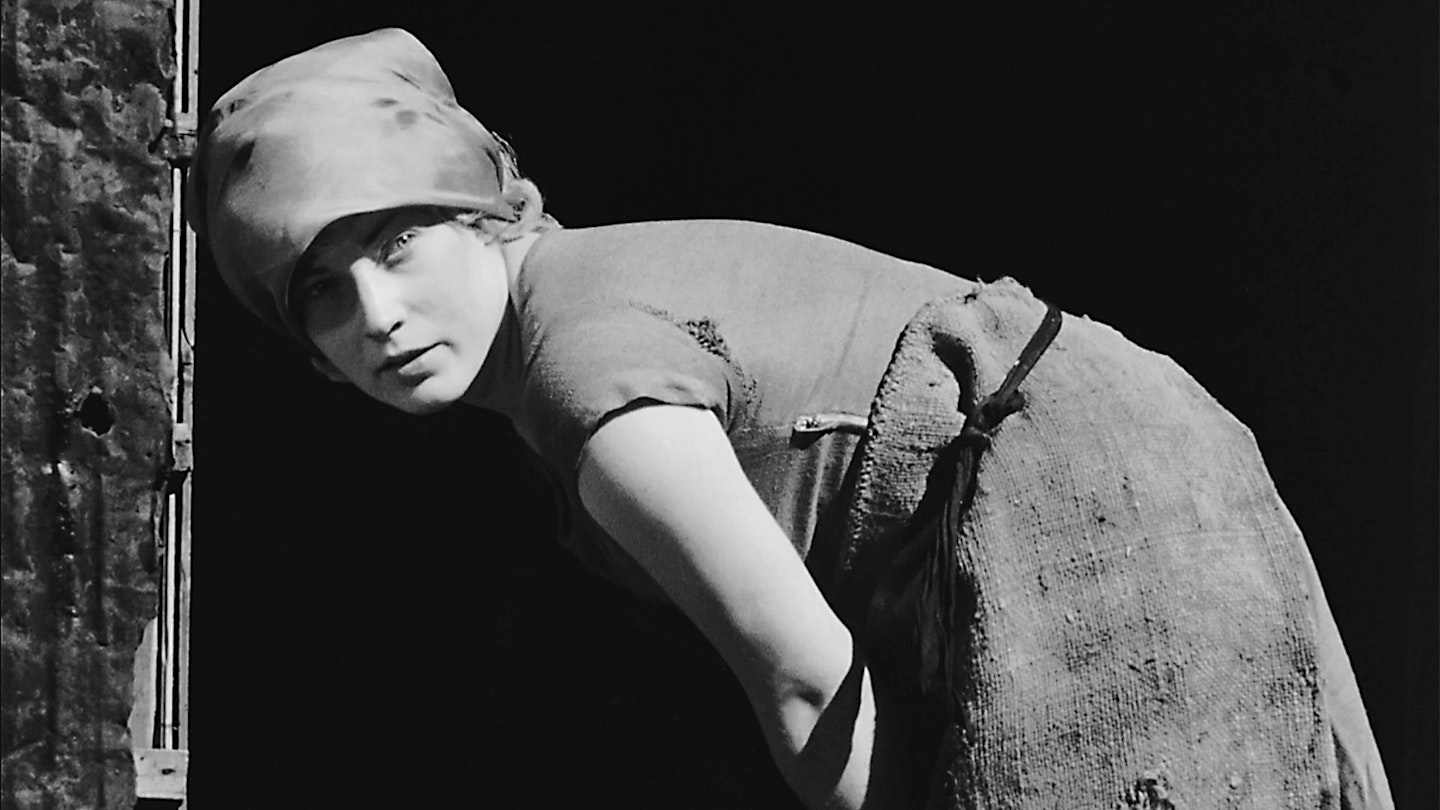

Having started screenwriting in 1954, Pasolini hoped to use his contacts to fund the film. But Federico Fellini withdrew his support when he saw some test footage, which bore a naive resemblance to Carl Theodore Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (1927).

However, another previous collaborator, Mauro Bolognini, was more impressed and he persuaded Alfredo Bini to produce and Sergio Citti not only to co-script, but also to enlist his brother, Franco, for the title role.

Bernardo Bertolucci, who served as an assistant director, claimed that Pasolini was more influenced by Renaissance painting than cinema in seeking `an absolute simplicity of expression'. Yet several critics have proclaimed that Pasolini's intuitive artistic sensibilities shaped the iconic, if anti-heroic Accatone's squalid pilgrimage around a city of seemingly redundant religious reliquery to the strains of Bach's St Matthew's Passion. However, traces of René Clair, Jean Renoir, Vittorio De Sica and Roberto Rossellini can be detected both in the occasionally sentimental humanism, its use of authentic locations and non-professional players and in the unsophisticated style, whose raw realism was to remain a feature of Pasolini's cinema.